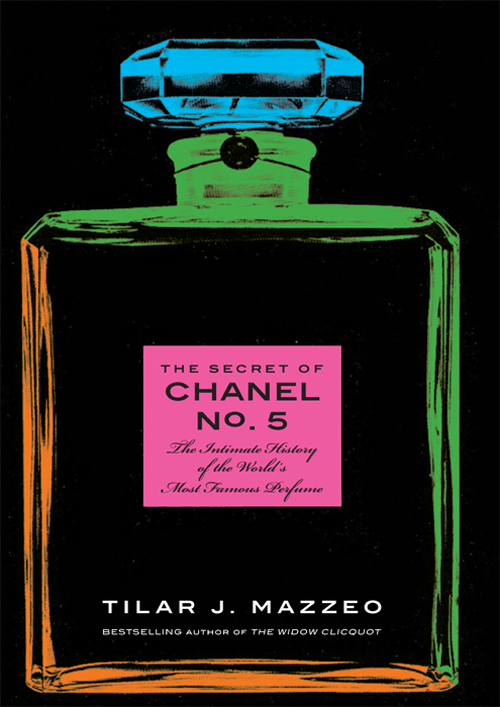

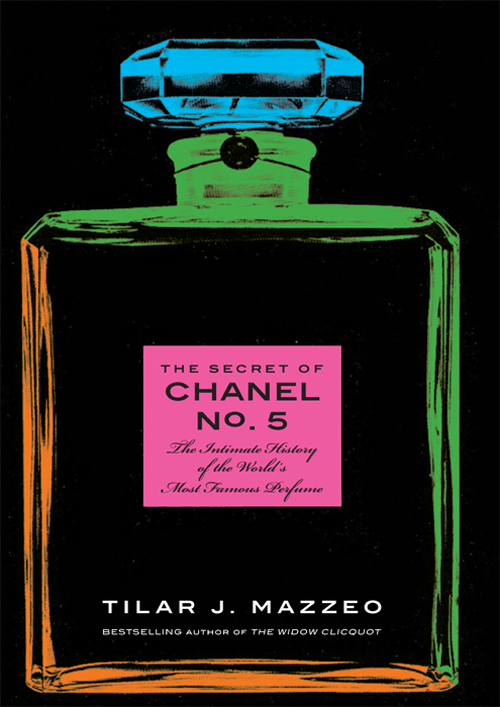

THE SECRET OF

CHANEL N 5

THE INTIMATE HISTORY OF THE

WORLDS MOST FAMOUS PERFUME

TILAR J. MAZZEO

Perfume, its the most important thing. As Paul Valry said it:

A badly perfumed woman doesnt have a future.

Coco Chanel, interview with Jacques Chazot, produced as Dim Dam Dom, director Guy Job, 1969

The most mysterious, the most human thing is smell.

That means that your physique corresponds to the others.

Coco Chanel, quoted in Claude Bailln, Chanel Solitaire(New York: Quadrangle, 1974), 146

CONTENTS

PART I

COCO BEFORE CHANEL NO. 5

ONE

AUBAZINE AND THE SECRET CODE OF SCENT

F or the better part of a century, the scent of Chanel No. 5 has been a sultry whisper that says we are in the presence of something rich and sensuous. Its the quiet rustle of elegant self-indulgence, the scent of a world that is splendidly and beautifully opulent. And, at nearly four hundred dollars an ounce, its no wonder that Chanel No. 5 suggests nothing in our minds so much as the idea of luxury.

Its a powerful association. Chanel No. 5 is sumptuous. In fact, the story of this famous scent is the tale of how a singular perfume captured precisely the fast-living and carefree spirit of the young and the rich in the Roaring Twentiesand of how it went on to capture the worlds imagination and desires. Chanel No. 5, from the moment of its first great heyday, was the scent of beautiful extravagance.

The origins of the perfume and its creator, however, could not have been more different from all of this. Indeed, part of the complexity of telling Chanel No. 5's history is the great divide between how we think of this iconic perfume and the place where it began. Chanel No. 5 calls to mind all that is rich and lovely. Its surprising to think that it started in a place that was the antithesis of what would later come to define it. The truth is that the fragrance that epitomizes all those worldly pleasures began with miserable impoverishment and amid the most staggering kinds of losses.

