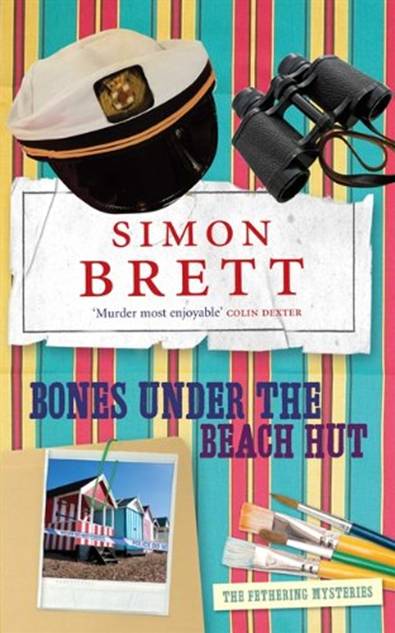

BonesUnder The Beach Hut

SimonBrett

First published 2011 by Macmillan

an imprint of Pan Macmillan, a division of MacmillanPublishers Limited

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke andOxford

Associated companiesthroughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-230-73638-2

Copyright Simon Brett 2011

The right of Simon Brett to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him inaccordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library.

Typeset by CPI Typesetting

Printed in the UK by CPIMackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

To Bruce and Ros

And also to Sonja Zentner

who, at the 2010 Chichester Cathedral

fundraisingFestival of Flowers, won the right

to have her nameincluded in this book.

Table of Contents

ChapterOne

Thereweren't many proper beach huts on Fethering Beach. Just a few ramshackle shedsonce owned by fishermen, which had been converted for use by holidayingfamilies. For proper regimented beach huts, with pitched roofs and theproportions of large Wendy houses, you had to go west along the coast to theneighbouring village of Smalting. And it was there that Carole Seddon had theuse of a beach hut for the summer.

Smaltingwas a picturesque - very nearly bijou - West Sussex village, whose inhabitantsthought themselves superior to the residents of Fethering. In fact, theythought themselves superior to the residents of anywhere. Like many of thevillages along that stretch of coast, the earliest extant buildings werefishermen's cottages, which had been refurbished many times, ending up aselegant well-appointed dwellings, mostly bought by comfortably pensioned peopledownsizing in retirement. A couple of large houses had been added to thevillage in the eighteenth century, and a few more spacious holiday homes hadbeen built by the late Victorians. In the first decade of the twentiethcentury, Smalting had become a fashionable seaside resort and rows of neatEdwardian terraces had sprung up. In the nineteen thirties two private estateshad been developed either side of the village, and with that further buildingstopped. Unlike Fethering, Smalting did not spread northwards and so did nothave room for any of what was still disparagingly referred to as 'councilhousing'. The army of cleaners and home helps who serviced the needs of itsresidents all came from outside the village.

Nobodydid any basic shopping in Smalting. There was nothing so common as asupermarket. The newsagent was the nearest to a practical shop in the village,selling milk and bread as well as more traditional stock and beach items forholidaymakers. The other retailers were highly expensive ladies fashionboutiques, tiny craft galleries and antique dealers. Facing the promenade stooda row of dainty tea shops. Smalting's one pub, The Crab Inn, had such adaunting air of gentility about it and such high prices for food that it wasrarely entered by anyone under thirty. But it did very well from theover-sixties.

Thebeach huts conformed to the high standards that were de rigueur for everythingelse in Smalting. There were thirty-six of them at the back of the beach, justin front of the promenade, and they were divided into three slightly concaverows of twelve. Eight foot in height and width, each one was ten foot deep andset on four low concrete blocks. They were painted identically - thebitumenized corrugated roofs green, the wooden walls and doors yellow and bluerespectively. Touches of individualism were clearly discouraged, though aconsiderable variety of padlocks was on show, and some of the owners hadindulged in rather elaborate name signs. These tended to feature anchors, coilsof rope, shells and painted seagulls. The names chosen - Seaview, SaltSpray, Sandy Cove, Clovelly, Distant Shores and so on - didn't demonstratea great deal of originality.

Thebeach hut of which Carole Seddon had use was called Quiet Harbour, andshe felt rather guilty about her new possession. This was not unusual forCarole. Despite her forbidding exterior and controlled manner, inside she was amass of neuroses, though this was something that she would not acknowledge toanyone, least of all herself. She had been brought up to believe that everyoneshould be self-sufficient, that turning to others for help was a sign ofweakness. Afraid of revealing her true personality, Carole had always tried tokeep people at arm's length, not allowing anyone to get close to her. This hadcertainly been her practice during her career at the Home Office. She had alsotried to keep her distance within marriage, which was perhaps the reason whyshe and David had divorced.

Andwhen she had moved permanently to Fethering in retirement (early retirement)Carole Seddon still kept herself to herself. She had acquired a Labrador calledGulliver for the sole purpose of looking purposeful, so that her walks acrossFethering Beach did not appear to be the wanderings of someone lonely, but theessential behaviour of someone who had a dog to walk.

Sointimacy was not a natural state for Carole Seddon. Even Jude, her neighbourand closest friend, sometimes found herself shut out. Carole was hypersensitiveto slights, quick to take offence. And she worried away about things.

Justas she was now worrying away about her use of Quiet Harbour. Like manypeople who lack confidence, Carole was wary of breaking even the most minor ofregulations. There were many things in her life that she couldn't control, butone thing she could was keeping the right side of the law. Her work at the HomeOffice had encouraged her natural law-abiding tendencies, and she would try toavoid even tiny infringements, like keeping out a library book beyond its duedate or being twenty-four hours late in applying for the road tax on herRenault. And Carole wasn't convinced that her using the beach hut was entirely,100 per cent legal.

Thecontact had come through Jude, inevitably from one of her clients. In WoodsideCottage, the house next to Carole's High Tor, Jude worked as a healer andalternative therapist. Neither of these job descriptions cut much ice with herneighbour, who regarded as suspect any medical intervention that wasn't carriedout by a traditionally qualified doctor. Whenever the subject of Jude's workcame up in their conversations, Carole had to keep biting her lips to preventthe words 'New Age mumbo-jumbo' from coming out of them. But she had to admitthe benefits of her neighbour's work when it came to broadening their social circle.And on more than one occasion, it had been through a client who had come toWoodside Cottage for healing that Carole and Jude had become involved incriminal investigations.

Itwas in the role of client that Philly Rose had come to Jude. She was crippledby back pain and, as was so often the case, the cause of the agony lay in hermind rather than her body.

Philly,in her early thirties, and her older boyfriend Mark Dennis had moved down fromLondon to Smalting some six months before, just at the beginning of January.For both of them it had been a new start, Philly giving up employment as agraphic designer to go freelance and Mark chucking his highly paid City job todo what he'd always wanted and be a painter. Cushioned by his savings and recenthuge bonus, the two of them had embraced country living, involving themselvesin everything that the South Coast had to offer. Their two sports cars weretraded in for a Range Rover. They acquired two cocker spaniels, bought asailing dinghy, planted their own vegetables. Both took a lot of exercise. Marklost the extra weight put on by his City lifestyle. Their make-over seemedcomplete.