Nick Cole

THE WASTELAND SAGA

THREE NOVELS

Old Man and the Wasteland

The Savage Boy

The Road is a River

PART I

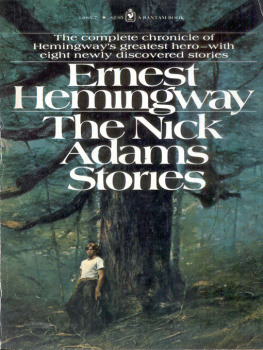

The Old Man and the Wasteland

It was dark when he stepped outside into the cool air. Overhead the last crystals of night faded into a soft blue blanket that would precede the dawn. Through the thick pads of his calloused feet he could feel the rocky, cracked, cold earth. He would wear his huaraches after he left and was away from the sleeping village.

He had not slept for much of the night. Had not been sleeping for longer than he could remember. Had not slept as he did when he was young. The bones within ached, but he was old and that was to be expected.

He began to work long bony fingers into the area above his chest. The area that had made him feel old since he first felt the soreness that was there. The area where his satchel would push down as he walked.

He thought about tea, but the smoke from the mesquite would betray him as would the clatter of his old blue percolator and he decided against it.

He stepped back inside the shed, looked around once, taking in the cot, patched and sagging, the desk and the stove. He went to the desk and considered its drawers. There was nothing there that should go in his satchel. He would need only his tools. His crowbar, his worn rawhide gloves, his rope, the can of pitch, the tin of grease and his pliers. Not the book.

But if I die. If I go too far or fall into a hole. If my leg is broken then I might want the book.

He dismissed those thoughts.

If you die then you cant read. If you are dying then you should try to live. And if it is too much, that is what the gun is for. Besides, youve read the book already. Many times in fact.

He put the book back in its place.

He went to the shelf and opened the cigar box that contained the pistol. He loved the box more than the gun inside. The picture of the sea, the city, and the waving palms on the front reminded him of places in the book. Inside the box, the gun, dull and waiting along with five loose shells, an evil number, rattled as his stiff fingers chased them across the bottom.

Moving quickly now he took the old blue percolator and rolled it into the thin blanket that lay on the cot. He stuffed them both inside the worn satchel, reminding him of the books description of the furled sail. Patched with flour sacks it looked the flag of permanent defeat. He shouldered the bag quickly and chased the line away telling himself he was thinking too much of the book and not the things he should be. He looked around the shed once more.

Come back with something. And if not, then goodbye.

He passed silently along the trail that led through the village. To the west, the field of broken glass began to glitter like fallen stars in the hard-packed red dirt as it always did in this time before the sun.

At the pantry he took cooked beans, tortillas, and a little bit of rice from the night before. The village would not miss these things. Still they would be angry with him. Angry he had gone. Even though they wished he would because he was unlucky.

Salao. In the book unlucky is Salao. The worst kind.

The villagers say you are curst.

He filled his water bottle from the spring, drank a bit and filled it again. The water was cold and tasted of iron. He drank again and filled it once more. Soon the day would be very hot.

At the top of the small rise east of the village he looked back.

Forty years maybe. If my count has been right.

It was an old processing plant by the side of the highway east of what was once Yuma. It was rusting in the desert before the bombs fell, now it was the market and pantry of the village. Its outlying sheds the houses of the villagers, his friends and family. He tried to see if smoke was rising yet from his sons house. But his daughter-in-law would be tired from the new baby.

So maybe she is still sleeping.

If his granddaughter came running out, seeing him at the top of the rise against the dawn, he would have to send her back. He was going too deep into the wasteland today.

Too dangerous for her.

Even though she knows every trick of salvage?

I might need her. What if I find something big?

I may not be as strong as I think, but I know many tricks and I have resolution.

My friend in the book would say that, yes.

He would send her back. It was too dangerous. He adjusted the strap wider on his shoulder to protect the area above his heart where the satchel always bit, then turned and walked down the slope away from the village and into the wasteland.

He sang bits of a song he knew from Before. Years hid most of the lyrics and now he wanted to remember when he first heard the song. As if the memory would bring back the lost words hed skipped over.

Time keeps its secrets. Not like this desert. Not like the wasteland.

In the rising sun, his muscles began to loosen as his stride began to lengthen, and soon the ache was gone from his bones. His course was set between two peaks none of the village had ever bothered to name after the cataclysm. Maybe once someone had a name for them. Probably on charts and rail survey maps of the area once known as the Sonoran Desert. But such things had since crumbled or burned up.

And what are names? He once had a name. Now the villagers simply called him the Old Man. It seemed appropriate. Often he responded.

At noon he stopped for the cool water in the bottle kept beneath the blanket in his satchel. Still mumbling the words of the song among the silent broken rocks, he drank slowly. He had reached the saddle between the two low hills.

Where had he first heard the song? he wondered.

Below, the bowl of the wasteland lay open and shimmering. On the far horizon, jagged peaks; beyond those, the bones of cities.

For seventy-eight days the Old Man had gone west with the other salvagers, heading out at dawn with hot tea con leche and sweet fry bread. Walking and pulling their sleds and pallets. In teams and sometimes alone. For seventy-eight days the Old Man had gone out and brought back nothing.

My friend in the book went eighty-six days. Then he caught the big fish. So I have a few days to go. I am only seventy-eight days unlucky. Not eighty-six. That would be worse.

Every canyon silent, every shed searched, every wreck empty. It was just bad luck the others said. It would turn. But in the days that followed he found himself alone for most of the day. If he went down a road, keeping sight of the other teams, they would soon be lost from view. At noon he would eat alone in the shade of a large rock and smell on a sudden breeze their cookfires. He missed those times, after the shared lunch, the talk and short nap before they would start anew at what one had found, pulling it from the earth, extracting it from a wreck, hauling it back to the village. Returning after nightfall as the women and children came out to see this great new thing they could have back. This thing that had been rescued from the time Before and would be theirs in the time of Now. Forty years of that, morning, noon, and night of salvage. It was good work. It was the only work.

Until he found the hot radio.

His first years of salvage were of the things that had built the village. On early nights when the salvagers returned and light still hung in the sky, he could walk through the village and see the things he had hauled from the desert. The door on his sons house that had once been part of a refrigerator from a trailer he and Big Pedro had found south of the Great Wreck. The trailer someone had been living in after the bombs. There were opened cans, beer, and food inside the trailer. Cigarette butts in piles. That had been fifteen years after the war. But when they opened the door it was silent and still. An afternoon wind had picked up and the trailer rocked in the brief gusts that seem to come and go as if by their own choosing. Big Pedro did not like such places. The Old Man never asked the why of how someone salvaged. He accepted this of Pedro and together theyd worked for a time.