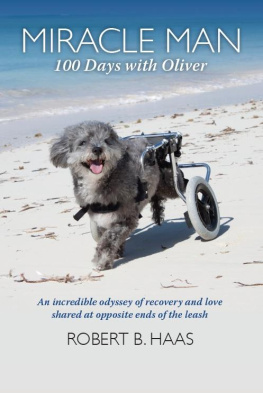

Copyright 2010 by Robert B. Haas

All rights reserved.

ISBN-10: 1-935098-57-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-935098-57-7

Bascom Hill Publishing Group

212 3rd Avenue North, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401

Publish Green Edition

www.publishgreen.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

When we do the best we can, we never know what miracle is wrought in our life, or in the life of another.

Helen Keller

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

From the Author:

I wish to thank my editor extraordinaire Rebecca Ascher-Walsh, who recognized that the true story of the Miracle Man could only be told by examining both ends of the leash, and who cajoled and coaxed that story out of my pen. Without Rebeccas rare gifts of insight and expertise, I would never have done justice to Olivers struggles and to his emergence as the Miracle Man.

From Oliver:

Mark Twain once said, Its not the size of the dog in the fight, its the size of the fight in the dog. I wish to thank all the people in my life who recognized that inside the body of this fourteen-year-old, twenty-pound dog lurked the spirit of a fighter who intended to fulfill the promise of one hundred days: Dr. Julie Ducote, Dr. Emi Hayashi, and the entire staff at the North Texas Emergency Pet Clinic; Dr. Hugh Hays and his devoted staff at Summertree Animal Clinic; Dr. Lisa Newell of Malibu Coast Animal Clinic; and my therapists at the North Texas Animal Rehabilitation Center, Jennie Ralph and Rich Mysliwiec.

Introduction

A Blindside Hit

Just a few months ago, my whole world was rattled, its axis visibly wobbled. My best friend Olivera fourteen-year-old mixed breed that we rescued as a puppy from a no-kill sheltertumbled down an embankment at our mountain retreat in California and never regained his footing, instantly paralyzed in his hind quarters. Ollies medical history was already complex, to say the leasthaving suffered two nearly lethal bouts with a rogue immune system that attacked first the clotting agents in his blood and then his neuromuscular connections. In the past year, rapidly advancing cataracts had left him almost completely blind.

But Oliver is one tough guy. Weighing in at only twenty pounds, our boy had managed to stave off his own traitorous immune system with enough steroids to disqualify him from the Baseball Hall of Fame. And Ollie had learned that his eyes were not the most critical connection to his brain or his quality of life. He had adjusted well to Hamlets oft-quoted description of life as the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to and had entered canine old age with a certain measure of dignity and class.

This time was different, however. We rushed Oliver back to our home in Dallas, only to discover that the paralysis had become the least of our problems, as Ollie was also diagnosed with pyothorax (an often fatal lung disease) as well as what was suspected to be cancer in his chest. In the brief span of a few days, things went from bad to worse to the unthinkable. Oliver was catapulting down a medical abyss, and I was tumbling with him. While I knew full well that Ollie was approaching the last phase of a long life, I had always assumed that his final days would be just as graceful and dignified as the rest of his life had been. I never imagined that the end would come in a rush of trauma and disease that seemed to be spinning out of control. I was caught totally off guard by this blindside hit.

Soon I was shuttling back and forth twice a day between our home and the veterinary intensive care unit, praying for just paralysis in his hind legs. I was prepared to exchange permanent paralysis for short-term survival, if only there were some way that I could close the deal on this compromisea final hurdle that rarely eluded me in my life as a businessman. But that deal wasnt on the table. Instead, I heard words like cremation and the merciful thing to do in conferences where the vets dragged out the time-worn adage that I should hope for the best, but prepare for the worst. I was even down to the point of walking our property in search of a final resting place for the boy we fondly referred to as our clan leader. The first in a progression of six canines that eventually arrived on the scene, Oliver was a natural alpha, bonding first to his two human parentsthe ultimate alpha male and femaleand never relinquishing his leadership position to any of the five younger canines that we assembled around him over the years.

Once Oliver had been absent for a few days during his stay in intensive care, our other dogs began to move in somewhat erratic and undisciplined directions, as if the steering column of a five-wheeled vehicle had come unhinged and the tires just rolled off in random directions unconnected to one another. The normal rhythm and melody of the clan was disrupted and cacophonous, resembling a collection of orchestral instruments warming up before that moment of silence when the maestro finally takes the podium, baton in hand. Olivers first lieutenant Elmer (age thirteen) was particularly lost without his only older brother. Elmer and Oliver were exceptionally devoted to each other, usually napping in the same dog bed lying back to back, just barely touching along their spines but comforted by the warmth of each others bodies. Without Oliver to lean on, Elmer paced around endlessly, aware that something was amiss; Oliver had simply been gone too long. And my sense of things being off kilter was palpable as well: I was obsessed with the thought of losing Oliver at any moment. Dogs are incredibly adept at sensing a shift in their masters moods, and I have no doubt that I was emitting to the clan a profound sense of angst in a silent language that was clearly understood by all.

Oliver was not the only member of the family who had been through the revolving door of an array of doctors offices and hospitals. I had experienced my own labyrinth of medical tunnels: epileptic seizures, diagnosed brain cancer, heart disease, three operations to install a series of pacer-defibrillators in my chest, and hundreds of episodes of atrial fibrillation. But I had always managed to emerge from the tunnel and, in the process, had eventually learned to accept the fact that death inevitably follows life. That is one of the few benefits of engaging in a series of health crises that pose the risk of an untimely death. Once I had survived the first battle and then another one or two, I became a bit more philosophicalsome might even say cockyabout meeting that dragon the next time around. And sure enough, there was always another time around. After a while, I began to think not in terms of avoiding death but rather of experiencing a good deathan exit that was postponed long enough to be well-timed and one that was shielded from the more gruesome declines that may ravage our bodies or rob our minds on the way out.

In an effort to stave off the panic that might otherwise have engulfed my family in the midst of one of my medical battles, I learned how to remain calm and strongor at the very least how to do a good imitation of someone who was calm and strong. I refused to allow a sense of dread to seep out of my pores and infect my wife, Candice, or any of our three daughters. I was always the strong one, but I was never my own best friend... Oliver was my best friend.

The bond between a man and his dog has often been described as unconditional, as if the absence of conditions is at the heart of what distinguishes this love from any other. But unconditional

Next page