Publication of this book has been supported by an award from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Campus Research Board.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: OBrien, David, 1962, author.

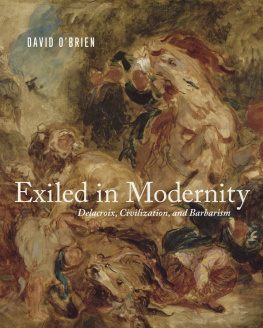

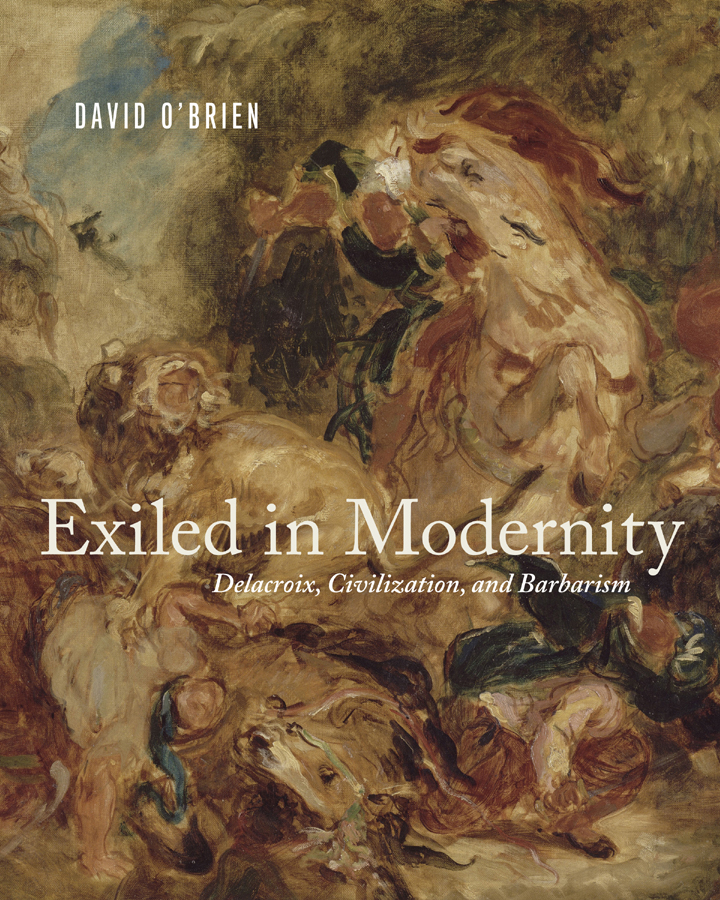

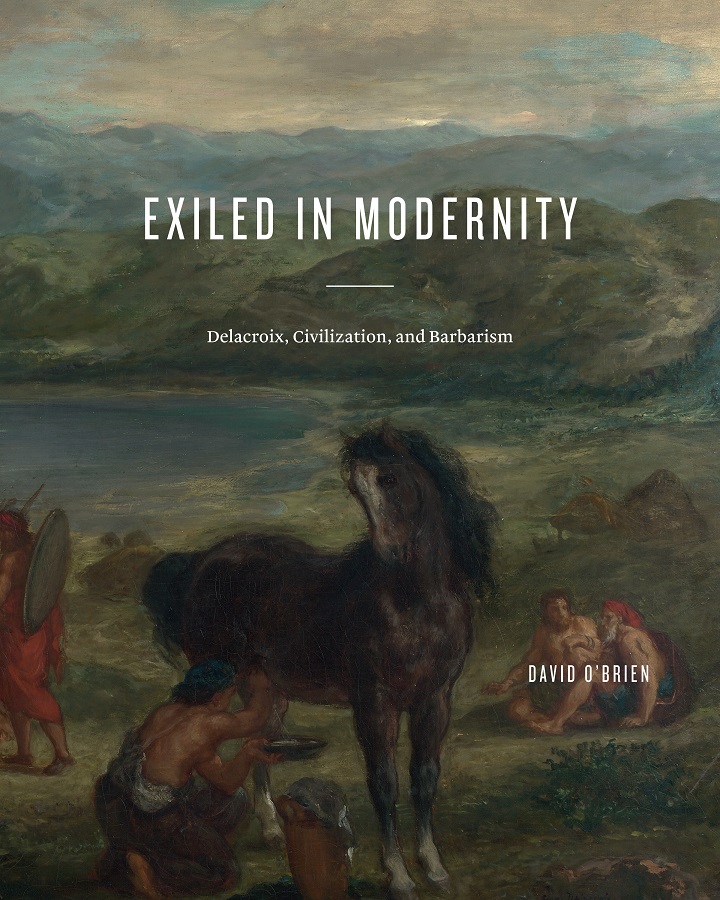

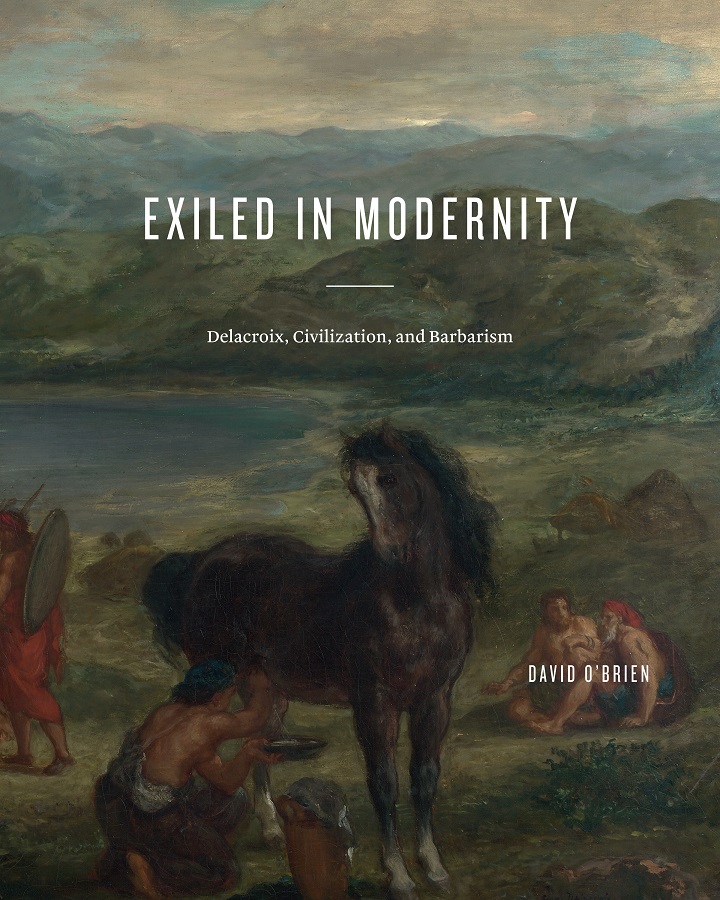

Title: Exiled in modernity : Delacroix, civilization, and barbarism / David OBrien.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Focuses on Eugne Delacroixs fascination with the idea of civilization and the ways this idea informed the artists writing, murals, and paintings of North Africa and animalsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019499 | ISBN 9780271078595 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Delacroix, Eugne, 17981863Criticism and interpretation. | Delacroix, Eugne, 17981863KnowledgeCivilization. | Civilization in art. | Africa, NorthIn art. | Animals in art.

