Swords and Deviltry

by Fritz Leiber

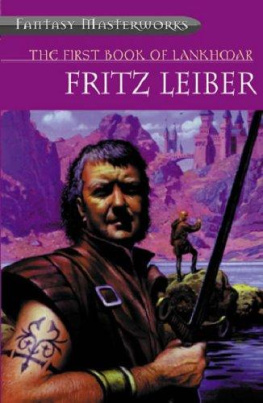

Sundered from us by gulfs of time and stranger dimensions dreams the ancient world of Nehwon with its towers and skulls and jewels, its swords and sorceries. Nehwon's known realms crowd about the Inner Sea: northward the green-forested fierce Land of the Eight Cities, eastward the steppe-dwelling Mingol horsemen and the desert where caravans creep from the rich Eastern Lands and the River Tilth. But southward, linked to the desert only by the Sinking Land and further warded by the Great Dike and the Mountains of Hunger, are the rich grain fields and walled cities of Lankhmar, eldest and chiefest of Nehwon's lands. Dominating the Land of Lankhmar and crouching at the silty mouth of the River Hlal in a secure corner between the grain fields, the Great Salt Marsh, and the Inner Sea is the massive-walled and mazy-alleyed metropolis of Lankhmar, thick with thieves and shaven priests, lean-framed magicians and fat-bellied merchants Lankhmar the Imperishable, the City of the Black Toga.

In Lankhmar on one murky night, if we can believe the runic books of Sheelba of the Eyeless Face, there met for the first time those two dubious heroes and whimsical scoundrels, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Fafhrd's origins were easy to perceive in his near seven-foot height and limber-looking ranginess, his hammered ornaments and huge longsword: he was clearly a barbarian from the Cold Waste north even of the Eight Cities and the Trollstep Mountains. The Mouser's antecedents were more cryptic and hardly to be deduced from his childlike stature, gray garb, mouseskin hood shadowing flat swart face, and deceptively dainty rapier; but somewhere about him was the suggestion of cities and the south, the dark streets and also the sun-drenched spaces. As the twain eyed each other challengingly through the murky fog lit indirectly by distant torches, they were already dimly aware that they were two long-sundered, matching fragments of a greater hero and that each had found a comrade who would outlast a thousand quests and a lifetime or a hundred lifetimes of adventuring.

No one at that moment could have guessed that the Gray Mouser was once named Mouse, or that Fafhrd had recently been a youth whose voice was by training high-pitched, who wore white furs only, and who still slept in his mother's tent although he was eighteen.

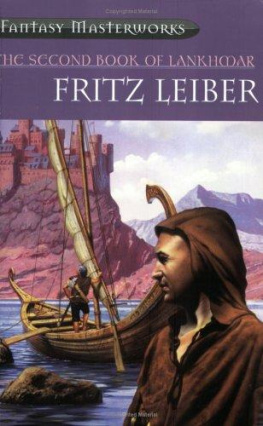

At Cold Corner in midwinter, the women of the Snow Clan were waging a cold war against the men. They trudged about like ghosts in their whitest furs, almost invisible against the new-fallen snow, always together in female groups, silent or at most hissing like angry shades. They avoided Godshall with its trees for pillars and walls of laced leather and towering pine-needle roof.

They gathered in the big, oval Tent of the Women, which stood guard in front of the smaller home tents, for sessions of chanting and ominous moaning and various silent practices designed to create powerful enchantments that would tether their husbands ankles to Cold Corner, tie up their loins, and give them sniveling, nose-dripping colds, with the threat of the Great Cough and Winter Fever held in reserve. Any man so unwise as to walk alone by day was apt to be set upon and snowballed and, if caught, thrashed be he even skald or mighty hunter.

And a snowballing by Snow Clan women was nothing to laugh at. They threw overarm, it is true, but their muscles for that had been greatly strengthened by much splitting of firewood, lopping of high branches, and pounding of hides, including the iron-hard one of the snowy behemoth. And they sometimes froze their snowballs.

The sinewy, winter-hardened men took all of this with immense dignity, striding about like kings in their conspicuous black, russet, and rainbow-dyed ceremonial furs, drinking hugely but with discretion, and trading as shrewdly as Ilthmarts their bits of amber and ambergris, their snow-diamonds visible only by night, their glossy animal pelts, and their ice-herbs, in exchange for woven fabrics, hot spices, blued and browned iron, honey, waxen candles, firepowders that flared with a colored roar, and other products of the civilized south. Nevertheless, they made a point of keeping generally in groups, and there was many a nose a-drip among them.

It was not the trading the women objected to. Their men were good at that and they the women were the chief beneficiaries. They greatly preferred it to their husbands occasional piratings, which took those lusty men far down the eastern coasts of the Outer Sea, out of reach of immediate matriarchal supervision and even, the women sometimes feared, of their potent female magic. Cold Corner was the farthest south ever got by the entire Snow Clan, whose members spent most of their lives on the Cold Waste and among the foothills of the untopped Mountains of the Giants and the even more northerly Bones of the Old Ones, and so this midwinter camp was their one yearly chance to trade peaceably with venturesome Mingols, Sarheenmarts, Lankhmarts, and even an occasional Eastern desert-man, heavily beturbaned, bundled up to the eyes, and elephantinely gloved and booted.

Nor was it the guzzling which the women opposed. Their husbands were great quaffers of mead and ale at all times and even of the native white snow-potato brandy, a headier drink than most of the wines and boozes the traders hopefully dispensed.

No, what the Snow Women hated so venomously and which each year caused them to wage cold war with hardly any material or magical holds barred, was the theatrical show which inevitably came shivering north with the traders, its daring troupers with faces chapped and legs chilblained, but hearts a-beat for soft northern gold and easy if rampageous audiences a show so blasphemous and obscene that the men preempted Godshall for its performance (God being unshockable) and refused to let the women and youths view it; a show whose actors were, according to the women, solely dirty old men and even dirtier scrawny southern girls, as loose in their morals as in the lacing of their skimpy garments, when they went clothed at all. It did not occur to the Snow Women that a scrawny wench, her dirty nakedness all blue goosebumps in the chill of drafty Godshall, would hardly be an object of erotic appeal, besides her risking permanent all-over frostbite.

So the Snow Women each midwinter hissed and magicked and sneaked and sniped with their crusty snowballs at huge men retreating with pomp, and frequently caught an old or crippled or foolish, young, drunken husband and beat him soundly.

This outwardly comic combat had sinister undertones. Particularly when working all together, the Snow Women were reputed to wield mighty magics, particularly through the element of cold and its consequences: slipperiness, the sudden freezing of flesh, the gluing of skin to metal, the frangibility of objects, the menacing mass of snow-laden trees and branches, and the vastly greater mass of avalanches. And there was no man wholly unafraid of the hypnotic power in their ice-blue eyes.

Each Snow Woman, usually with the aid of the rest, worked to maintain absolute control of her man, though leaving him seemingly free, and it was whispered that recalcitrant husbands had been injured and even slain, generally by some frigid instrumentality. While at the same time witchy cliques and individual sorceresses played against each other a power game in which the brawniest and boldest of men, even chiefs and priests, were but counters.

During the fortnight of trading and the two days of the Show, hags and great strapping girls guarded the Tent of the Women at all quarters, while from within came strong perfumes, stenches, flashes and intermittent glows by night, clashings and tinklings, cracklings and quenchings, and incantational chantings and whisperings that never quite stopped.