Stephen King

VOLUME IV

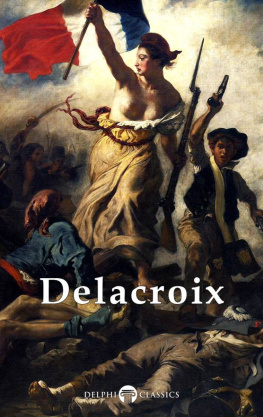

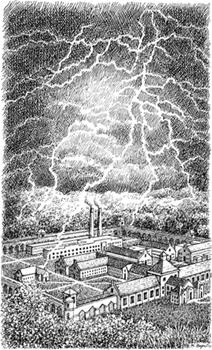

THE BAD DEATH OF EDUARD DELACROIX

ALL THIS OTHER WRITING ASIDE, Ive kept a little diary since I took up residence at Georgia Pinesno big deal, just a couple of paragraphs a day, mostly about the weatherand I looked back through it last evening. I wanted to see just how long it has been since my grandchildren Christopher and Danielle more or less forced me into Georgia Pines. For your own good, Gramps, they said. Of course they did. Isnt that what people mostly say when they have finally figured out how to get rid of a problem that walks and talks?

Its been a little over two years. The eerie thing is that I dont know if it feels like two years, or longer than that, or shorter. My sense of time seems to be melting, like a kids snowman in a January thaw. Its as if time as it always wasEastern Standard Time, Daylight Saving Time, Working-Man Timedoesnt exist anymore. Here there is only Georgia Pines Time, which is Old Man Time, Old Lady Time, and Piss the Bed Time. The rest all gone.

This is a dangerous damned place. You dont realize it at first, at first you think its only a boring place, about as dangerous as a nursery school at nap-time, but its dangerous, all right. Ive seen a lot of people slide into senility since I came here, and sometimes they do more than slidesometimes they go down with the speed of a crash-diving submarine. They come here mostly all rightdim-eyed and welded to the cane, maybe a little loose in the bladder, but otherwise okayand then something happens to them. A month later theyre just sitting in the TV room, staring up at Oprah Winfrey on the TV with dull eyes, a slack jaw, and a forgotten glass of orange juice tilted and dribbling in one hand. A month after that, you have to tell them their kids names when the kids come to visit. And a month after that, its their own damned names you have to refresh them on. Something happens to them, all right: Georgia Pines Time happens to them. Time here is like a weak acid that erases first memory and then the desire to go on living.

You have to fight it. Thats what I tell Elaine Connelly, my special friend. Its gotten better for me since I started writing about what happened to me in 1932, the year John Coffey came on the Green Mile. Some of the memories are awful, but I can feel them sharpening my mind and my awareness the way a knife sharpens a pencil, and that makes the pain worthwhile. Writing and memory alone arent enough, though. I also have a body, wasted and grotesque, though it may now be, and I exercise it as much as I can. It was hard at firstold fogies like me arent much shakes when it comes to exercise just for the sake of exercisebut its easier now that theres a purpose to my walks.

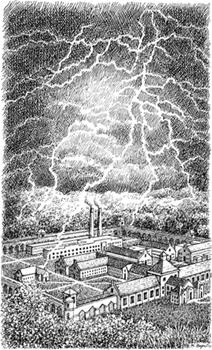

I go out before breakfastas soon as its light, most daysfor my first stroll. It was raining this morning, and the damp makes my joints ache, but I hooked a poncho from the rack by the kitchen door and went out, anyway. When a man has a chore, he has to do it, and if it hurts, too bad. Besides, there are compensations. The chief one is keeping that sense of Real Time, as opposed to Georgia Pines Time. And I like the rain, aches or no aches. Especially in the early morning, when the day is young and seems full of possibilities, even to a washed-up old boy like me.

