Project Mercury: The History and Legacy of Americas First Human Spaceflight Program

By Charles River Editors

Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors provides superior editing and original writing services in the digital publishing industry, with the expertise to create digital content for publishers across a vast range of subject matter. In addition to providing original digital content for third party publishers, we also republish civilizations greatest literary works, bringing them to new generations of readers via ebooks.

Sign up here to receive updates about free books as we publish them, and visit Our Kindle Author Page to browse todays free promotions and our most recently published Kindle titles.

Introduction

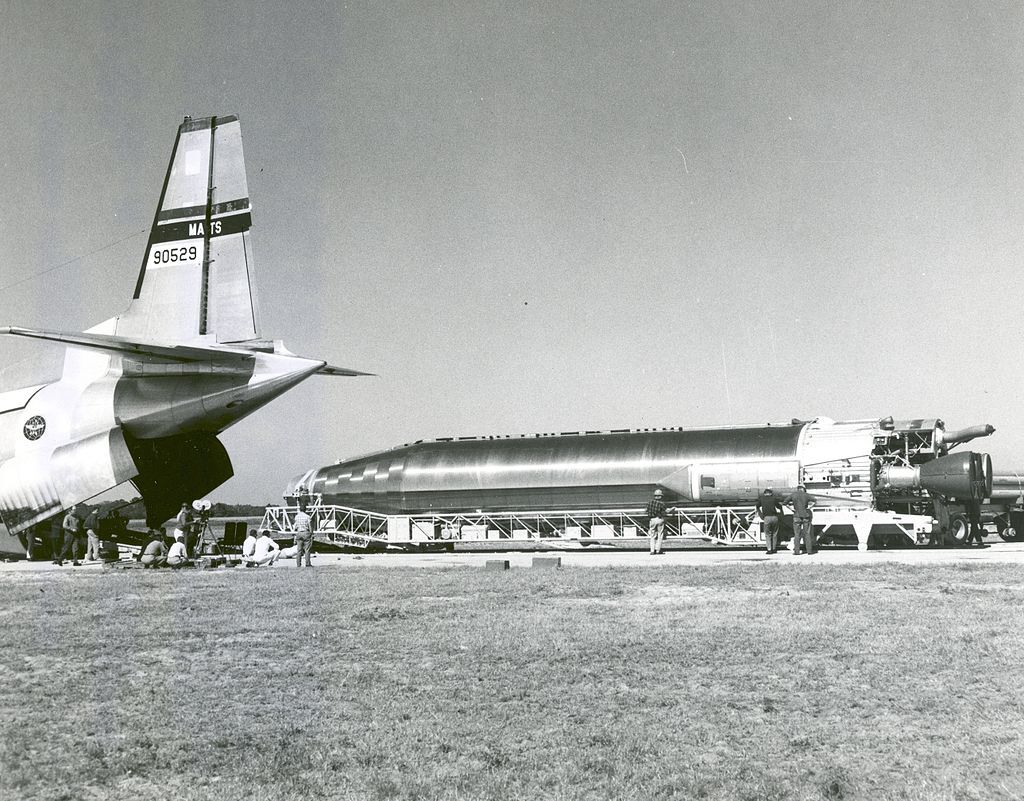

An Atlas rocket at Cape Canaveral

Project Mercury

We're not up there in space just to joyride around. We're up there to do things that are of value to everybody right here on Earth. John Glenn

Today the Space Race is widely viewed poignantly and fondly as a race to the Moon that culminated with Apollo 11 winning the Race for the United States. In fact, it encompassed a much broader range of competition between the Soviet Union and the United States that affected everything from military technology to successfully launching satellites that could land on Mars or orbit other planets in the Solar System. Moreover, the notion that America won the Space Race at the end of the 1960s overlooks just how competitive the Space Race actually was in launching people into orbit, as well as the major contributions the Space Race influenced in leading to todays International Space Station and continued space exploration.

