Ramsey Campbell

The Inhabitant of the Lake and Less Welcome Tenants

When I Was Ten Years Old I Discovered H. P. Lovecraft In The Color out of Space, and was profoundly excited and disturbed by his work, and some years later, after I had read considerably more of Lovecrafts fiction, I turned a bent for writing which began when I was seven toward the Cthulhu Mythos. I wrote five stories in nine months; they were little more than amateurish pastiches of Lovecrafts tales, but I had courage enough to show some of them to August Derleth, and, had he not considered them promising and encouraged me to carry on, those tales might have remained in the original draft.

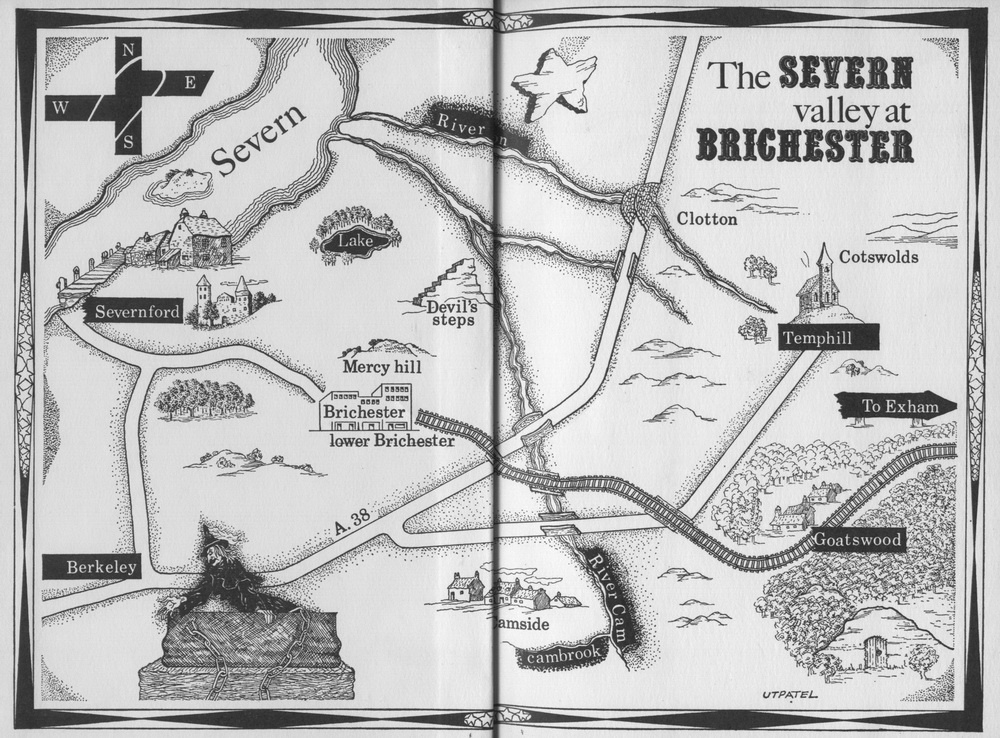

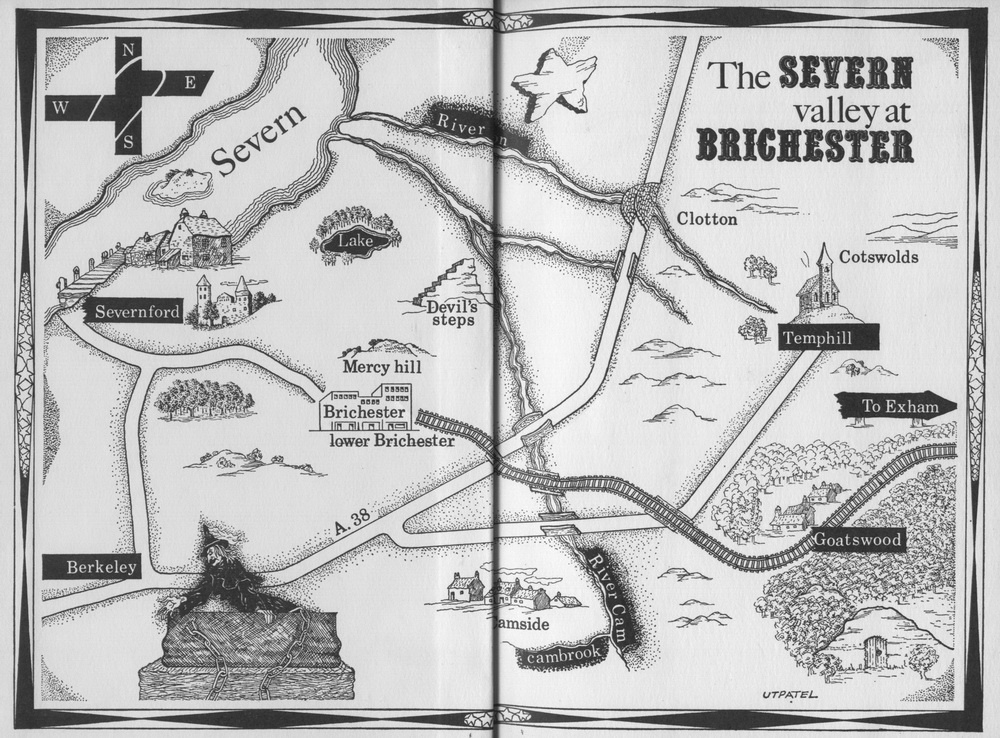

Perhaps even more important, he persuaded me to agree that the Arkham country had been saturated as setting for stories in the Mythos, and that a new milieu for a series of tales might well be originated in Great Britain. He felt certain that even H. P. Lovecraft would approve of such a new setting, and of a sequence of stories taking place there. I considered the Severn Valley a likely milieu. As a Roman-occupied area, it might retain influences of the decadent Roman practises; and some years ago, in the Cotswolds, a supposed witch was executed by persons unknown. With cautious enthusiasm, I set about creating my own towns. Some research was, of course, necessary, and the various towns were not conceived as a whole; their details were added to in each story and so the towns came into being.