Classification: LCC ND553.D33 O23 2018 | DDC 700/.458dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019499

Copyright 2018 David OBrien

All rights reserved

Printed in China

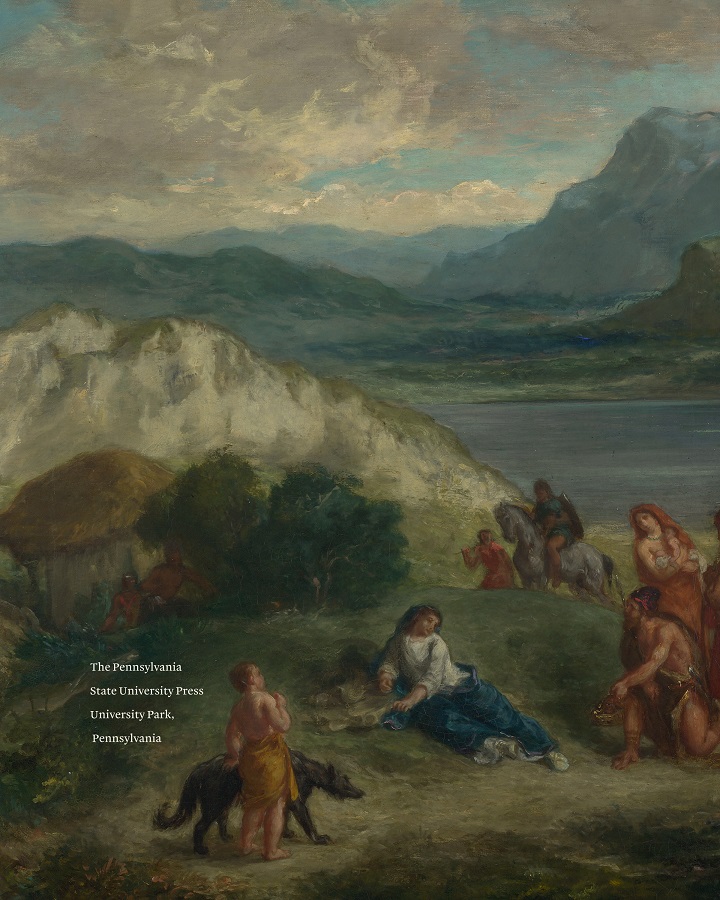

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

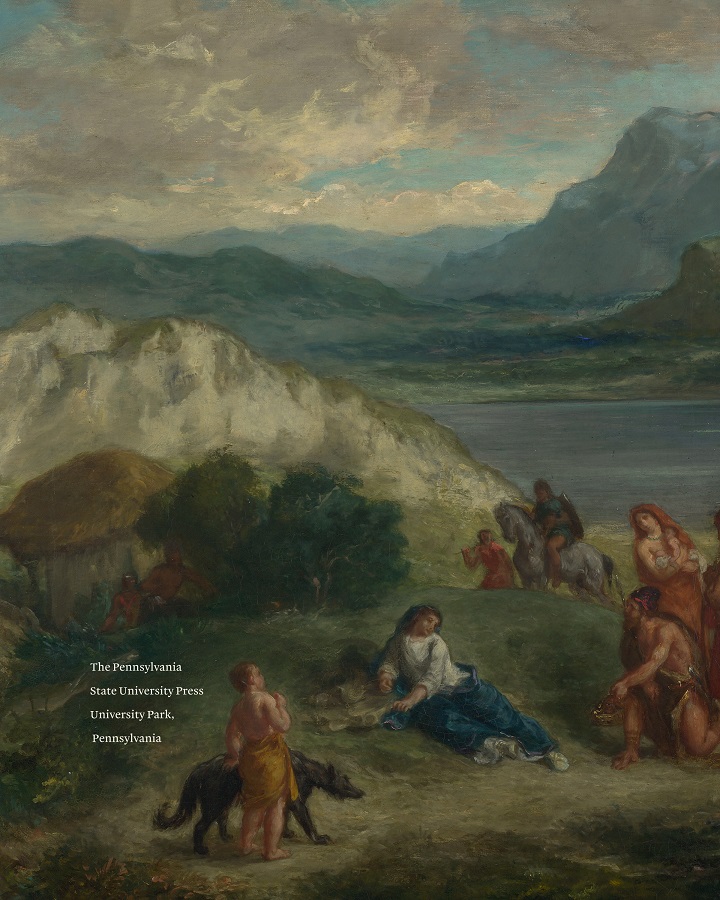

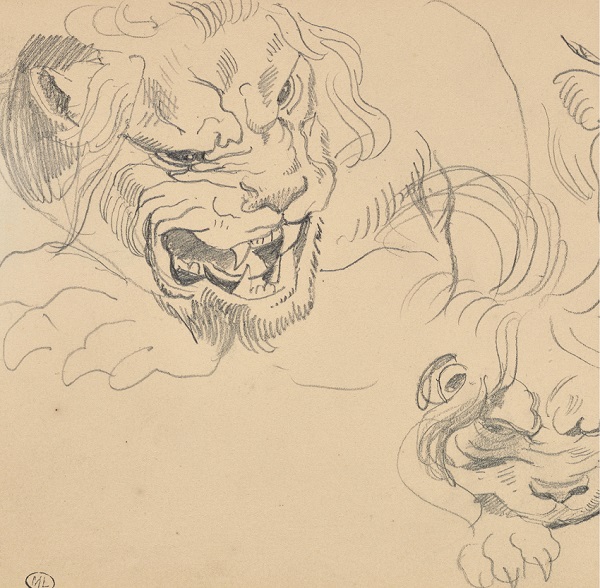

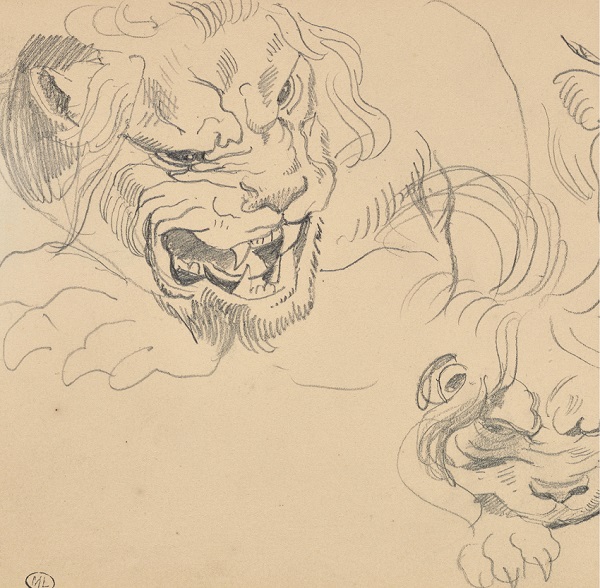

ADDITIONAL CREDITS: title spread, Eugne Delacroix, Ovid Among the Scythians, 1859. National Gallery, London. Bought, 1956. NG6262. Photo National Gallery, London / Art Resource, New York; pages vivii, Eugne Delacroix, Studies After Rubenss Lion Hunt, ca. 1854. Muse du Louvre, Paris. RF 9144, 22 (fol. 13r). Photo RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York (Michel Urtado).

FOR

Maeva & Lucy

CONTENTS

Appendix:

The Paintings in the Library of the Bourbon Palace

When I began this book, more than ten years ago, I could not have imagined the number of people and institutions that would come to my aid. Thank goodness they did. The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the Center for Advanced Study at the University of Illinois, and the Universit de Paris Ouest Nanterre La Dfense all provided critical research support and enabled me to take time away from teaching. At the Muse des beaux-arts in Bordeaux I thank Marc Favreau and Marie-Christine Herv; at the Snat in Paris, Catherine Maynial and Isabelle Girardot; at the Assemble nationale, Eliane Fighiera; at the National Gallery in London, Alan Crookham, Nicolas Donaldson, and Virginia Napoleone.