The successful Apollo 11 mission was certainly an astonishing technological triumph, but what is less well remembered now are that many programs preceded Apollo and were essential to its success. Project Mercury was one of those, and in many ways it represented the greatest step forward in terms of the conquest of space. Before Project Mercury, there was no certainty that a human could survive the rigors of a space launch or live outside Earths atmosphere. There was no agreement on just what an astronaut should be, and various individuals involved debated whether they should be pilots, technicians, scientists, or even merely observers in an automated craft. Before Project Mercury, no one was entirely certain what a rocket capable of taking a person into space would look like, or even whether building such a craft was within the capabilities of engineering in the 1950s.

Put simply, Project Mercury aimed to answer these and other questions while overcoming technological and human problems never before faced. All the while, the program took place against he backdrop of intense competition between the Soviets and the United States to be the first to be able to send people into space and, if possible, to use that for military advantage. Because of this, Project Mercury was not just a step into the unknown, but part of an ongoing battle taking place in the glare of constant publicity to allow America to catch up with what frequently looked like an unassailable lead in space by the USSR.

Project Mercury lasted for less than five years, but the missions were some of the most momentous and intense years in the history of space flight. When Project Mercury began in October 1958, no person had traveled to space and some people still believed that this was impossible. By the time that it ended in June 1963, the Apollo Program that would place an American on the Moon in 1969 had begun, but without Project Mercury, there could have been no Apollo Program.

Project Mercury: The History and Legacy of Americas First Human Spaceflight Program examines the origins behind the missions, the people and spacecraft involved, and the historic results. Along with pictures of important people, places, and events, you will learn about Mercury like never before.

The Start of the Space Race

By the late 1950s, what was previously a race to deliver nuclear arms using space became a race for admission into space alone. Although the 1940s and early 1950s were necessarily dominated by a quest to create rockets for military use, the latter half of the 1950s saw the science and technology fueling the Space Race being advanced as part of a competition for political prestige between the two ideological adversaries.