Among the stories thus far written, there are six towns in the area. They do not correspond to the settlements in the Arkham country, except insofar as they represent a conscious attempt to parallel Lovecrafts Massachusetts towns; they are primarily my attempt to invent a realistic, detailed background to aid in imparting verisimilitude to my fiction.

Brichester (the Roman 'chestercastrawith a likely prefix) is the most important of these towns. A large modern city, complete with central office buildings, cinemas, stores, and the like, it yet has its regions of alien influence. It is composed of three sections: Mercy Hill, a raised portion of the town, at the top of which stands a hospital a one-time prison, while some miles beyond it lies a terribly haunted lake; Central Brichester, an area of offices and large stores; and Lower Brichester, where most trains arrive. In itself, it is a perfectly normal town, and most of the sorcerers living there practise their arts secretly (although there still is a regrettable cult among students at the university), illustrating how underground societies exist in every community.

Camside, on the bank of the river Cam, is a rather unimportant town between Berkeley and Severnford, once visited by a man intent on seeking out the god Byatis, but otherwise undistinguished. Severnford is part dockland, its buildings mostly shabby and dilapidated, including a cinema and several public-houses; beyond it is an island reputedly used as a meeting place for covens. At the center a group of historic buildings is preserved, among them an inn now closed because of vandalism.

The remaining towns of the Severn Valley at Brichester are rather less than normal. Clotton (a corruption of Cloth Town) is inhabited by unusually superstitious people. In 1931 it was invaded by malefic aliens. Once a fairly large settlement, Clotton is today too small to appear on most maps, and is widely supposed to be haunted, and is thus much avoided.

Temphill (Temple Hill a reference to the towns being built around a church reported to be other-dimensional) is the only town which is rather completely mapped. It is a small settlement with only one hotel. Most of its buildings are neglected, and its inhabitants seem more interested in old ways, in magic and the outre, than in normal, prosaic life. Temphill is built on a long main road, different portions of which are known under different names Wood Street, South Street, etc. ; it crosses a river, and toward the center of town rises to a hill on which is built the famous shunned church.

Finally, there is Goatswood, the town lying furthest into the Cotswolds. Surrounded by woods, this town contains a little-used railway station and a fairly modern town center; but its inhabitants are reputed to be non-human. Goatswood takes its name from the legend that the god Shub-Niggurath is either imprisoned or has at times made his home in a hill near the town.

Like most other writers who have ventured to add to Lovecrafts Cthulhu Mythos, I also invented esoteric volumes to which references could be made. One, The Revelations of Glaaki, was written by members of a cult under the inspiration of the god they worshipped; it was subsequently published in an edition from which many of the more unconventional passages had been cut, now a very rare volume. The other, an untitled and much-banned work by Johannes Pott, was rejected violently by publishers in Jena, circulated in handwritten copies among underground groups, and has never been printed. It contains many repulsive and shocking concepts, among the mildest of which is the theory that all areas of darkness are inhabited by malformed beings.

The reader will notice that I have frequently resorted to cross- references, not only of settings, but also of events. The reader will observe also that I have not directly utilized the beings of the Lovecraft pantheon, I have but referred to them; for I wished to invent my own, or to clarify inexplicit hints left by Lovecraft and other contributors to the Mythos; I wanted, in sum, to add to the Mythos. I hope that readers of this book will find it possible to conclude that in their own modest way these stories reflect the greater wonder and horror of the masterpieces of H. P. Lovecraft.

J. Ramsey Campbell

Liverpool, England

7 January 1964

Is it some lurking remnant of the elder world in each of us that draws us towards the beings which survive from other aeons? Surely there must be such a remnant in me, for there can be no sane or wholesome reason why I should have strayed that day to the old, legend-infected ruin on the hill, nor can any commonplace reason be deduced for my finding the secret underground room there, and still less for my opening of the door of horror which I discovered.

It was on a visit to the British Museum that I first heard of the legend which suggested a reason for the general avoidance of a hill outside Brichester. I had come to the Museum in search of certain volumes preserved there not books of demonic lore, but extremely scarce tomes dealing with the local history of the Severn valley, as visualised in retrospect by an 18th-century clergyman. A friend who lived in the Camside region near Berkeley had asked me to look up some historical facts for his forthcoming article in the Camside Observer, which I could impart to him when I began my stay with him that weekend, since he was ill and would not be capable of a London visit for some time. I reached the Museum library with no thoughts other than that I would quickly check through the requisite volumes, note down the appropriate quotations and leave in my car for my destination straight from the Museum.

Upon entering the lofty-ceilinged room of carefully tended books, I found from the librarian that the volumes I wished to study were at that moment in use, but should soon be returned, if I cared to wait a short time. To spend this time, I was not interested in referring to any historical book, but instead asked the keeper of the volumes to allow me to glance through the Museum's copy of the almost unobtainable Necronomicon. More than an hour passed in reading it, as best I 'could. Such suggestions concerning what may lie behind the tranquil facade of normality are not easily dismissed from the mind; and I confess that as I read of the alien beings which, according to the author, lurk in dark and shunned places of the world, I found myself accepting what I read as reality. As I pressed deeper into the dark mythos which surrounds those terrors from beyond bloated Cthulhu, indescribable Shub-Niggurath, vast batrachian Dagon I might have been sucked into the whirlpool of absolute belief, had my engrossment not been interrupted by the librarian, bearing an armful of yellowed volumes.