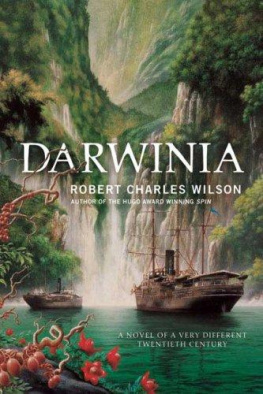

Darwinia

by Robert Charles Wilson

1912: March

Guilford Law turned fourteen the night the world changed.

It was the watershed of historical time, the night that divided all that followed from everything that went before, but before it was any of that, it was only his birthday. A Saturday in March, cold, under a cloudless sky as deep as a winter pond. He spent the afternoon rolling hoops with his older brother, breathing ribbons of steam into the raw air.

His mother served pork and beans for dinner, Guilfords favorite. The casserole had simmered all day in the oven and filled the kitchen with the sweet incense of ginger and molasses. There had been a birthday present, a bound, blank book in which to draw his pictures. And a new sweater, navy blue, adult.

Guilford had been born in 1898; born, almost, with the century. He was the youngest of three. More than his brother, more than his sister, Guilford belonged to what his parents still called the new century. It wasnt new to him. He had lived in it almost all his life. He knew how electricity worked. He even understood radio. He was a twentieth-century person, privately scornful of the dusty past, the gaslight and mothball past. On the rare occasions when Guilford had money in his pocket he would buy a copy of Modern Electrics and read it until the pages worked loose from the spine.

The family lived in a modest Boston town house. His Father was a typesetter in the city. His grandfather, who lived in the upstairs room next to the attic stairs, had fought in the Civil War with the 13th Massachusetts. Guilfords mother cooked, cleaned, budgeted, and grew tomatoes and string beans in the tiny back garden. His brother, everyone said, would one day be a doctor or a lawyer. His sister was thin and quiet and read Robert Chambers novels, of which his father disapproved.

It was past Guilfords bedtime when the sky grew very bright, but he had been allowed to stay up as part of the general mood of indulgence, or simply because he was older now. Guilford didnt understand what was happening when his brother called everyone to the window, and when they all rushed out the kitchen door, even his grandfather, to stand gazing at the night sky,he thought at first this excitement had something to do with his birthday. The idea was wrong, he knew, but so concise. His birthday. The sheets of rainbow light above his house. All of the eastern sky was alight. Maybe something was burning, he thought. Something far off at sea.

Its like the aurora, his mother said, her voice hushed and uncertain.

It was an aurora that shimmered like a curtain in a slow wind and cast subtle shadows over the whitewashed fence and the winter-brown garden. The great wall of light, now green as bottle glass, now blue as the evening sea, made no sound. It was as soundless as Halleys Comet had been, two years ago.

His mother must have been thinking of the Comet, too, because she said the same thing shed said back then. It seems like the end of the world

Why did she say that? Why did she twist her hands together and shield her eyes? Guilford, secretly delighted, didnt think it was the end of the world. His heart beat like a clock, keeping secret time. Maybe it was the beginning of something. Not a world ending but a new world beginning. Like the turn of a century, he thought.

Guilford didnt fear what was new. The sky didnt frighten him. He believed in science, which (according to the magazines) was unveiling all the mysteries of nature, eroding mankinds ancient ignorance with its patient and persistent questions. Guilford thought he knew what science was. It was nothing more than curiosity tempered by humility, disciplined with patience.

Science meant looking a special kind of looking. Looking especially hard at the things you didnt understand. Looking at the stars, say, and not fearing them, not worshiping them, just asking questions, finding the question that would unlock the door to the next question and the question beyond that.

Unafraid, Guilford sat on the crumbling back steps while the others went inside to huddle in the parlor. For a moment he was happily alone, warm enough in his new sweater, the steam of his breath twining up into the breathless radiance of the sky.

Later in the months, the years, the century of aftermath countless analogies would be drawn. The Flood, Armageddon, the extinction of the dinosaurs. But the event itself, the terrible knowledge of it and the diffusion of that knowledge across what remained of the human world, lacked parallel or precedent.

In 1877 the astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli had mapped the canals of Mars. For decades afterward his maps were duplicated and refined and accepted as fact, until better lenses proved the canals were an illusion, unless Mars itself had changed since then: hardly unthinkable, in light of what happened to the Earth. Perhaps something had twined through the solar system like a thread borne on a breath of air, something ephemeral but unthinkably immense, touching the cold worlds of the outer solar system, moving through rock, ice, frozen mantle, lifeless geologies. Changing what it touched. Moving toward the Earth.

The sky had been full of signs and omens. In 1907, the Tunguska fireball. In 1910, Halleys Comet. Some, like Guilford Laws mother, thought it was the end of the world. Even then.

The sky that March night was brighter over the northeastern reaches of the Atlantic Ocean than it had been during the Comets visit. For hours, the horizon flared with blue and violet light. The light, witnesses said, was like a wall. It fell from the zenith. It divided the waters. It was visible from Khartoum (but in the northern sky) and from Tokyo (faintly, to the west).

From Berlin, Paris, London, all the capitals of Europe, the rippling light enclosed the entire span of the sky. Hundreds of thousands of spectators gathered in the streets, sleepless under the cold efflorescence. Reports flooded into New York until fourteen minutes before midnight.

At 11:46 Eastern Time, the transatlantic cable fell suddenly and inexplicably silent.

It was the era of the fabulous ships, the Great White Fleet, the Cunard and White Star liners, the Teutonic, the Mauretania, monstrosities of empire.

It was also the dawn of the age of the Marconi wireless. The silence of the Atlantic cable might have been explained by any number of simple catastrophes. The silence of the European land stations was far more ominous.

Radio operators flashed messages and queries across the cold, placid North Atlantic. There was no CQD or the new distress signal, SOS, none of the drama of a foundering ship, but certain vessels were mysteriously unresponsive, including White Stars Olympic and Hamburg-Americans Kronprinzzessin Cecilie flagship vessels on which, moments before, the wealthy of a dozen nations had crowded frost-rimmed rails to see the phenomenon that cast such a gaudy reflection over the winter-dark and glassy surface of the sea.

The spectacular and unexplained celestial lights vanished abruptly before dawn, scything away from the horizon like a burning blade. The sun rose into turbulent skies over most of the Great Circle route. The sea was restless, winds gusty and at times violent as the day wore on. Beyond roughly 15 west of the Prime Meridian and 40 north of the equator, the silence remained absolute and unbroken.

First to cross the boundary of what the New York wire services had already begun to call the Wall of Mystery was the aging White Star liner Oregon, out of New York and bound for Queenstown and Liverpool.

Her American captain, Truxton Davies, felt the urgency of the situation although he understood it no better than anyone else. He distrusted the Marconi system. The