G abrielle Chanels peasant roots went deep into the earth of provincial southwestern France, and, in 1895, her mother, Jeanne Chanelworn out by work and childbirthsuccumbed to the tuberculosis that had slowly destroyed her. The disease spread quickly in the wet and cold conditions of the rural provinces, and in the nineteenth century it was called consumption for a reason. It ate away at the health of its victims from the inside, corrupting the lungs hopelessly and painfully. Gabriellenamed after the nun who delivered herand her four surviving brothers and sisters had watched it all. She was just twelve years old at the time of her mothers death.

Her father, Albert, was an itinerant peddler, and perhaps he simply had no idea how to care for five young children. Perhaps he didnt particularly care. He had about him a rakish charm and a lifelong knack for dodging responsibility. Whatever the case, in the span of only a few weeks, the young Gabrielle would also lose her second parent. The boys were sent out to work and to make their way in the world as best they could. Albert loaded his three daughters into a wagon without explanation and abandoned them at an orphanage in a rural hillside town in the Corrze, at a convent abbey known as Aubazine.

It was here that the girl who would become known around the world simply as Coco grew up as a charity-case orphan. It was a profound desertion, and the wounds of loss and abandonment were themes that would become as entwined in the story of Chanel No. 5 as they were in Cocos. They formed an emotional register that would shape the history of the worlds most famous perfume and Coco Chanels often complicated relationship to it.

Today, the abbey at Aubazine remains much as it was during her hard and lonely girlhood. Indeed, it remains much as it was during the twelfth century, when the saint tienne dObazineas his name was rendered in the original Latinfounded it. During their time at the orphanage, Coco Chanel and the other girls were assigned to read and reread the story of his exemplary life, and the unrelenting dullness of his good deeds is crushing.

The saintly tienne, however, had a keen sense of aesthetics at a moment when Western cultures ideas about beauty and proportion were in radical transition. He and the monks who followed him to this wilderness in a remote corner of southwestern France were members of the new and rapidly growing Cistercian clerical order, which prized nothing so much as a life and an art of elemental simplicity. tiennes isolated retreat from the world at Aubazine wasand remainsa space of echoing austere grandeur.

The road from the valley that winds up to Aubazine is steep and narrow, and the forests slant down sharply into long ravines. At the summit, there is nothing more than a small village, with a cluster of low stone buildings, a few shops, and quiet houses overshadowed by the looming presence of one of Frances great medieval abbeys. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it had been transformed from a monastery into a convent orphanage for girls. For the children who lived there, it was a youth of hard work and strict discipline and, fortunately for the future prospects of the young Gabrielle, much of it focused on clothing. There was nothing luxurious about it, however. Days were spent washing laundry and mending, and it was here that she learned, of course, to sew.

Coco Chanel once later said that fashion was architecture:

Whenever [Coco] began yearning for austerity, for the ultimate in cleanliness, for faces scrubbed with yellow soap; or waxed nostalgic for all things white, simple and clear, for linen piled high in cupboards, whitewashed walls one had to understand that she was speaking in a secret code, and that every word she uttered meant only one word. Aubazine.

It was at the heart of Coco Chanels aestheticsher obsession with purity and minimalism. It would shape the dresses she designed and the way she lived. It would shape Chanel No. 5, her great olfactory creation, no less profoundly.

Standing amid the scenes of Coco Chanels childhood, the power of Aubazine is obvious. From the exterior, the abbey is an imposing structure of granite and sandy-hued limestone that towers over the village that grew up around it. Inside, it is a contrast of brilliant whiteness and lingering shadows. The keyhole doorways are dark wood against vast expanses of pale stone. There is the cool solidity of arching walls, adorned only with the play of light and the sun streaking in through colorless lead-paned windows. It possesses a striking and silent kind of beauty.

This building was also filled with meanings that would shape the course of Coco Chanels lifeand the life of Chanel No. 5. Everywhere in the world at Aubazine, there were scents and symbolsand reminders of the importance of perfume. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who founded the Cistercian movement, made a point of encouraging his monks to give perfume and anointment a central role in prayer and in rituals of purification. In his famous sermons on the Bibles Song of Songs, some of the most erotic verses anywhere in religious literature, he advised devout clerics to spend some spiritual time contemplating the perfumed breasts of the young bride described in the songs key passages. Soon, someone got the idea that this contemplation would be even more effective if it were combined with time spent simultaneously sniffing the aromas of the local jasmine, lavender, and roses.

Next page