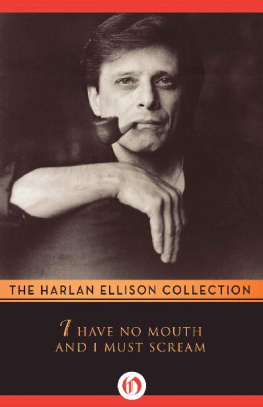

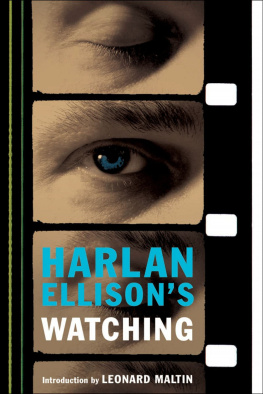

Harlan Ellison

No Doors, No Windows

For Years of Friendship,

for Forcing Open Doors and

Busting Out Windows,

This One, with Love, for

JOE L. and CHARLOTTE HENSLEYI feel its tremendously satisfying to use the cinematic art to achieve something of a mass emotion; if youve [written] a picture correctly, in terms of its emotional impact, the Japanese audience should scream at the same time as the Indian audience.

Alfred HitchcockIntroduction: Blood / Thoughts

Writing has nothing much to do with pretty manners, and less to do with sportsmanship or restraint

Every fictioneer re-invents the world because the facts, things or people of the received world are unacceptable. Every fiction writer dreams of imposing his invention upon the world and winning the worlds acclaim. (Such dreams are known as delusions of grandeur in pathology but tolerated as expressions of would-be genius in bookstores and libraries.) Every writer begins as a subversive, if in nothing more than the antisocial means by which he earns his keep. Finally, every fantasist who cannibalizes himself knows that misfortune is his friend, that grief feeds and sharpens his fancy, that hatred is as sufficient a spur to creation as love (and a world more common) and that without an instinct for lunacy he will come to nothing.

GEOFFREY WOLFF, 1975

What are we to make of the mind of humanity? What are we to think of the purgatory in which dreams are born, from whence come the derangements that men call magic because they have no other names for smoke or fog or hysteria? What are we to dwell upon when we consider the forms and shadows that become stories? Must we dismiss them as fever dreams, as expressions of creativity, as purgatives? Or may we deal with them even as the naked ape dealt with them: as the only moments of truth a human calls throughout a life of endless lies.

Who will be the first to acknowledge that it was only a membrane, only a vapor, that separated a Robert Burns and his love from a Leopold Sacher-Masoch and his hate?

Is it too terrible to consider that a Dickens, who could drip treacle and God bless us one and all, through the mouth of a potboiler character called Tiny Tim, could also create the escaped convict Magwitch; the despoiler of children, Fagin; the murderous Sikes? Is it that great a step to consider that a woman surrounded by love and warmth and care of humanity as was Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, the greatest romantic poet western civilization has ever produced, could herself produce a work of such naked horror as Frankenstein? Can the mind equate the differences and similarities that allow both an Annabell Lee and a Masque of the Red Death to emerge from the same churning pit of thought-darkness?

Consider the dreamers: all of the dreamers: the glorious and the corrupt:

Aesop, Attilla; Benito Mussolini and Benvenuto Cellini; Chekhov and Chang Tao-ling; Democritus, Disraeli; Epicurus, Edison; Faur and Fitzgerald; Goethe, Garibaldi; Huysmann and Hemingway, ibn-al-Farid and Ives; Jeanne dArc and Jesus of Nazareth; and on and on. All the dreamers. Those whose visions took form in blood and those which took form in music. Dreams fashioned of words, and nightmares molded of death and pain. Is it inconceivable to consider that Richard Speck who slaughtered eight nurses in Chicago in 1966, who was sentenced to 1,200 years in prison was a devout Church-going Christian, a boy who lived in the land of God, while Jean Genet avowed thief, murderer, pederast, vagrant who spent the first thirty years of his life as an enemy of society, and in the jails of France where he was sentenced to life imprisonment has written prose and poetry of such blazing splendor that Sartre has called him saint? Does the mind shy away from the truth that a Bosch could create hell-images so burning, so excruciating that no other artist has ever even attempted to copy his staggeringly brilliant style, while at the same time he produced works of such ecumenical purity as LEpiphanie? All the dreamers. All the mad ones and the noble ones, all the seekers after alchemy and immortality, all those who dashed through endless midnights of gore-splattered horror and all those who strolled through sunshine springtimes of humanity. They are one and the same. They are all born of the same desire.

Speechless, we stand before Van Goghs Starry Night or one of those hell-images of Hieronymous Bosch, and we find our senses reeling; vanishing into a daydream mist of what must this man have been like, what must he have suffered? A passage from Dylan Thomas, about birds singing in the eaves of a lunatic asylum, draws us up short, steals the breath from our mouths; and the blood and thoughts stand still in our bodies as we are confronted with the absolute incredible achievement of what he has done. The impossibility of it. So imperfect, so faulty, so broken the links in communication between humans, that to pass along one corner of a vision we have had to another creature is an accomplishment that fills us with pride and wonder, touching us and them for a nanoinstant with magic. How staggering it is then, to see, to know what Van Gogh and Bosch and Thomas knew and saw. To live for that nanoinstant what they lived. To look out of their eyes and view the universe from a never before conquered height, from a dizzying, strange place.

This, then, is the temporary, fleeting, transient, incredibly valuable, priceless gift from the genius dreamer to those of us crawling forward moment after moment in time, with nothing to break our routine save death.

Mud-condemned, forced to deal as ribbon clerks with the boredoms and inanities of lives that may never touch save by this voyeuristic means a fragment of glory our only hope, our only pleasure, is derived through the eyes of the genius dreamers; the genius madmen; the creators.

How amazed how stopped like a broken clock we are, when we are in the presence of the creator. When we see what his singular talents wrought out of torment have proffered; what magnificence, or depravity, or beauty, perhaps in a spare moment, only half-trying; they have brought it forth nonetheless, for the rest of eternity and the world to treasure.

And how awed we are, when caught in the golden web of that true genius so that finally, for the first time we know that all the rest of it was kitsch; it is made so terribly, crushingly obvious to us, just how mere, how petty, how mud-condemned we really are, and that the only grandeur we will ever know is that which we know second-hand from our damned geniuses. That the closest we will ever come to our Heaven while alive, is through our unfathomable geniuses, however imperfect or bizarre they may be.

And is this, then, why we treat them so shamefully, harm them, chivvy and harass them, drive them inexorably to their personal madhouses, kill them?

Who is it, we wonder, who really still the golden voices of the geniuses, who turn their visions to dust?

Who, the question asks itself unbidden, are the savages and who the princes?

Fortunately, the night comes quickly, their graves are obscured by darkness, and answers can be avoided till the next time; till the next marvelous singer of strange songs is stilled in the agony of his rhapsodies.

On all sides the painter wars with the photographer. The dramatist battles the television scenarist. The novelist is locked in combat with the reporter and the creator of the non-novel. On all sides the struggle to build dreams is beset by the forces of materialism, the purveyors of the instant, the dealers in tawdriness. The genius, the creator falls into disrepute. Of what good is he? Does he tell us useable gossip, does he explain our current situation, does he tell it like it is? No, he only preserves the past and points the way to the future. He only performs the holiest of chores. Thereby becoming a luxury, a second-class privilege to be considered only after the newscasters and the sex images and the personalities. The public entertainments, the safe and sensible entertainments, those that pass through the soul like beets through a babys backside these are the hallowed, the revered.