Many individuals helped me to develop my ideas. In France I wish to thank especially Sbastien Allard, Valrie Bajou, Gilles Braud, Philippe Bordes, Marie-Claude Chaudonneret, Bruno Chenique, Daniella Gallo, Antoine Gournay, Saskia Hanselaar, Berthlmy Jobert, Mehdi Korchane, Rgis Michel, Dominique de Font-Raulx, Franois Pouillon, Philippe Senchal, and Henri Zerner. In the United States I am indebted to Yves-Alain Bois, Elizabeth Childs, Holly Clayson, Lionel Gossman, Daniel Harkett, Katie Hornstein, Dorothy Johnson, Neil McWilliam, Jeanne-Marie Musto, Peter Paret, Mary Sheriff, Daniel Sherman, Susan Siegfried, and Nancy Troy. At the University of Illinois I have been fortunate to count among my colleagues past and present Anne Burkus-Chasson, Jennifer Burns, Jennifer Greenhill, David Hays, Anne D. Hedeman, Chris Higgins, Bob La France, Harry Liebersohn, Areli Marina, Prita Meier, Jordana Mendelson, Heather Hyde Minor, Vernon Minor, Bob Ousterhout, Kristin Romberg, Bruce Rosenstock, Lisa Rosenthal, Dede Ruggles, Dana Rush, John Senseney, Oscar Vazquez, Terri Weissman, Gillen Wood, and the late Larry Schehr.

Many of the subjects at the center of this bookamong others, Delacroix, modernism, primitivism, and art and colonialismwere treated in seminars and courses I taught at the University of Illinois. Numerous graduate and undergraduate students helped me to develop my ideas, including Maria Dorofeeva, Emily Edwards, Dan Fulco, Mollie Henry, Nancy Karrels, Assia Lamzah, and Mary Beth Zundo. I am also grateful to Dan Fulco, Laura Shea, and Maeva OBrien for the work they did as research assistants.

I have the good fortune of counting among my friends two distinguished experts on Delacroix, Margeret MacNamidhe and John Lambertson, both of whom read the manuscript at an early stage and improved it immeasurably with their criticisms and suggestions. Another old friend, Steve Orso, provided critical feedback on one of the very first versions, as did my dear and longtime colleague Marcel Franciscono. Marc Gotlieb, Sgolne Le Men, and Dan Guernsey were early readers of the first two chapters. Their advice changed the book in fundamental ways for the better. , and the conclusion.

Michle Hannoosh came to the manuscript at a late stage and read it again after revisions. I am immensely grateful for the efforts she made to improve it.

At Penn State University Press, I am indebted to Ellie Goodman for her advice at various stages and her unfailing support, to Jennifer Norton for overseeing a very smooth publication process, to Keith Monley for superb copyediting, to Hannah Hebert for helping to organize the permissions and photographs, and to Regina Starace for the beautiful design. Parts of the introduction and was published as Colonial Reproduction: The Contradictions of Nineteenth-Century Orientalist Painting in Contemporary French Civilization 26 (SummerFall 2002). I thank the editors of these publications for permission to reproduce this material here.

One of the joys of finishing this book was the opportunity it provided to put my former dissertation advisors (and now dear friends), Joel Isaacson and Tom Crow, back to work as my readers. Though he retired as an art historian over a decade ago in order to devote himself to painting, Joels sensitivity to Delacroixs art is as strong as ever, and I hope some of it is reflected in these pages. To Tom I am especially grateful for a late incisive intervention that drew out and sharpened my main ideas.

Friends in Paris, including Jake and Dorli Lamar, Sgolne Le Men, Delphine Marchal and Dimitri Mijatovic, Olivier Lhopitallier, Jean-Yves Ollitrault, Pierre and Neije Seignol, Erwann Marchal, Guirec Marchal, and Benjamine Vo Vinh, provided critical moral support. In the United States I found similar encouragement from Christophe and Eve-Laure Moros Ortega, Jim and Jenny Barrett, Phil and Marilyn Best, Csar and Lil Morales, Abby and Craig Bethke, Clare Crowston, Ali Banihashem, Dianne Harris, and Larry Hamlin.

What sustained me most during the years I worked on this book was my family: my parents, my parents-in-law, my brothers and sister and their families, my wife, Masumi, and my two daughters, Maeva and Lucy, to whom this book is dedicated.