To Al, Rachel, and Julia.

Again. Always.

It has always pleased me to exalt plants in the scale of organized beings.

CHARLES DARWIN

It is not clear that intelligence has any long-term survival value.

STEPHEN HAWKING

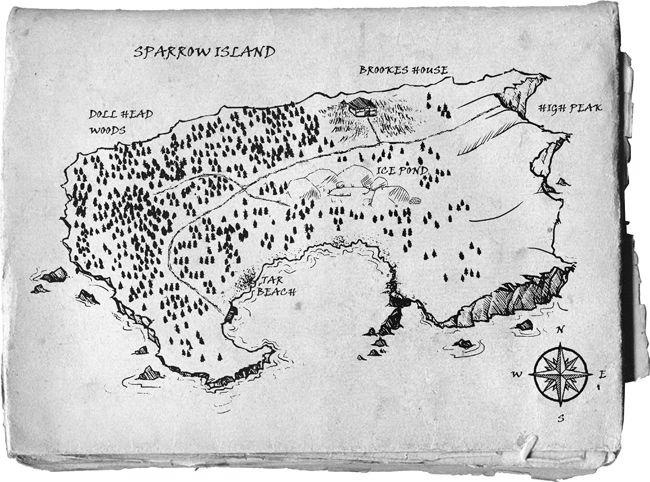

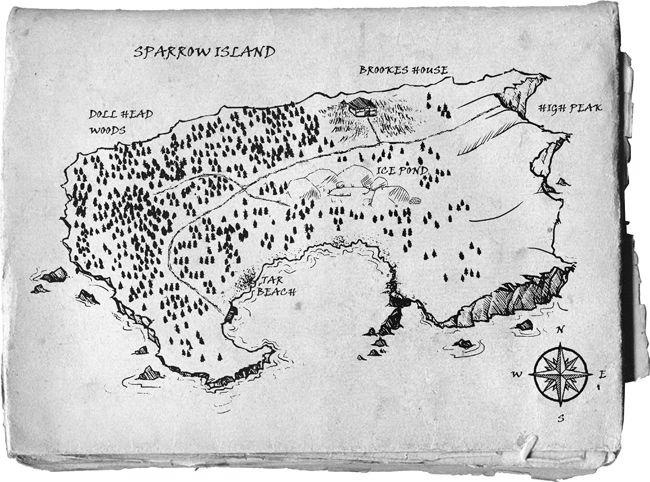

SPARROW ISLAND LIES FIFTY MILES off the coast of Nova Scotia, where icy winters and frequent storms make it a brutal spot for life to survive. On one side, soaring cliffs act as a natural barrier against the Atlantic, protecting the rest of the island from invading winds and pounding surf. Along these scabrous cliffs, only the hardiest plants take root. Winter creepers, juniper, and heather cling stubbornly low to the ground, pugnacious against the elements. The other side of the island is flat with dense woods, sixty acres of knobby pines and twisted deciduous trees that huddle together like souls on a life raft.

Seventy-two-year-old George Brookes, the only resident of the island, seemed remarkably fit for such a harsh place. He ran fiercely through the frigid woods, dodging fallen branches as his bare feet pounded the brittle path. Despite the arctic temperature, his bronze body was soaked in sweat. George clung tight to an old rifle, shifting his wild eyes and jerking the barrel between the trees, as if something sinister were hunting him down. In cutoff shorts and long, gray hair, he looked like a castaway gone mad.

It was the last place he wanted to be, the woods, but it was the only way to the beach, and he had to get there quick. The drone of a boat engine spurred him on, making his legs pump faster and focusing his mind on one thought: Keep them away.

The engine grew loud as a chainsaw as George broke through the trees and scrambled down the beach like a savage, brandishing the rifle and charging across the black sand toward a fishing boat headed for the dock. The Acadia was an old vessel, but moved at a good clip. On board were three men, including the captain and steward. The third was Georges lawyer, Nicholas Bonacelli, a small man whose rigid stance and business attire were both distinct and out of place on the sea.

Bonacelli could hardly believe his eyes. He stepped back with a deeply troubled face and whispered, Hes done ithes finally gone mad.

George raised the gun and stopped at the edge of the surf.

