EPILOGUE

I step out of the white Mercedes van and the driver opens my door and hands me my suitcase. The hotel is as I remember it, built into the side of the hill like a natural addition to the landscape. My room is large and comfortable and I walk to the patio overlooking the town and the sea far below and I cast my eyes up the hill and across until they settle on the Cortino house.

I wonder who lives in it now. It has been six years since the bodies of Cortino, his invalid wife, and his bodyguard were found murdered in their bedroom on an early June morning. The crime slapped the sleepy town awake, sent it reeling, but the passage of time and the endless lapping of the ocean on its doorstep gently nudged the town back to sleep. I imagine the doors of the houses high up on the hill are locked at night now.

The city of Los Angeles had a similar reaction the second time a nominee was assassinated while in its care. But there was no Sirhan Sirhan to exact revenge upon, just a John Smith with a nondescript face and a pleasant voice and an ability to vanish into thin air. Two years later, the case remains unsolved, despite every effort to gain some answers.

I am here in Positano getting my mind right. It is late summer and I informed Mr. Ryan I would need a few months between assignments this time. A few months without making connections, without severing connections, just a few months to breathe and live and remember.

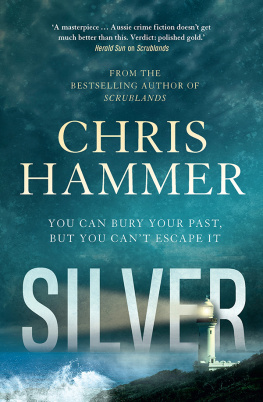

I have worked exclusively in Europe since the Abe Mann killing, and Mr. Ryan moved to Paris to facilitate his role in my work. He has found the move from the desert to be agreeable, the law enforcement here more relaxed, the economy strong, the supply of contracts endless. I believe he is happy having a Silver Bear under his aegis, though we dont talk about personal things. Ours is a business relationship, and things are simple.

He traveled recently to Denver, Colorado, upon my request. It is the first time he has made a file on a person who wasnt a target. I have the file in my hand now, but I havent opened it. I was waiting until I arrived in this place, this town built into the side of a hill yearning to tumble into the sea. I sit heavily on a patio chair, breathe in the cool night air, and place my thumb under the seal.

The name at the top of the page is Jacqueline Grant, formerly Jake Owens of Boston, Massachusetts. The surveillance photo shows a profile of a woman stepping out of a car, hurrying across a parking lot to a grocery store. Her hair is longer than it was when I knew her and her face is a bit fuller. She looks content, or maybe Im projecting this on to her image.

She has been married for three years. Her husband owns a restaurant. A clean, well-lighted place that serves hamburgers to locals. He is her age and treats her well. I wonder how they met. I wonder if she was unlucky with men after I kicked her in the stomach or if she swore them off until Alex Grant came into her life. I wonder if he was safe and she felt secure with him.

I wonder if she loves him.

CHAPTER 1

THE last day of the cruelest month, and appropriately it rains. Not the spring rain of new life and rebirth, not for me. Death. In my life, always death. I am young; if you saw me on the street, you might think, What a nice, clean-cut young man. Ill bet he works in advertising or perhaps a nice accounting firm. Ill bet hes married and is just starting a family. Ill bet his parents raised him well. But you would be wrong. I am old in a thousand ways. I have seen things and done things that would make you rush instinctively to your childs bedroom and hug him tight to your chest, breathing quick in short bursts like a misfiring engine, and repeat over and over, Its okay, baby. Its okay. Everythings okay.

I am a bad man. I do not have any friends. I do not speak to women or children for longer than is absolutely necessary. I groom myself to blend, like a chameleon darkening its pigment against the side of an oak tree. My hair is cut short, my eyes are hidden behind dark glasses, my dress would inspire a yawn from anyone who passed me in the street. I do not call attention to myself in any way.

I have lived this way for as long as I can remember, although in truth it has only been ten years. The events of my life prior to that day, I have forgotten in all detail, although I do remember the pain. Joy and pain tend to make imprints on memory that do not dim, flecks of senses rather than images that resurrect themselves involuntarily and without warning. I have had precious little of the former and a lifetime of the latter. A week ago, I read a poll that reported ninety percent of people over the age of sixty would choose to be a teenager again if they could. If those same people could have experienced one day of my teenage years, not a single hand would be counted.

The past does not interest me, though it is always there, just below the surface, like dangerous blurs and shapes an ocean swimmer senses in the deep. I am fond of the present. I am in command in the present. I am master of my own destiny in the present. If I choose, I can touch someone, or let someone touch me, but only in the present. Free will is a gift of the present; the only time I can choose to outwit God. The future, your fate, though, belongs to God. If you try to outsmart God in planning your fate, you are in for disappointment. He owns the future, and He loves O. Henry endings.

The present is full of rain and bluster, and I hurry to close the door behind me as I duck into an indiscriminate warehouse alongside the Charles River. It has been a cold April, which many say indicates a long, hot summer approaching, but I do not make predictions. The warehouse is damp, and I can smell mildew, fresh-cut sawdust, and fear.

People do not like to meet with me. Even those whom society considers dangerous are uneasy in my presence. They have heard stories about Singapore, Providence, and Brooklyn. About Washington, Baltimore, and Miami. About London, Bonn, and Dallas. They do not want to say something to make me uncomfortable or angry, and so they choose their words with precision. Fear is a feeling foreign to these types of men, and they do not like the way it settles in their stomach. They get me in and out as fast as they can and with very little negotiation.

Presently, I am to meet with a black man named Archibald Grant. His given name is Cotton Grant, but he didnt like the way Cotton made him sound like a Georgia hillbilly Negro, so he moved to Boston and started calling himself Archibald. He thought it made him sound aristocratic, like he came from prosperity, and he liked the way it sounded on a whores lips: Archibald, slide on over here in a soft falsetto. He does not know that I know about the name Cotton. In my experience, it is best to know every detail about those with whom you are meeting. A single mention of a surprising detail, a part of his life he thought was buried so deep as to never be found, can cause him to pause just long enough to make a difference. A pause is all I need most of the time.

I walk through a hallway and am stopped at a large door by two towering black behemoths, each with necks the size of my waist. They look at me, and their eyes measure me. Clearly, they were expecting something different after all theyve been told. I am used to this. I am used to the disappointment in some of their eyes as they think, Give me ten minutes in a room with him and well see whats shakin. But I do not have an ego, and I avoid confrontations.

You be? says the one on the right whose slouch makes the handle of his pistol crimp his shirt just enough to let me know its there.