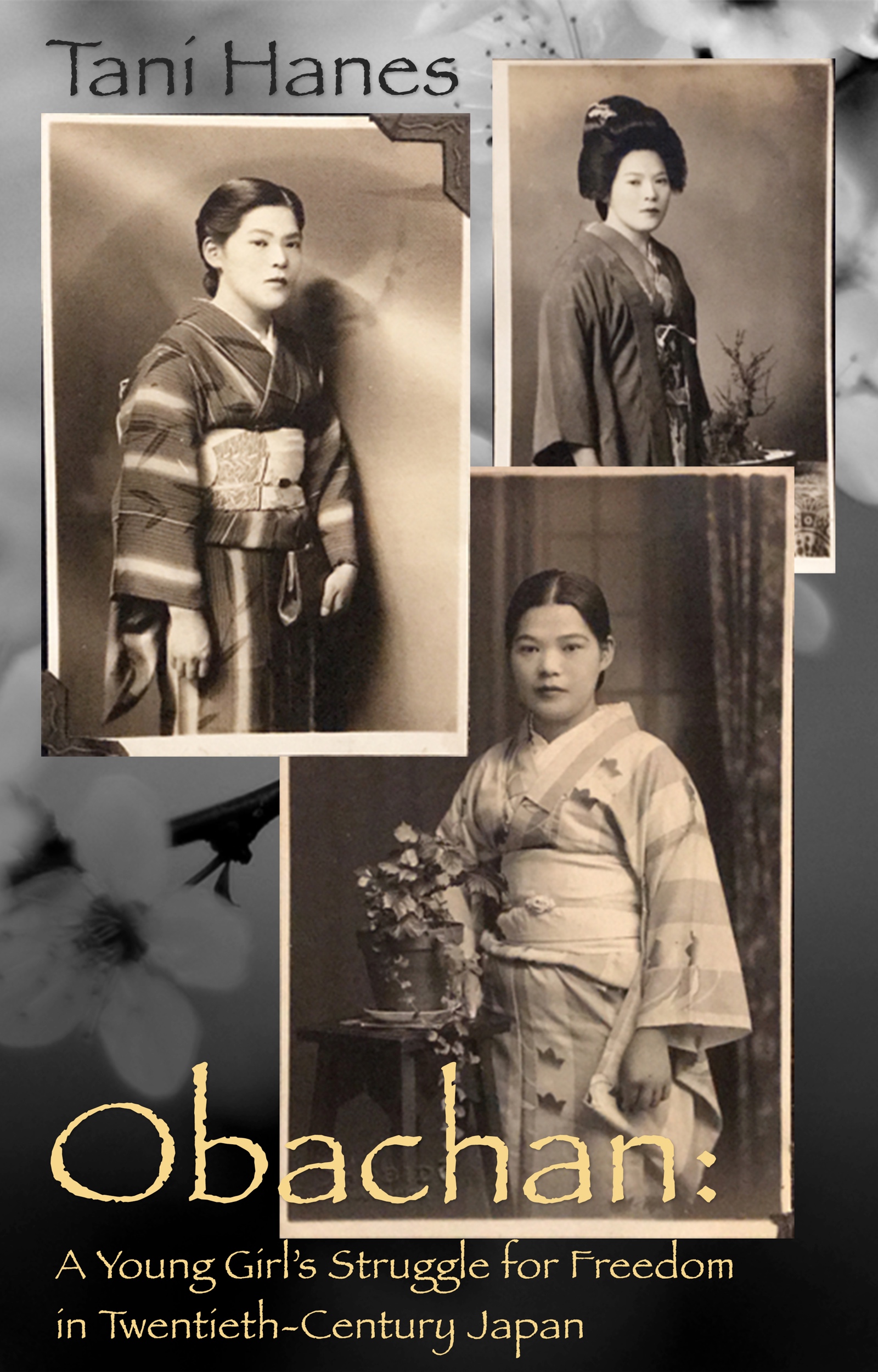

I never realized my obachan was an unhappy woman until I asked her one evening if she loved my grandfather. She said of course she didnt.

I stared at her.

I asked how she could bear to be touched by him, then, and she told me matter-of-factly that she couldnt. She couldnt!

This shocked me. It had never occurred to me that shed feel this way about him. Shed married him, after all. Dont get me wrong, I believe there was affection between them. They were married for nigh on half a century, how could there not be? But romantic love? I dont think so.

This was what led her to tell me her life story, in bits and pieces, whenever my baby was asleep, or as wed sip iced tea at my house in California. And that was when I realized that I never really knew her at all, and the clock was ticking if I wanted to change that.

So heres my attempt. I hope, wherever she is, shes pleased with it. And that shes surrounded by flowers and noshing on the biggest piece of cake.

