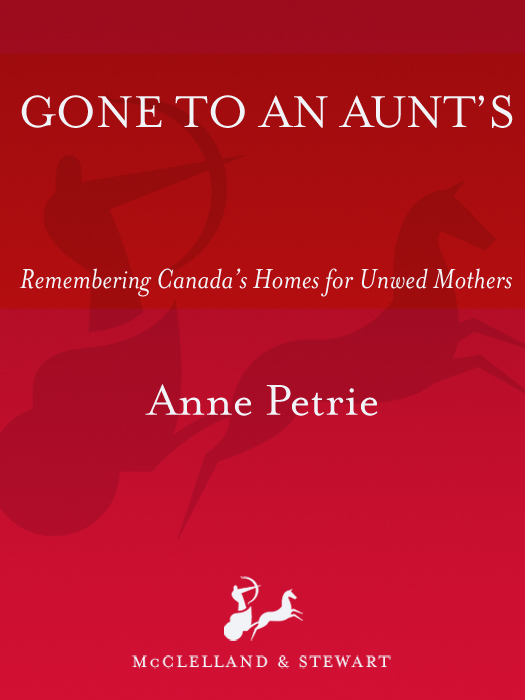

Copyright 1998 by Anne Petrie

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Petrie, Anne

Gone to an aunts : remembering Canadas homes for unwed mothers

eISBN: 978-1-55199-609-7

1. Maternity homes Canada. 2. Unmarried mothers Institutional care Canada. 3. Unmarried mothers Canada Public opinion. I. Title.

HV700.5.P47 1998 362.8392950971 C98-930079-X

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for our publishing activities. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5G 2P9

v3.1

To Pat

CONTENTS

Introduction

We used to pass the home on the way to school. We knew what it was and had a morbid curiosity about the girls who were inside. But we never saw anyone. Ever. I think they frightened us. The whole place frightened us. Like we could end up there. Thinking about it still gives me the shivers.

Barbara S., Vancouver

Up at the crack of dawn. Line up for your food. Do your chores. Say your prayers. Dont talk about the past. No last names ever.

Rules and regulations. Work and religion. Shame and secrecy. What kind of a place was this? Who was it for? Where? When?

When was not so very long ago, only a few decades past, times that many of us still remember well the 1950s and 1960s. Where could have been an old house or maybe a brand-new brick building or something make-do, such as a converted army barracks. You might have found one if you knew where to look in the middle of a busy downtown or secluded in a residential area.

And who was there, lining up for meals and saying their prayers? Girls. Just girls. Rich girls, poor girls. City girls, farm girls. Girls as young as thirteen or fourteen; girls who were no longer girls young women in their twenties, sometimes older. But they were all the same in one respect. They were pregnant and not married. They were, in the vocabulary of the day, unwed mothers.

No one whispers about unwed mothers any more. Or about girls in trouble or young women being knocked up. These are epithets from another generation. To be unmarried and pregnant carries no real stigma today. An adult woman can choose to have a child on her own and her decision is socially accepted, or at least tolerated. A teenager who finds herself pregnant may be considered to be part of a social problem, but not a pariah.

Thats not the way it used to be. In the 1950s and early 1960s, we all knew what it meant to be pregnant and unwed. The warnings were loud and clear: your life would be ruined; you would be kicked out of school, perhaps out of home, and branded a slut or a tramp. You would bring indescribable shame on yourself and your family. You were supposed to just say no. But no was not a fail-safe contraceptive, and many girls found themselves pregnant and mortified.

There were options, of a sort. Abortions could be had, but they were illegal, expensive, and usually dangerous. You could get married, but a shotgun wedding brought its own kind of shame your family and friends either knew or suspected that youd had to get married. If you could get married. Frequently the boy or young man ducked or denied his responsibility. Or the parents said no. Their daughter was too young to marry or this was not the son-in-law they had imagined. The idea of a girl keeping her baby on her own was almost unthinkable. Most often, and regardless of their class or economic circumstances, parents treated their daughters pregnancy as a secret to keep. No one could know not friends, relatives, neighbours, or schoolmates, sometimes not even sisters or brothers.

So the girls just disappeared. The cover stories were vague. Gone to visit an aunt was typical. Occasionally there was a family member in another city who could be trusted, who would take in a niece or a granddaughter, but often parents could not share the secret with anyone. The daughter was shipped off from her own home to another home, a home to hide in until the baby came. A home for unwed mothers.

Every Canadian city and sizeable town had at least one home. Toronto had at least five, Montreal more than half a dozen, but few people had any idea that such places even existed. A friend of mine told me how fascinated and frightened she and her friends were of one home, which they passed on the way to school. Like children who are convinced that a house is haunted, they speculated endlessly on who lived there and why, and what it must be like inside. And, in a sense, the homes were haunted by the castaway girls hidden behind their walls and by the ghosts of the other girls who had passed through and the babies they had given away.

What was it like inside those many homes for unwed mothers? Were they places of punishment? Rehabilitation? Did some girls find a refuge there, a sanctuary from a society all too eager to judge? What did they do all day? Whom did they see? How did they feel about their babies? Was it a time of shame and sorrow, or was there sometimes laughter from girls who had found a way to have a bit of fun? How did they plan for the future?

Gone to an Aunts tries to answer those questions in the voices of the women who were there, women who include me.

The idea for a book about homes for unwed mothers came while I was watching the Robert Altman film Kansas City. It was set in the jazz age of that midwestern town the 1920s and 1930s and one of the many characters whose story wove in and out of the movie was a young, pigtailed black girl sent north by her family to have a baby. I wasnt paying particular attention to her until a brief scene thirty seconds long at most where she is brought to a home for pregnant girls, in this case pregnant black girls. Clutching her cardboard suitcase, shes taken upstairs into a room with half a dozen iron beds and as many hugely pregnant girls, who all gather round to greet the newest arrival.

When I saw this scene, I was mesmerized by something so familiar and yet so strange. I am not black and my own experience was a lot later, but I knew that place. I knew those girls and why they were there and what they were feeling. But until that moment in a darkened theatre, I had never seen a home portrayed before, not in a movie or a book or a play. I had not heard or even spoken of those places since I had been in one, thirty years ago.

In 1967, I went to the Salvation Armys Maywood Home for Girls in Vancouver the same one my friend and her friends used to spy on. I was not as young as the girl in the film, and I came from a white, middle-class, fairly affluent family in Toronto. I had already lived away from home for my freshman year at Carleton University in Ottawa. But now I was pregnant, and even though social mores were beginning to undergo a change that would soon make the need to hide unnecessary and places such as this obsolete, the old rules held firm for me and my family. I was three thousand miles away, but my parents still feared discovery and social stigma. I, too, could not imagine being publicly pregnant. So I went to a home.