Phocion Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

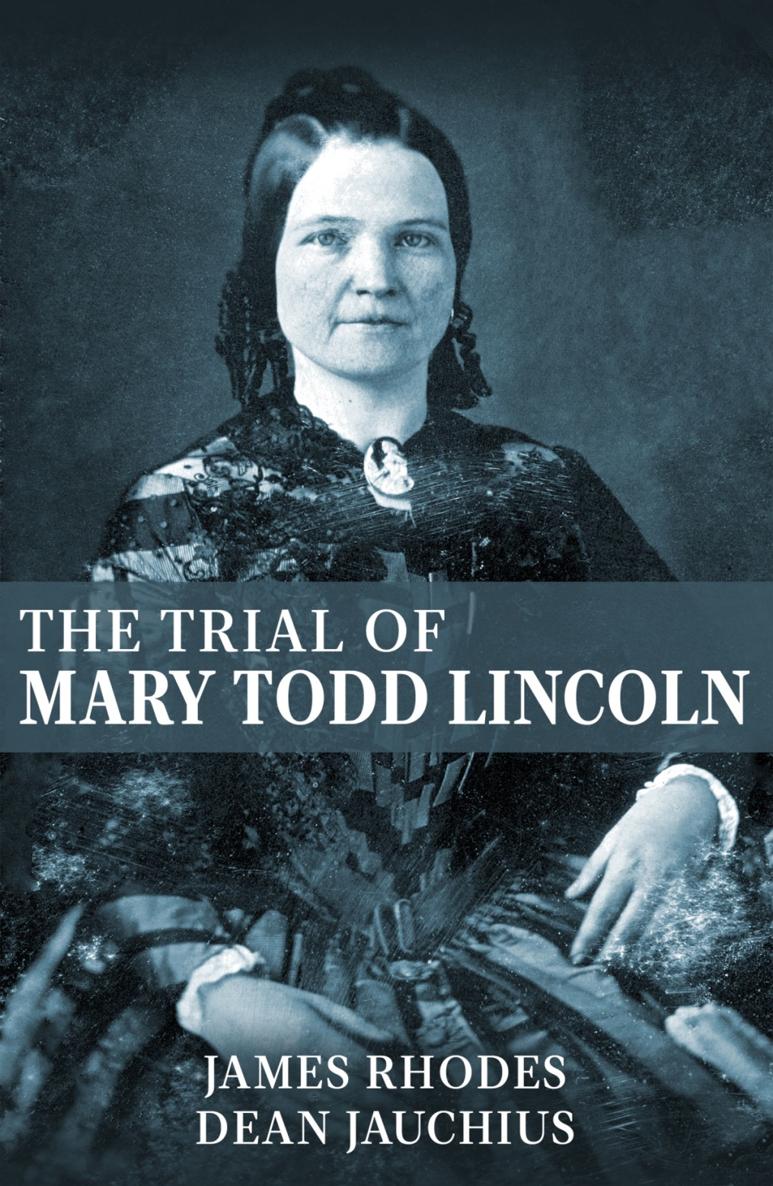

The Trial of Mary Todd Lincoln

JAMES A. RHODES and DEAN JAUCHIUS

The Trial of Mary Todd Lincoln was originally published in 1959 by The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., Indianapolis and New York.

Counsel for the Defense

It is easy to think of Mary Todd Lincoln as one of the heavy burdens Abraham Lincoln bore without complaint. According to tradition, she was unpredictable, hysterical and unbalanced. Lincoln students in the main have accepted this estimate without fully examining the facts. Some, indeed, have done her the injustice of apologizing for her.

The authors undertook to find out whether history had treated her fairly. On the surface, the sanity hearing which declared her a lunatic was the most damaging count against her. In their investigation of this proceeding they discovered something wrong. She was no more eccentric than many around her. The authors digging uncovered a strong odor of kangaroo court. The brazen injustice of this trial, the high-handed denial of her civil rights made a travesty of the verdict and called for a broader reexamination. They found that during the years in the White House she had let herself appear in an unflattering light in order to shield and guard her husband. They came to hold an entirely new picture of this anguished woman.

The authors were convinced that Mary deserved her day in court, and had never had it. And certainly she deserved a more sincere and searching defense than she was ever given.

