This book made available by the Internet Archive.

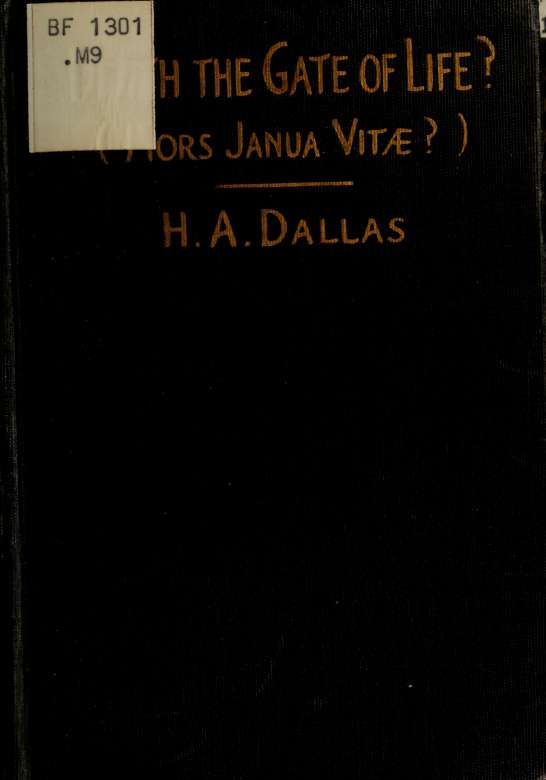

DEATH, THE GATE OF LIFE? ( MORS JANUA VITAE?)

Published 1919 By E. P. Dutton & Company

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States el America.

TO

MY FRIENDS IN BOTH WORLDS

I DEDICATE THIS LITTLE BOOK

IN GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE

AND GLAD ANTICIPATION

a demand on their credulity, and they may, perhaps, formulate in their minds various other conceivable explanations of the facts here presented. It is not likely, however, that they will light upon any hypothesis which has not already been fully considered by the careful experts who have for years been studying these phenomena. I venture to affirm that it is generally those who know comparatively little of the subject who are most ready with the offer of simple explanations, such as fraud, collusion, chance, or mind reading.

Another class of reader will, perhaps, consider that I have claimed too little; that even the small amount of evidence which I have produced would justify wider and fuller deductions than those indicated in this book.

I am aware that I have not only reduced the evidence to a minimum, but that I have also set forth only the most obvious conclusions. This I deliberately aimed at doing. Those who care to assimilate the evidence here summarised, and who are able to accept, at least provisionally, the conclusions based upon it, will have no difficulty in finding further facts for study and in drawing fuller deductions for themselves.

I should like to anticipate one question, which may perhaps be suggested by the perusal of this work : it is this. If those who have died wish to communicate, can they not do so simply and directly? Must there always be an intermediary? Cannot spirit speak with spirit without having recourse to this difficult and strange method? Certainly there are abundant reasons for thinking that telepathic intercourse between minds can be maintained independently of all the channels of sense, and that those who have passed into the Unseen can, and do, directly impress their thoughts upon the minds of their still incarnate friends. But such intercourse does not, as a rule, afford evidence which can be verified in a way to convince those who do not participate in the experience.

Mr. Myers knew r that something more than this was expected from him. He was familiar with the kind of objections raised by sceptics, objections which are by no means unreasonable. He had himself in his lifetime demanded crucial scientific proof of survival, and had undertaken, if such a thing were possible, to afford the necessary evidence in his own case. It would, therefore, have been disappointing if after his death there had

been no sort of attempt to produce proof of a more complex and unequivocal kind than had been previously forthcoming. To produce this was evidently a very difficult task, requiring much effort and ingenuity. It does not follow that all communications between spirits need be of this nature.

I desire to express my sincere thanks to the Council of the Society for Psychical Research for kindly giving me permission to quote at length from the published records of the Society; and I hope that the small work which I am thus enabled to bring out may serve as a useful introduction to the study of those records in their complete form. At the same time, I wish to make it clearly understood that the Society is in no way responsible either for the selection of passages which I quote or for the treatment of the subject. On both these points the whole responsibility rests with myself.

I also wish to acknowledge gratefully the kind assistance rendered by Mr, J. B. Shipley in correcting my MS. and proofs.

IT. A. Dallas.

Hampstead, November 1909.

burns the silly, the credulous and the crazy. The natural human longing to lift a corner of the veil that hides the life beyond the grave, renders a dispassionate consideration of the facts, a calm and critical weighing of the evidence, as difficult as it is imperative. Only by the slow and toilsome pathway of rigorous scientific inquiry can any assured results ever be obtained. We cannot hope in this generation or the next to clear away all the perplexities and pitfalls that confront the investigator in these obscure regions. The methods of science are not the methods of journalism, and though it was to be expected, it is equally to be deplored that the untrained and unscientific have rushed in where many wiser men have feared to tread. Even in ancient times, when, doubtless, there existed a certain esoteric knowledge of some of the psychical phenomena which we have now rediscovered, the approach to this subject was guarded with jealous care. The inquirer needs to be level-headed and to walk warily; whilst the foolish and the fashionable who merely desire a new sensation, the roving journalist and the rapid book-maker, should be warned off so treacherous a ground.

Psychical research, as the author points out, requires to be conducted with care and wise restraint. When this is done we may dismiss as groundless the fear of any injury being done to the psychic. How far any injury may occur to the unseen communicators on the other side is another matter on which we can only form vague impressions. We are led to infer that, on their part, it is a self-denying act of service, for they speak of being "disturbed/*' "suffocated," "kept earth-bound " by trying to communicate, possibly it" involves a partial loss of their personality.

As I have said elsewhere, "indiscriminate condemnation and ignorant credulity are, in truth, the two most dangerous elements with which the public are confronted in connection with Spiritualism. It is because I hold that in the fearless pursuit of truth it is the paramount duty of science to lead the way, and erect such sign-posts as may be needed in the vast territory we dimly see before us, that I so strongly deprecate the past and (to a less extent) the present scornful attitude of the scientific world towards this subject."

The shrinking which some deeply religious minds feel in relation to Spiritualism is, no doubt, partly based upon a mistaken view of

the subject, but it is not wholly irrational. We instinctively feel, as Archbishop Trench has finely expressed it:

" Where thou hast touched, O wondrous death, Where thou hast come between, Lo ! there for ever perisheth The common and the mean."

Whether this be objectively true or not, it is certainly true subjectively to the stricken survivor, and hence the natural recoil from the inane and often vulgar futilities of so many spiritualistic seances. It has, however, long been recognised, and the Society for Psychical Research has clearly demonstrated the fact, that very much of what professes to be communication from an ultra-mundane source is nothing more than automatic expressions of the medium's own mind. And in every case, as might be expected, the communications are more or less influenced by the mental equipment, the personality, of the medium. Hence it is that we find Greek and Latin automatically written by a classical scholar like Mrs. Verrall, and in general a high level of thought expressed in the automatic writings of those cultured ladies, who have in recent years given so much patience and labour to the experimental investigation of this important field of inquiry.