Contents

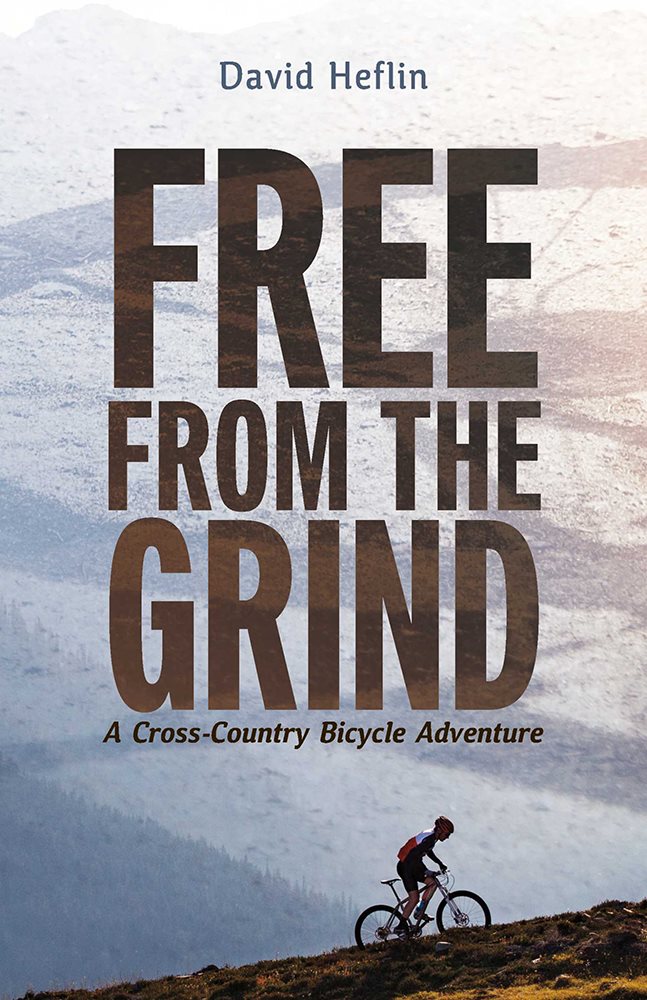

Free from the Grind:

A Cross-Country Bicycle Adventure

2020 David Heflin

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

print ISBN: 978-1-09832-804-7

ebook ISBN: 978-1-09832-805-4

DEDICATION

To my family and friends, who sacrificed so much to allow me to experience pilgrimage. To my wife, Suzy, and my children, Katy, Brent, and Kelly Anne, who sacrificed the most. And to my friends, who quietly supported, and challenged, my plans for a special adventure.

PREFACE

S pring is typically a no-show in South Dakota. The months of March and April punish the people of the frigid northern plains, as winter doesnt yield to spring dependably until Mothers Day. While azalea bushes perfume the languid spring days in my native Mississippi, South Dakotans struggle under the burdens of heavy snows and bone-chilling temperatures. Its during these months that the other challenges of life grow, and South Dakotans flee the ice-cold plains for relief.

In 2005, I experienced the burden of the South Dakota spring and looked for relief. I was at such a point in my life that I felt a trip was necessary. Ishmael, in Herman Melvilles Moby Dick , explains his need to go to sea:

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking peoples hats off - then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship.

In the late spring of 2005, I quietly took to the road in search of an attitude adjustment. The dull routines of fifty-five-hour work weeks, diapers, snowblowers, and bills challenged me to find an experience that would snap me out of a serious slump. I needed something transformational.

A trip is often more than transit from one location to another. A trip may be a pilgrimage. A pilgrimage is a journey embedded with meaning, and this meaning often emerges from the telling and retelling of the stories that make up the journey. At the age of forty-four, I put my life on hold and challenged myself to ride a bicycle 2,900 miles across the country in twenty-eight days. This book is a collection of the stories that reveal the answers to the questions people have asked.

These questions came early from supporters and detractors. These questions came in different forms. Sometimes the questions were spoken, sometimes they were unspoken. Have you lost your mind? Do you have any idea what youre getting into? Do you know how stupid youre gonna look when you fail?