She sure as hell deserves it.

T he full moon shone down on the sleeping village. It was sinking in the west, illuminating many square ri of rice fields, filled with top-heavy stalks of ready-to-be-harvested rice. Walkways divided the paddies into symmetrical shapes, framing the fronds into rustling squares.

Twelve-year-old Mitsuko lay on the pallet that she shared with two of her younger sisters, twisting and turning as she tried to sleep. Her back was sore from a day spent tending the rice, and she counted the days until the harvest would be over and she could return to school. It was the autumn of 1928, and she had missed nearly a full month already.

Suddenly a candle was thrust in her face, and she heard her mother's voice.

"Good, you're still awake. Come in the other room. Your father and I want to talk to you."

She got out of bed without a word and threaded her way between the sleeping bodies of her brothers and sisters.

Her father was sitting on the only chair, so she stood in front of him, while her mother, still holding the candle, went to stand behind. He cleared his throat.

"You know that the harvest this year won't be very good."

Mitsuko nodded. The harvest was never good; it was too warm. Niigata, which was a three-day ride to the north, was where the high-quality rice was produced.

"You are young and fat," he said. Everyone knew that fat people didn't get sick as often. "Your aunt and uncle have no children, and they have agreed to adopt you and make you their heir. They will teach you how to run their farm, and someday, you will inherit it." He leaned back, signaling that he was finished speaking.

Her mother spoke now, leaning forward and making the candle flicker. The flame danced and stretched, sending up wispy curls of smoke. "You've always been a lucky child. You survived the malaria that killed your older sister, and you're so sturdy."

Mitsuko stared at the candle as the flame guttered dangerously. She thought of the school where she went, the school that was an hour's walk from her house. Her aunt and uncle lived half a day's journey in the opposite direction.

"They won't be coming for you until early next year, because we'll need you through the worst of the winter," her mother continued. A dollop of wax fell with a hiss to the floor. "Work hard for them, and don't make us ashamed of you."

The candle flame guttered for the final time and burned out.

Mitsuko fidgeted with the front of her hanten, the heavy winter garment shed tied over her least worn kimono. She wiped the steam off the window facing the road, trying to see if more snow had fallen during the night. Although it was March, spring was still two weeks away, and if there was fresh snow, her only good shoes would be soaked by the time she reached the school.

She was startled by her sister Hanako's voice. She'd thought that she was the only one awake.

"You know that Ma won't let you go to school," she said from the pallet they shared. "Aunt and Uncle are coming to get you."

Mitsuko only nodded.

"Didn't you tell your teacher that you wouldn't be able to come today, that you wouldn't be able to give the graduation speech?"

Mitsuko shook her head, biting her lip.

"Well, if you're going to go, you'd better get going now, before she wakes up."

As Mitsuko opened the door, her sister said, "If she asks me where you went, I'll just tell her that I don't know."

Mitsuko flashed a grateful smile and stepped outside.

The day was bright already, and fiercely cold. The air was so clear that she felt she could reach out and touch Mount Fuji, though it was a two-day ride to the southeast. It rose sharply from the plains, dusted in white from top to bottom, contrasting sharply with the dark blue sky.

She hurried along the road, blowing on her fingers to keep them warm. Her breath came out in smoke-like puffs, like the plow horses in the Hayashi's field when they were working hard.

She came to the bridge that spanned Kawara Creek and crossed it quickly, not taking time as she usually did to stop and watch the water as it wound its way beneath her. Mount Fuji was the only thing in her field of vision that hadn't changed position since she'd left her house.

She heard the far-off whistle of the train and, even more faintly, the clicking of its wheels against the steel rails on which it rode. That had to be the morning freight, which meant that it was already after eight o'clock. She quickened her brisk step, thinking of her speech, of how proud she'd been when selected to give it. She smiled to herself.

The smell of cooking fish reached her, a smoky, salty smell, reminding her that she hadn't had any breakfast, and only rice for dinner the night before. She tried to take her mind off it, but her disloyal stomach began to growl and, finally, to cramp from hunger.

She bent down and scooped up some snow in her chapped hands. It felt soft, like the finely shaved ice that she'd been lucky enough to eat one summer, although that ice had had strawberry syrup on it. She packed it with her two hands into roughly the shape of a rice ball, and felt it harden, losing its velvety texture and becoming like a piece of the lava she sometimes found in the field. She took a bite. It tasted like the outdoors, like the wind that whipped around her ankles. She chewed on it, enjoying the squeaky texture of the snow against the flat of her back molars. The minerals in the snow left a tingling on her tongue, and she swallowed it and took another bite. She resumed walking, periodically taking bites of her snowball.