Other Books of Interest:

BEYOND EINSTEINS UNIFIED FIELD

LIFE & DEATH ON MARS

COSMIC JESUS

THE CASE FOR THE FACE

EXTRATERRESTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY

INVISIBLE RESIDENTS

THE COSMIC WAR

SECRETS OF THE UNIFIED FIELD

ANCIENT ALIENS ON THE MOON

ANCIENT ALIENS ON MARS

ANCIENT ALIENS ON MARS II

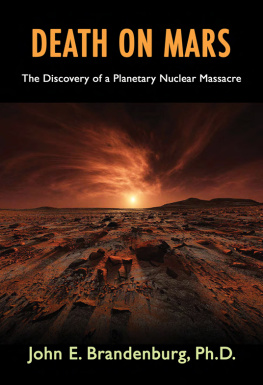

DEATH ON MARS

by John Brandenburg Ph.D.

Copyright 2015

ISBN 13: 978-1-939149-38-1

All Rights Reserved

Published by:

Adventures Unlimited Press

One Adventure Place

Kempton, Illinois 60946 USA

www.adventuresunlimitedpress.com

First Printing January 2015

Dedication:

To the first humans to land in Cydonia

Prologue: The Outer Bridge

For now we see through a glass darkly, but someday, face to face.

The Apostle Paul: 1st Cor. 13: 25

It is Thanksgiving Day when I begin to write this account of this great and terrible discovery of the age. On Thanksgiving Day we examine our lives and existence and give thanks to God and our fellow human beings for our many blessings, one of which is life itself.

Like the day on which I begin this tale, this book is actually a prayer, a prayer that humankind will realize how fortunate they are to have this Earth and each other and, in realizing their good fortune, will move forward to secure those fortunes. For beyond the fair circle of the Earth lies the abyss of space, and across that abyss lies the Red Planet, Mars. On Mars, as desolate as the Earth is rich in life, is a story carved and burned into its rocks, whose telling is both wondrous and terrifying. It is a tale of abundant life and catastrophic death, a tale of scientific discovery as epic as any seen in history, and a warning as astonishing as it is chilling.

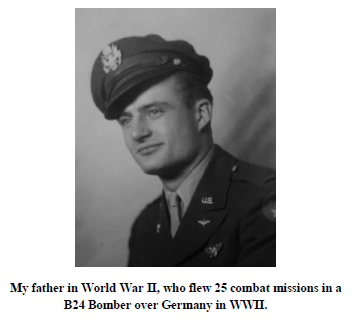

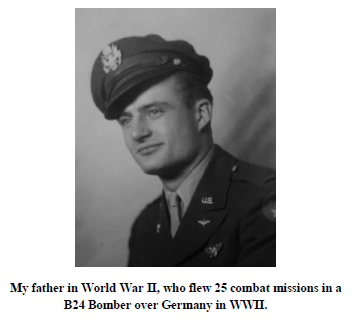

My story begins in picturesque Albuquerque, set in the painted desert of the southwest in the icy depths of the Cold War, near one of the many ground-zeroes of that conflict. There, I had assumed a job working on directed energy weapons at a great national research Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, named for the red hued Mountains to the east of Albuquerque. I was working in the nations defense trying to perfect a new beam of destruction to rival the laser beam. I had always been a very patriotic individual, and my father and uncles were combat veterans of World War II. My father had survived the loss of three-quarters of the bomber squadron he flew with, but he would only ever attribute this fact to dumb luck.1 Accordingly, contributing to the nations defense was second nature to me. But the Cold War, with its threat of mutual nuclear holocaust, seemed to me an intellectual nightmare, and I was on its intellectual front lines. I had been to Russia and toured it for two weeks as a college student. I had returned from there even more patriotic, but also with a deep love of the Russian land and people. Now the sight of Russian mothers weeping over their dead sons, killed in Afghanistan, on the news, filled me with deep sadness.