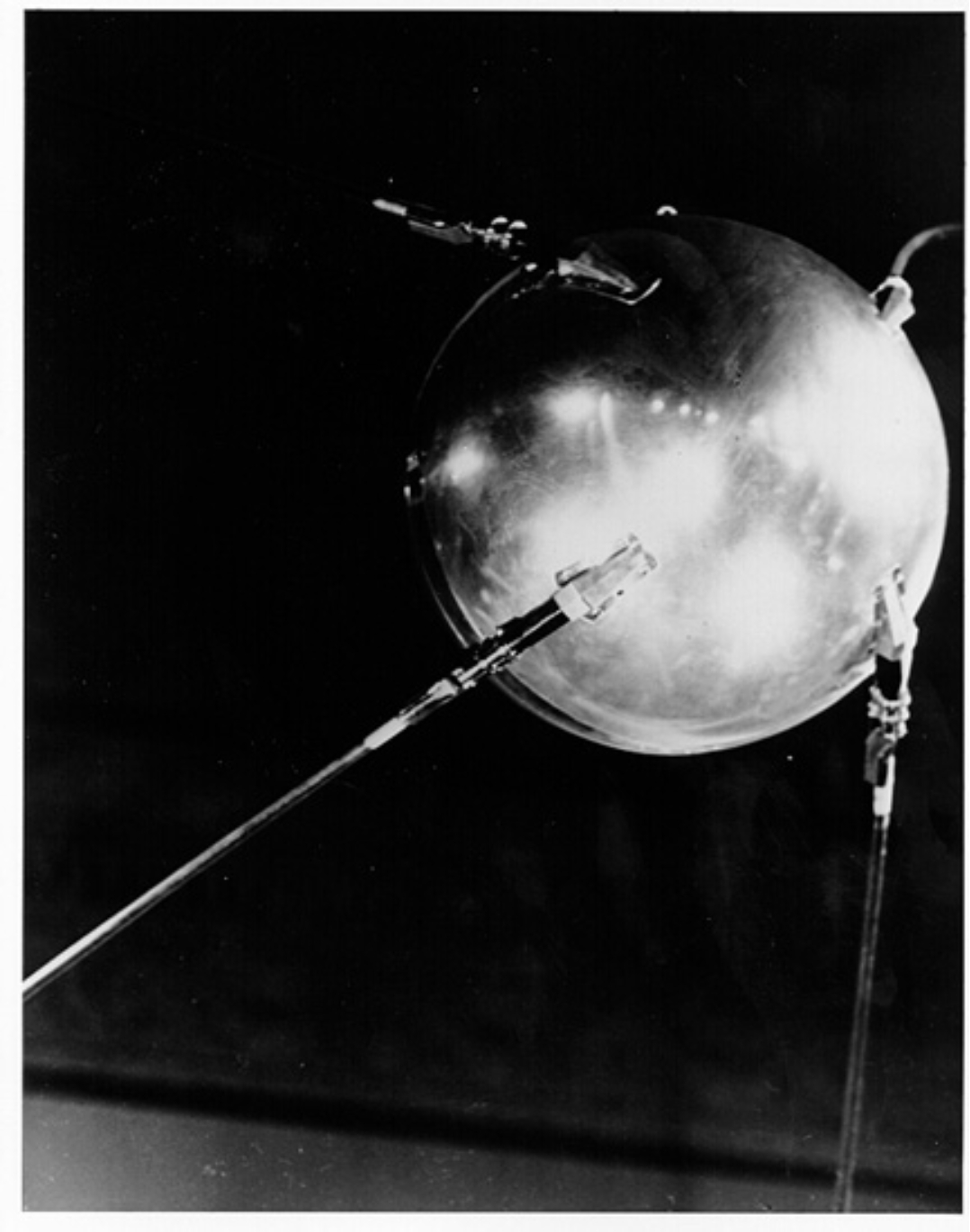

Dovetailing off their success with intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), the Soviets were the first to make enormous advances in actual space exploration. On the night of October 4, 1957, the Soviets prepared to launch Object D atop one of its R-7 rockets. As the worlds first ICBMs, R-7 rockets were built primarily to carry nuclear warheads, but Object D was a far different payload. Object D and the R-7 rocket launched from a hastily constructed launch pad, and within minutes it entered orbit. It took that object, now more famously known as Sputnik-1, about 90 minutes to complete its orbit around the Earth, speeding along at 18,000 miles per hour while transmitting a distinct beeping noise by radio.

Sputnik-1

Thanks to its transmission, and the bright mark it created in nighttime skies across the world, the world was already aware of the launch and orbit of Sputnik-1 before the Soviets formally announced the successful launch and orbit of their satellite. Naturally, the West wasnt thrilled to learn about the Soviets launch of the first artificial object into Earths orbit. Sputnik-1 could be measured in inches, but that large rocket it was attached to could wreak havoc if equipped with a nuclear warhead. Moreover, if Americans could see Sputnik-1, they were justifiably worried Sputnik-1 could see them.

The launch of Sputnik I is largely hailed as the opening moment of the true Space Race, in part because of the fame and fear inspired by the launch, but also because its purpose was not entirely one of military value. While the Sputnik satellite indicated the Soviets had significant military advantages in potentially weaponizing space, Sputniks value was not exclusively military. Internationally, the political reaction to the Sputnik launch was muted. President Eisenhower's White House was largely dismissive of the success, refusing to acknowledge its significance. Eisenhower played down the satellite, saying it was no surprise.

In truth, President Eisenhower immediately realized the implications posed by the Soviets successful launch, and Sputnik-1 was a huge propaganda victory for the Soviets, who could boast not only of accomplishing the historic first but of getting ahead of the Americans in the Space Race. Had something like Sputnik-1 been Americas goal in 1957, it very likely could have accomplished this important first. Wernher von Braun, a former Nazi scientist who became instrumental in Americas space efforts, had successfully designed the Jupiter-C rocket by 1956, which could have allowed the United States to launch a satellite like Sputnik-1 into space a year before the Soviets did. At the time, however, the technology was being designed for use as missiles. In response to Sputnik-1, Eisenhower quickly ordered an attempt to put a satellite in orbit, so a Space Race of a more civilian nature was launched.