What is he doing? the lawyer said from the bridge and waved his hands, Dont shoot.

Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, the captain muttered in something like an Irish brogue.

George aimed the barrel.

The captain cut the motor and the boat drifted silently on the wave. E wont do it.

George fired a shot.

The men hit the deck.

It missed.

Through the crosshairs, George set his bloodshot eyes on the bobbing target. He fired another round that shattered the window of the bridge. The captain staggered to his knees on bits of glass and gunned the engine, turning the vessel in a hasty retreat back to sea.

George nodded and watched the boat for a while, until it was a speck of black on the calm blue sea. The afternoon sky was silvery white and the only sound was the hiss of foamy waves lapping at the beach. George scratched his cheek and the black, threadlike protrusions that covered his face like tiny worms. They had appeared on his forehead months ago, growing larger and spreading, becoming puckered and itchy and a constant source of irritation.

The wind was bitterly cold on the beach and for a while he stood motionless, fighting the feeling of dread. He looked at the sky and shut his eyes, letting the sun warm his face. His mind settled clear and sharp, but it wouldnt be for long. If only hed made the discovery before things had gone so far. Now, it was too late. At least for George.

He turned his head and gazed at the canopy of branches behind him.

Theyve got you surrounded, he whispered and turned back to the sea. No doubt the men would return in the evening or first light of day. There would be police, and a shootout, and then it would all be over.

But it will never be over.

George started back through the woods, barely able to fight them anymore. He could feel their probes creeping back into his brain and he searched the treetops for bits of sunlight. It was the longest mile he ever ran, and somewhere along the way, George dropped the rifle.

The woods ended and he staggered up the path toward his house. He was soon engulfed by smoke from a roaring bonfire. Wooden pallets burned in billowy clouds that stung his eyes as he drew closer to the patio. Plants smoldered and withered in their pouches of dirt and he could hear the seeds popping from the heat.

Coughing and sputtering, he entered the kitchen and collapsed in a chair. His head fell back and his eyes closed, mouth gaping as though he were asleep. Along with smoke and ash, there was a stream of purple dust blowing through an open window, making the lace curtains sway. George could see bits of blue sky through the slits of his eyes. He shut them again and the world stopped moving. He took deep breaths into his lungs and his mind fell freely.

It was a long while before he was aware of time again. The kitchen was aglow with bright orange rays of a sunset over Sparrow Island, and the only sound was George screaming in guttural agony. He lay on the kitchen floor, his body pale as snow and dripping with blood. Knives, forks, scissors, and other sharp things protruded from his arms and legs. The word traitor was carved upside down on his chest. His trembling hand picked up the last instrument of torture, a letter opener, and held the rounded tip inches from his abdomen.

Help me, God, he whispered, with the last bit of voice he had left.

There was only silence. He pressed the blade to his skin and bore down heavily, raising his body off the floor. The point was dull and he had to tighten his muscles to get it to pierce the flesh. There was a loud pop and the metal slid into him with a crunching sound. Blood dribbled like a fountain from the tattered hole. The pain was unbearable. George opened his mouth to scream but released only a gush of air. He laid his head back gently and stared up at the ceiling with a terrifying realization that it would take hours to die; if they let him die at all.

George was broken. His lips silently begged for mercy.

Let go, George.

And he did.

They were back now, in control. George slowly sat up holding a hand against the rush of blood. He staggered to his feet, lifting himself off the sticky red floor and walking a few paces on wobbly legs. He gripped the wall for support and his fingers painted a crimson trail to a photograph taped to the wall: a faded Polaroid of a little girl in a red dress and straggly braids, next to a cardboard blue ribbon with Father of the Year scrawled in a childs handwriting. George was only semiconscious of tugging the photo loose. It was held tightly in his fist.

Outside, the first evening stars poked through a dark blue canvas. Sounds of crashing waves were carried by a northerly wind that drifted over the island. George stumbled across the patio, past a cooling skeleton of ash remains, where flames had devoured layers of the plant specimens hed collected over a year, along with all his personal files and notes.

George headed uphill against the gale, toward the cliffs known as High Peak. Some of the sharp things sticking out of his flesh became loose and fell to the ground, but the letter opener held firm in his gut, its handle whipping back and forth. The photo of the little girl curled inside his grip.