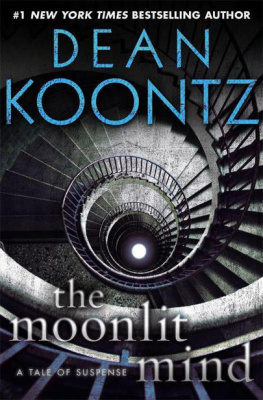

Dean Koontz

The Moonlit Mind

Crispin lives wild in the city, a feral boy of twelve, and he has no friend but Harley, though Harley never speaks.

Friendship does not depend on conversation. Sometimes the most important communication is not mouth to ear, but heart to heart.

Harley cant speak because he is a dog. He understands many words, but he isnt able to form them. He can bark, but he does not. Neither does he growl.

Silence is to Harley as music to a harp, flowing from him in glissando passages and arpeggios that are melodious to Crispin. The boy has heard too much in his few years. Quiet is a symphony to him, and the profound silence in any hushed place is a hymn.

This metropolis, like all others, is an empire of noise. The city rattles, bangs, and thumps. It buzzes and squeals, hisses and roars. Honks, clangs, tolls, jingles, clicks, clacks, creaks, knocks, pops, and rumbles.

Even in this storm of sound, however, quiet havens exist. Across the vast lawns of St. Mary Salome Cemetery, between tall pines and cedars like processions of robed monks, concentric circles of granite headstones lead inward to open-air mausoleum walls where the ashes of the dead are interred behind bronze plaques. The eight-foot-high, freestanding walls are arranged like spokes in a wheel. On any windless night, the massive evergreens of St. Mary Salome muffle the municipal voice, and the wheel of walls baffles it entirely.

At the hub where the spokes meet lies a wide circle of grass and at its center a great round slab of gray granite that serves as a bench. Here, Crispin sometimes sits in moonlight until the silence soothes his soul.

Then he and Harley move to the grass, where the boy prepares his bedroll. With no guilt to claw at his conscience, the dog sleeps the sleep of an innocent. The boy is not so fortunate.

Crispin suffers nightmares. They are based on memories.

Harley seems to dream of running free, toes spreading and paws trembling as he races across imagined meadows. He does not whimper but makes small thin sounds of delight.

Once, when the boy was ten, he woke well past midnight and saw the silvery shimmering form of a woman in a long dress or robe. She approached between two mausoleum walls, seeming not to walk but rather to glide like a skater on ice.

Crispin sat up, frightened because the woman had no substance. Moonlit objects behind her were visible through her.

She neither smiled nor threatened. Her expression was solemn.

She drifted to a stop about two yards from them, her bare feet a few inches above the grass. For a long moment, she gazed upon them.

Crispin felt that he should speak to her. But he could not.

Although the boy only half rose, Harley stood on all fours. Clearly, the dog saw the woman, too. His tail wagged.

When she moved past them, Crispin caught the scent of perfumed ointment. Harley sniffed with what seemed to be pleasure.

The woman evaporated as if she were a fog phantom encountering a warm current of air.

Crispin first thought she must be a ghost haunting these fields of graves. Later he wondered if hed witnessed instead a visitation, the spirit of Saint Mary Salome, for whom the cemetery was named.

Over the past three years, since he was nine, the boy has lived in this city by his wits and by his daring. He has enjoyed little human companionship or charity.

He doesnt spend every night in the cemetery. He sleeps in many places to avoid following a routine that might leave him vulnerable to discovery.

In places more ordinary than cemeteries, he and the dog often see extraordinary things. Not all their discoveries are supernatural. Most are as real as sunlight and starlight, and some of those things are more terrible than any ghost or goblin could be.

This city perhaps any city is a place of secrets and enigmas. Roaming alone with your dog in realms that others seldom visit, you will glimpse disturbing phenomena and strange presences that suggest the world has dimensions that reason alone cannot explain.

The boy is sometimes afraid, but never the dog.

Neither of them is ever lonely. They are family to each other, but more than family. They are each others salvation, each a lamp by which the other finds his way.

Harley was abandoned to the streets. No one but the boy loves this mixed-breed canine, which appears to be half golden retriever and half mystery mutt.

Crispin was not abandoned. He escaped.

And he is hunted.

Three years earlier

Crispin, only nine years old, is two days on the run, having fled a scene of intolerable horror on a night in late September. He has no one to whom he can turn. Those who should be trustworthy have already proven to be evil and to be intent on his destruction.

Of the eleven dollars in his possession when he escaped, he now has only four. He has spent the rest on food and drink purchased from vendors with street-corner carts.

The previous night, he slept in a nest of shrubbery in Statler Park, too exhausted to be fully wakened even by the occasional sirens of passing police cars or, near dawn, by the racket of sanitation workers emptying park trash cans into their truck.

On Monday he spends a couple of the daylight hours visiting the library. The stacks are a maze in which he can hide.

He is too much in the grip of fear and grief to be able to read. Now and then he pages through big glossy travel books, studying the photos, but he has no way of getting to those far, safe places. The childrens picture books that once amused him no longer seem at all funny.

For a while he walks along the banks of the river, watching a few fishermen. The water is gray under a blue sky, and the men seem gray, too, sad and listless. The fish are not biting.

Most of the day he wanders alleyways where he thinks he is less likely to encounter those who are surely looking for him. Behind a restaurant, a kitchen worker asks why he isnt in school. No good lie occurs to him, and he runs from her.

The day is mild, as were the previous day and night, but suddenly it grows cool and then cooler in the late afternoon. He is wearing a short-sleeved shirt, and the gooseflesh on his bare arms may or may not be caused by the chilly air.

In a vacant lot between a drugstore and a marshal-arts dojo, a Goodwill Industries collection bin overflows with used clothing and other items. Rummaging among those donations, Crispin finds a gray wool sweater that fits him.

He takes also a dark-blue knitted toboggan cap. He pulls it low over his forehead, over the tops of his ears.

Perhaps a nine-year-old boy alone will only call attention to himself by such an effort at disguise. He suspects that the simple cap is, on him, flamboyant. He feels clownish. But he does not strip it off and toss it away.

He has walked so many alleys and serviceways, has darted across so many avenues into so many shadowed backstreets, that he has become not merely lost but also disoriented. The walls of buildings appear to tilt toward or away from him at precarious angles. The cobblestone pavement under his feet resembles large reptilian scales, as though he is walking on the armored back of a sleeping dragon.

The city, always large, seems to have become an entire world, as immense as it is hostile.

With the disorientation comes a quiet desperation that compels Crispin at times to run when he knows full well that no one is in immediate pursuit of him.

Shortly before dusk, in a wide alleyway that serves ancient brick warehouses with stained-concrete loading docks, he encounters the dog. Golden, it approaches along the east side of the passage, in a slant of light from the declining sun.

The dog stops before Crispin, gazing up at him, head cocked. In the last bright light of day, the animals eyes are as golden as its coat, pupils small and irises glowing.