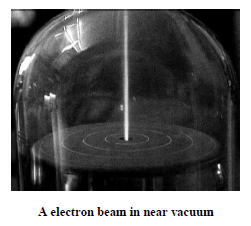

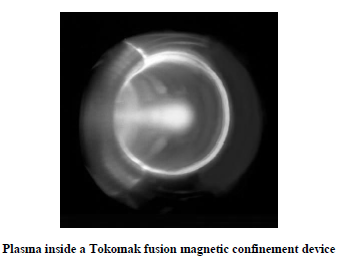

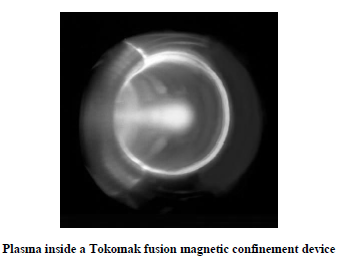

At Sandia we were trying to launch beams of high energy electrons through the air, a sort of directed lightning bolt. The electrons would come hurtling out of an accelerator, which happened to be of Russian design, and, in theory, were to fly straight toward a target at nearly the speed of light, strike it and deposit there energy all through it like x-rays, so that it would explode into white hot vapor. However, the powerful electron beams, like the lightning bolts that graced the skies over Albuquerque so abundantly, refused to fly straight. The electrons, like a flock of nervous sparrows, would dart this way and that, and end up flying in a random sinusoidal path, in defiance of any attempt to aim them precisely. The electrons were reacting dynamically to the electrically conducting plasma they created while boring a hole through the air. Plasma is the fourth state of matter, an electrically conducting glowing gas that makes up the stars, the aurora, the neon sign, the lightning, and 99% of the universe. The problem was that the plasma forming in the air around the electron beams, being an electrical conductor like polished metal, was creating a reflection or image current to the electron beam, and the electron beam was being repelled by its own image. So the beams would penetrate the air, forming a plasma sheath around themselves, see their own reflection in it, and thrash around furiously trying to escape it. I had been hired by Sandia labs, in effect, to be a psychiatrist to the electrons, and teach them, if possible, not to be afraid of their own reflections. So they would fly straight and do their grim work on the targets we directed them to. Plasmas are what I was trained to work on as a scientist.

I had been trained to work on plasmas to solve the great problem facing humanity, the problem of energy. I completed my Doctoral Thesis on the problem of confining plasmas, hotter than the center of a star, so humanity could enjoy controlled fusion energy, a safer and cleaner form of nuclear power. That is, I and my colleagues had tried to bring the power of the stars to Earth. I had done my doctoral work under the brilliant Richard F. Post at another government research laboratory, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. We had made enormous progress on the problem of controlled fusion while I had been working there. However, with the change of administrations from Carter to Reagan had come a change in priorities. Controlled fusion research was to receive less funding. The icy flames of the Cold War were to be stoked instead. So my dreams of helping to ensure a bright warm future for humanity had been crushed as I had searched vainly for a job in controlled fusion in a time of tightening budgets. Instead, in order to fulfill my promise to my wife of a good job, nice house, and affluence after the privations of graduate school, I had taken a job in directed energy weapons research. It was a tough intellectual transition for me, but I had always tried to be tough. I was lucky to have gotten the job I had, but it came at a cost.

At Livermore, administered as part of the University of California, science had been conducted in a mostly academic manner, as far as I could tell, buried deep in the Magnetic fusion energy section. But I knew that at the other end of the vast laboratory, the physics and basic design of hydrogen bombs were being researched for the nations arsenal. The graduate school I attended had the informal name of Teller Tech, after its founder Edward Teller, a man I deeply respected. Teller had helped convince Einstein to sign a letter warning Franklin Roosevelt about the danger of Adolf Hitler gaining an atomic bomb ahead of the U.S. and Britain in World War II- a very real threat. Edward Teller had later invented the Hydrogen Bomb, staying just one step ahead of Andrei Sakharov, who was developing it for Joseph Stalin. So I was proud to be a graduate of his school.