My wife, Suzy, was both supportive and confident in my dreams of adventure, but she had doubts. I know I had plenty of doubts and questions. Would my legs and heart arrythmia survive the daily marathon-like mileage required to finish the trip in twenty-eight days? Would I be safe riding alone in remote areas of the country? Would my detailed planning support a solo 2,900 miles race across America?

After the trip, people asked other questions. Why would you attempt this? How long did it take you to finish? What did you learn? For the answers, read on.

INTRODUCTION

T wo uniformed Transportation Security Administration officials cornered me behind the luggage belt of the security screening area of the Sioux Falls, South Dakota, airport. I had attempted to pass security for a flight to Phoenix, Arizona, and the officers pulled me over for questioning. The two stood between me and my plane, adding to the stress of arriving late to the airport.

My adrenaline spiked, and my senses swelled as I waited for them to tell me what Id done wrong. I looked past the officers toward the main terminal and my destination. The sensory wonderland of the airport sharpened my fear of missing my plane.

A nearby coffee shop greeted passengers to the main terminal. Coffee beans rattled in a grinder, and aromas of fresh-baked bread and roasted coffee filled the air. My stomach rumbled from hunger. I was late for my plane, and I had skipped lunch. I had hoped to grab a coffee and croissant, but a line snaked from the coffee shop counter into the main terminal walkway. An electric passenger shuttle parted the bread line and buzzed down the corridor to deliver its latest payload. Airplane pretzels and stale coffee would have to suffice.

Noise from the loudspeaker bounced off the floor-to-ceiling windows that overlooked jets thundering off the concrete landscape. A genderless voice trumpeted a series of gate changes, late arrivals, and last calls for flights. I listened anxiously for the last call for my Phoenix flight.

Passengers gathered their bags from the security area screening belt and scrambled past me into the main terminal area. The officers had dumped my bags on a long metal table under the South Dakota and United States flags. They rifled through the contents wearing latex gloves and serious expressions.

The male officer wearing a badge, a white shirt, and a red tie, clanked two pieces of my bicycle handlebar extensions together, struggling to combine the two. He shrugged his shoulders and replaced the parts on the table. He lifted a green fuel bottle, unscrewed the cap, and sniffed the contents.

He winced. This is a fuel bottle. He screwed the cap back on and returned the bottle to the table.

Yes, sir. But its empty, the other official offered. The female official, wearing a blue shirt and black tie, smiled and retrieved the bottle. She shook the empty bottle next to her ear and shrugged at the other officer as if asking a question. Not receiving any feedback, she replaced the bottle and returned to her position at the scanner.

The male officer looked back at me and seemed to be inspecting my appearance. I didnt look like an average Sioux Falls passenger. Wisps of hair on the top of my head grew thick and shaggy over my ears and neck. I hadnt used a razor in weeks, and I had the appearance of a forty-four-year-old who was trying to grow a beard for the first time. My wardrobe consisted of bulky black cycling shoes, baggy knee-length khaki cycling shorts, and a tight yellow T-shirt stained with bicycle grease.

The alarm on my oversize black sports watch rang a late warning. According to my travel documents, boarding should have started twenty-five minutes earlier, and my plane should be wheels up in ten more. The timeline of my trip, riding a bicycle over 100 miles per day for twenty-eight consecutive days, didnt provide any cushion for a missed flight. The clock ticked.

I had packed for the trip in a hurry. I carelessly placed two empty fuel bottles, a camping stove, and a small bag of bicycle tools into two carry-on crimson panniers. The panniers resembled saddlebags that would be attached to the rear wheel assembly of the bicycle. The security scanner quickly identified a problem with the panniers, and she called the second official for assistance.

Sir, are these your bags? The officer took charge of the questioning.

Yes, I said.

Could you please give me your name and address? He pulled a small spiral-bound notebook from his shirt pocket and began to scribble with a stub of a pencil.

David Heflin, I said and shook my head. I felt my frustration build, and I thought for a moment that I was being unfairly treated. I put those thoughts aside and provided my address.