Marion Dolan

Deerfield Beach, FL, USA

Springer Praxis Books

ISSN 2626-8760 e-ISSN 2626-8779

Popular Astronomy

ISBN 978-3-030-76510-1 e-ISBN 978-3-030-76511-8

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76511-8

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

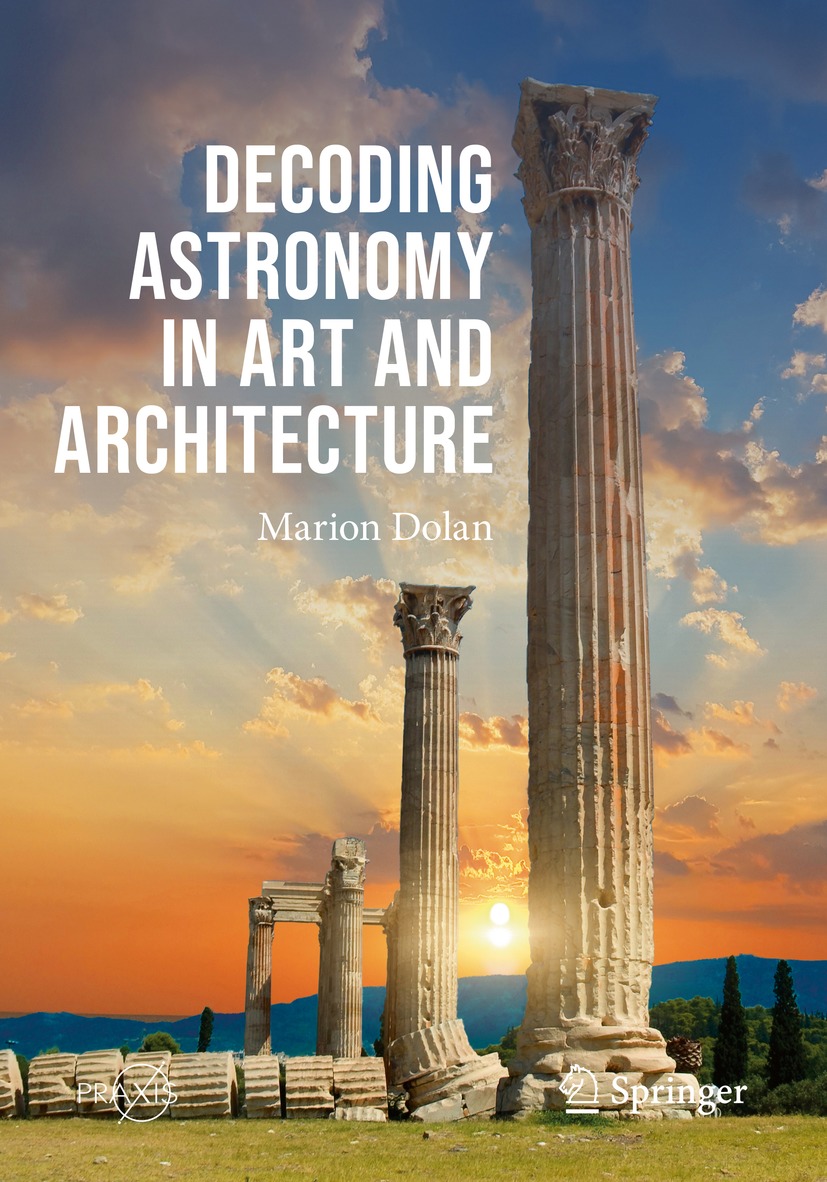

Preface

The awe-inspiring presence of the sky has left a profound imprint on human culture at all times and in all places, to an extent that is seldom appreciated today. It is only very recently that we have managed to construct an environmental cocoon around ourselves.

David Pankenier

The seeds of this book were planted long, long ago after I first read about the extraordinary astronomical event that occurred twice a year in ancient Egypt within the great Rameses II Temple at Abu Simbel. I learned with great interest that an ancient Egyptian temple, carved into the mountainside in the thirteenth century BCE, had been designed to direct a beam of light to penetrate through the entire length of the interior, able to reach the innermost chamber. Inside the cavernous temple, the solar rays on two particular dates illuminated the statues of Rameses and two Egyptian gods, Amun Ra and Ra-Horakhty, enthroned in the innermost chamber. Even more remarkably, the designers positioned the god of the underworld Ptah sitting aside them so that this god remained in the darkness of the netherworld. What a remarkable feat! Upon learning of that initial instance of deliberate light and shadow manipulation, my search began. Hunting for other examples of similar phenomena devised to direct or capture sunlight for particular effects resulted in many more findings.

Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain, England, was my next fascination, then Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth Mounds in Ireland, then the celestially aligned cities of the ancient Maya and similarly orientated sites throughout the ancient world. My fascination with archaeoastronomy continued into the textual transmission of astronomical knowledge through time, and then to architectural designs of temples and churches to manipulate light. My long search eventually led to a PhD, necessary to delve further into the phenomena of archaeoastronomy that I taught many times at the university level.

When studies of archaeoastronomy were first published in the 1970s, the academic community was skeptical and slow in accepting most examples of astronomical alignments of buildings, temples, tombs, and even entire cities. The astronomy of the Stonehenge was the most obvious example, and that was presented by a very qualified astronomer with computer-devised evidence. On occasion, research and new theories involving archaeoastronomy arose from diverse disciplines outside of astronomy, archaeology, or traditional academic circles; these amateur studies were rejected immediately. Even studies published by tenured archaeoastronomers were regarded with a discerning eye; it was thought that the most primitive cultures were not thought capable of such abstract thought and could not have understood astronomy.

Specialists studying physical evidence of astronomical knowledge in early cultures often suffered from a lack of regard by colleagues who followed more traditional and long-established research paths. Since the 1980s, more and more evidence has been uncovered in this burgeoning field. The findings have been steadily gaining recognition and acknowledged authenticity by more conservative astronomers and archaeologists. Fortunately, those initial biases have been proven faulty, and the capabilities of Neolithic peoples and the earliest cultures are now becoming more fully understood. Dating of these ancient sites continues to reach further and further into the past. Now, archaeoastronomy has advanced to become an interdisciplinary field with contributions from a wide range of academic areas.

Archaeoastronomers are now crossing paths with specialists in anthropology, archaeology, architecture, astronomy, cosmology, philosophy, mythology, statistics, and in many areas of history, including the history of art, religion, literature, acoustics, and science. They have discovered that astronomy has been influential in all aspects of human life, especially agriculture and navigation. Specialists search for information in written as well as unwritten examples in order to shed greater light on every area; they are now meeting and working together in holistic ways. Computer programs now calculate in an instant any stellar or solar position at any past date and at any geographical location. Originally focused on monumental megalithic structures and ancient architecture, archaeoastronomy has expanded into most aspects of human culture. Astronomical information has been found encoded into paintings, ceramics, weaving, poetry, legends, myths, burials, and city planning.