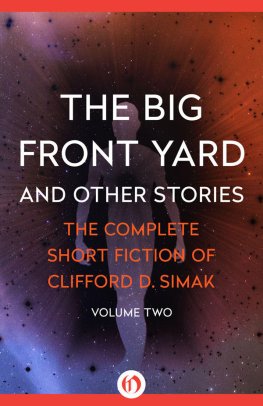

The Thing in the Stone

And Other Stories

The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, Volume Twelve

Introduction

Clifford D. Simak: Seeker After the Truth

by David W. Wixon

His world sounds like a dismal one, she said. Dismal and holy. The two so often go together.

Clifford D. Simak, in Special DeliveranceMost people who have read a fair amount of Clifford D. Simaks fiction will, if asked to give a succinct description of it, resort to mentioning robots, talking dogs, or pastoralism; few will speak of religion.

Probably that is because the term religion, when Simak uses it at all (and he does not actually use the very word all that often), may encompass a wide variety of subjectsfrom theology and philosophy, on the one hand, through ecclesiastical organizations to the most primitive of superstition. Sometimes one of those concepts will be front-and-center in a Simak story (for example Project Pope or The Spacemans Van Gogh, The Fellowship of the Talisman or The Voice in the Void), but often the religious concept is merely a part of the background, almost a sort of throwaway line. However, when viewed in the aggregate, it becomes obvious that all of those lines are there because they came to the mind of the author as he was writing. And the number of those occasions makes it clear in turn that the subject of religion was seldom far from Simaks mind.

Perhaps strangely, this happened even though Simak was never a member of any organized religion or sect. (Occasionally one may find biographical essays about the author which state that he was a Roman Catholic; that is incorrect. Although Simaks Czech ancestors almost certainly were Catholicin fact, one of his prize possessions was an ancient rosary that, he told me, came down through the family from a very devout female ancestorthe family story had it that Cliffs paternal grandfather had cut all ties with the Church following a loud disagreement with a parish priest. And they apparently never picked an alternative.)

But the Simak family had the habit of thoughtfulness, and Cliffs parents, John and Maggie, engaged in a great deal of reading and discussionincluding their two sons from an early age. And it seems clear that if the Simak family had given up the Church, they never gave up most of the principles, the underlying values, which they had learned. (Although it seems a mere detail, I have always been intrigued by the fact that the familys stone, in the old Wisconsin country graveyard in which Cliffs parents lie, is topped by a carved representation of an open book; almost certainly the book, a not-uncommon feature of grave markers of that era, represented a Bible, but I have a suspicion that to the family it had a more generalized meaning, too.)

As I said, Cliff Simak was not a churchgoer. But he was not blind to the concepts we associate with religion (in the most general sense of that word), such as spirituality.

In general, readers and critics seem to conclude that the sense of morality so strong in Simak stories is a traditional one; and while I will agree that Cliff was aware of and influenced by the mores of his time, I would suggest that his sense of morality did not so much result from traditional religion as from the application of the authors common sense to the need of sentient beings to live with each other in the Universe. He used his mind to explore such concepts all through his life, and several times seemed to suggest that there might exist some sort of universal code of ethics that all intelligent beings could subscribe to. (Indeed, even in his last days, when writing was beyond him, one of the works he kept by his chair, to dip into, as he saidwas the collected works of Thoreau I suspect the two men, as writers and thinkers, had a lot in common.)

In light of the frequency with which religious ideas would appear in Clifford D. Simaks stories, it is hardly surprising that the very first of his stories to see print, The World of the Red Sun (1931), revolved around an alien being who came to the Earth of the far future to find the human race fallen into a primitive state and who used his superior powers to set himself up as a god for humankind. And in The Voice in the Void, appearing the very next year, Simak gave an ugly portrayal of the religion of the Martians civilization.

The concept of repulsive primitive religions was, of course, hardly unique to Simak; it fact, it was a frequent feature of adventure fiction in his time. But in 1935, Simak raised a stir among science fiction fans with his story The Creator, which was seen as violating publishing taboos by portraying humans battlingand defeatingthe being who had created our Universe. It would lead to the sardonic labeling of some of Cliffs stories as his sacrilegious stories.

In the following years of his career, Simak used religion, or religious ideas, dozens of times: In Rule 18 (1938), his protagonist, marooned in North Americas past, ends the story resolving to head south to become a god for the Aztecs; and in his first novel, Cosmic Engineers (1939), his time traveling Earthmen have to struggle with an godlike alien who is actually insane. And in one way or another, religion would appear, if only momentarily, in many other of his books and stories, including Project Pope, A Choice of Gods, Time and Again, Time Is the Simplest Thing, Way Station, Mastodonia, Gleanersthe list is long. (And yet, perhaps strangely, there seems to be no trace of such religious notions or influences in the well-known story-cycle known by its collective title, City.)

It should be made clear, however, that Clifford D. Simak, in his mentions of various religious ideas or practices, never really put forward any particular set of religious tenets beyond the suggestion, to which I referred earlier, that there might exist a universally applicable ethical codeindeed, Cliff, in his writing, is best described as agnostic.

But there was an idea that underlay most of Simaks mentions of religion, and it was an idea that went beyond religion, and indeed beyond his science fiction: It was an iconoclasm that also condemned such societal institutions as law enforcement, politicians, banking, and business: the idea that humans have a tendency to cheat their fellows, to use positions of power to tyrannize them.

Cliffs cynical view of religion, then, was not so much about the ideals of religion, of theologyas it was about the way humankind seems to always show a tendency to create religious organizations that are used to gain power or wealth for those running the organizations; he was unsparing in his depictions of churchmen supporting the rights of humans to take the land of nonhumans (Enchanted Pilgrimage); of Bible Belt fanatics (The Werewolf Principle); of religious groups who sought to control time travel so as to be able to prevent others from learning the truth about the founding of Christianity (Mastodonia, Gleaners); of a group of selfish, scheming leeches who fastened on the people by creating a fraudulent religion during a time of societal privation (Enchanted Pilgrimage); of a monastery whose monks were fat, lazy, and spongers off their neighbors (Fellowship of the Talisman); of professional religionists who tried to manipulate a world-threatening crisis (Our Childrens Children); or churchmen inclined to shoot off their mouths in all directions and endlessly and without thought on any given subject (The Visitors).

Do not make the mistake of thinking that Cliff Simak was against all religion; rather, he was concerned to point out how easy it wasand how usualfor people to corrupt religious impulses and ideals. It is notable, for instance, that his most sympathetic portrayal of religious ideas, in The Spacemans Van Gogh, involved a wandering artist who was pursuing a search for his religious idealthat story, that search, had nothing to do with any ecclesiastical organization. (And if I may go out on a limb, I would suggest that The Thing in the Stone seems to hint at an alien version of Christianitys Good Shepherd story.)