Neither in the mental hospital to which she was condemned, nor at any time previously, had she had any of the benefits of modern psychiatric treatment. She stood alone, unprotected. Because of her valiant struggle and because of her great love and devotion to her immortal husband and her sons, she deserves a better niche in our history than the one to which she has been consigned.

The legal and medical philosophy behind the snake pit laws which summarily put her away operates today. In large areas of the country many of these same laws are still in force.

These are our thoughts as we complete The Trial of Mary Todd Lincoln .

JAMES A. RHODES

DEAN JAUCHIUS

Chapter 1

A LITTLE MORE than ten years after the death of her martyred husband, Mrs. Abraham Lincoln was placed under arrest, taken into custody under threat of violence, hailed summarily into a courtroombefore a jury already impaneled, sworn and waitingtried, found insane, ordered confined in an institution and stripped of approximately $56,000 in cash and securities.

By nightfall of the following day, she sat alone in the gloom of a room with barred windows, branded by court order as Mary Lincoln, Lunatic. And in the enforced solitude of that room, she could contemplate that she had been made the victim of an elaborately contrived and smoothly executed plot to put her away. She could ponder the fact that three of the men involved most prominently in that plotting had been intimate friends of her late husband. Indeed, two of them had maneuvered for him the Republican presidential nomination of 1860 and then prodded and pushed him down the political trail to the White House. Mary Todd Lincoln could think, too, that this scheme which they had planned so carefully against her had, to achieve its end, required denial of every constitutional and statutory right afforded the accused. And she could reflect, bitterly, that it had utilized as its primary instrument her eldest and only surviving son. It was cruel irony that through his eldest son, men who had been his best friends had managed to take away the freedom of the desolate and troubled widow of the man universally hailed as The Great Emancipator.

It actually happened.

The place was Chicago, Illinois.

The day was Tuesday, May 19, 1875.

The first sound of it, for Mary Todd Lincoln, anguished widow, was a knock at the door of her room in the Chicago Grand Pacific Hotel.

The time was about 1:00 p.m. Here are the facts: When Mary Lincoln opened that hotel-room door, three people greeted her. They were a delivery boy, Leonard T. Swett, a prominent Chicago lawyer who had helped secure the presidential nomination for Abraham Lincoln at the convention of 1860, and Samuel M. Turner, manager of the hotel.

The bundle boy delivered eight pairs of lace curtains which Mary Lincoln had purchased earlier in the day. He left immediately. Swett, who wrote later that Mary Lincoln seemed cheerful and glad to see him, entered the room followed by Sam Turner, and advised Mrs. Lincoln that she was under arrest. About that time, according to Swett, Turner left the room.

Mary Lincoln was ladylike but firm. The contention that she was insane was preposterous. She was abundantly able to care for herself. Where was her son Robert? Who claimed she was insane?

Swett told her that Robert was waiting for her at the courtroom. He advised her that it was her son who had filed the affidavit necessary to bring her to trial. He said Judge David Davis, conservator of her late husbands estate and the most prominent manipulator in Lincolns behalf at the national convention of 1860, believed her crazy. So did John T. Stuart, mayor of Springfield and her cousin, he added. So did he, Swett, and so did five physicians. Swett produced letters from the physicians for Mary to see.

Mary Lincoln decided stubbornly that she would not go with Swett to the courtroom. Swett said she had no choice in the matter. She had two alternatives, though, as concerned how she was to be taken to court. She could either go peaceably with him, or be handcuffed and taken forcibly by two officers now waiting downstairs. Which would it be?

Mary Lincoln chose to resist with words alone. They were bitter, sarcastic words. She denounced Swett and Judge Davis and Robert. She accused them of having mercenary motives. And yet, Swett testifies, she was ever the lady, never stooping to use of common words or phrases.

When she had finished, Swett insisted again, and he was rock-like and unyielding. It was a court order. She must go with him or the officers. There was no escape.

Mary Lincoln wept then. She threw up her hands and prayed, and called upon Abraham to release her and drive Swett away. And then she gave in.

Swett testifies that he refused to leave the room so that she might change her clothing. He told Mary, he says, that he feared she might commit suicide. And so the resigned Mary Lincoln, erstwhile first lady of the land, stepped into a closet, made the desired changes and went along quietly.