I went through the kitchen, stopping to beg two slices of toast from one of the sleepy-eyed cooks, and then went out. I crossed the croquet course, then the weedy little putting green. Beyond that is a small stand of woods, with a narrow path winding through it and a couple of sheds, no longer used and mouldering away quietly, along the way. I walked down this path slowly, listening to the sleek and secret patter of the rain in the pines, chewing away at a piece of toast with my few remaining teeth. My legs ached, but it was a low ache, manageable. Mostly I felt pretty well. I drew the moist gray air as deep as I could, taking it in like food.

And when I got to the second of those old sheds, I went in for awhile, and I took care of my business there.

When I walked back up the path twenty minutes later, I could feel a worm of hunger stirring in my belly, and thought I could eat something a little more substantial than toast. A dish of oatmeal, perhaps even a scrambled egg with a sausage on the side. I love sausage, always have, but if I eat more than one these days, Im apt to get the squitters. One would be safe enough, though. Then, with my belly full and with the damp air still perking up my brain (or so I hoped), I would go up to the solarium and write about the execution of Eduard Delacroix. I would do it as fast as I could, so as not to lose my courage.

It was Mr. Jingles I was thinking about as I crossed the croquet course to the kitchen doorhow Percy Wetmore had stamped on him and broken his back, and how Delacroix had screamed when he realized what his enemy had doneand I didnt see Brad Dolan standing there, half-hidden by the Dumpster, until he reached out and grabbed my wrist.

Out for a little stroll, Paulie? he asked.

I jerked back from him, yanking my wrist out of his hand. Some of it was just being startledanyone will jerk when theyre startledbut that wasnt all of it. Id been thinking about Percy Wetmore, remember, and its Percy that Brad always reminds me of. Some of its how Brad always goes around with a paperback stuffed into his pocket (with Percy it was always a mens adventure magazine; with Brad its books of jokes that are only funny if youre stupid and mean-hearted), some of its how he acts like hes King Shit of Turd Mountain, but mostly its that hes sneaky, and he likes to hurt.

Hed just gotten to work, I saw, hadnt even changed into his orderlys whites yet. He was wearing jeans and a cheesy-looking Western-style shirt. In one hand was the remains of a Danish hed hooked out of the kitchen. Hed been standing under the eave, eating it where he wouldnt get wet. And where he could watch for me, Im pretty sure of that now. Im pretty sure of something else, as well: Ill have to watch out for Mr. Brad Dolan. He doesnt like me much. I dont know why, but I never knew why Percy Wetmore didnt like Delacroix, either. And dislike is really too weak a word. Percy hated Dels guts from the very first moment the little Frenchman came onto the Green Mile.

Whats with this poncho you got on, Paulie? he asked, flicking the collar. This isnt yours.

I got it in the hall outside the kitchen, I said. I hate it when he calls me Paulie, and I think he knows it, but I was damned if Id give him the satisfaction of seeing it. Theres a whole row of them. Im not hurting it any, would you say? Rains what its made for, after all.

But it wasnt made for you, Paulie, he said, giving it another little flick. Thats the thing. Those slickersre for the employees, not the residents.

I still dont see what harm it does.

He gave me a thin little smile. Its not about harm, its about the rules. What would life be without rules? Paulie, Paulie, Paulie. He shook his head, as if just looking at me made him feel sorry to be alive. You probably think an old fart like you doesnt have to mind about the rules anymore, but thats just not true. Paulie.

Smiling at me. Disliking me. Maybe even hating me. And why? I dont know. Sometimes there is no why. Thats the scary part.

Well, Im sorry if I broke the rules, I said. It came out sounding whiney, a little shrill, and I hated myself for sounding that way, but Im old, and old people whine easily. Old people scare easily.

Brad nodded. Apology accepted. Now go hang that back up. You got no business out walking in the rain, anyway. Specially not in those woods. What if you were to slip and fall and break your damned hip? Huh? Who do you thinkd have to hoss your elderly freight back up the hill?