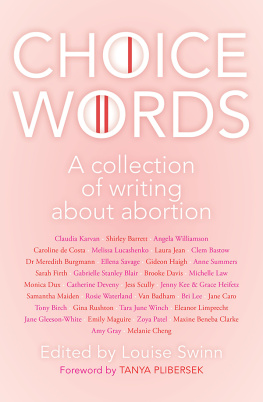

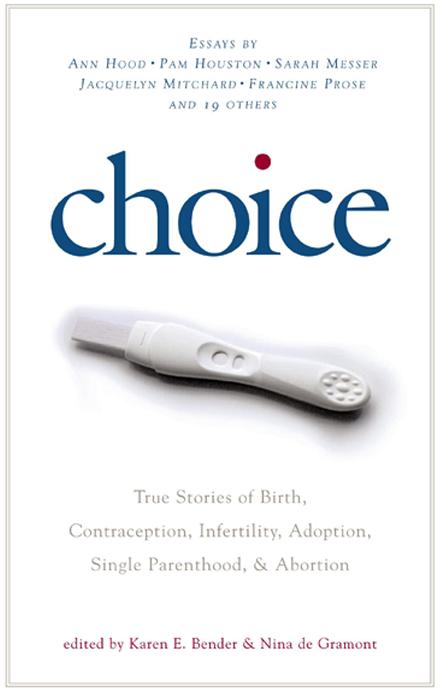

INTRODUCTION

by Karen E. Bender and Nina de Gramont

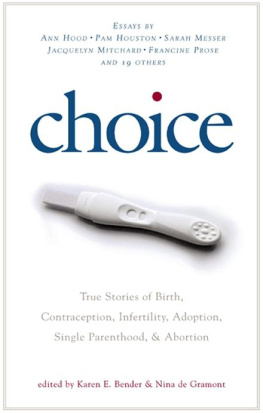

A WOMAN HOLDS a pregnancy test, waiting for a line to appear. In three minutes or less she will have her answer. One pink line. Two pink lines. A blue or pink line. Pregnant. Not Pregnant.

Every day, all over America women stare at this stick and wait.

This woman could be an unmarried teenage girl, crouched in a locked bathroom while her unsuspecting mother makes breakfast downstairs. She could be a childless woman in her late thirties, her husband holding her hand and hoping this time the answer will be different. She could be married to an abusive husband from whom she must hide this test. She could be an exhausted mother of young children, not knowing how she will be able to afford another. She could know that she carries the gene for a frightening disease and be anticipating the answer with hope and dread. She could be the mother of the teenage girl, taking the test herself in a downstairs bathroom, excited about the possibility of starting again on the other side of her reproductive life.

The line appears.

Thirty-four years ago, these women would have had to live with whatever results the pregnancy test delivered. In the near future, some of their choices may be lost. But todayat this precise moment in historythere are many possible paths that they might follow. At this moment in the United States, they have a choice.

This anthology began on the last day of 2005, when we were at a New Years Eve party. The kids had commandeered the living room, tooting noisemakers; we huddled against the wall, trying to hold an adult conversation.

When the conversation turned to politics, we began talking about South Dakotas proposed law to ban all abortions in the state. We couldnt believe such a draconian measure could be instituted in a democracy in our lifetime.

Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s with reproductive freedom a given, the idea that such a basic right could be revoked astonished and disturbed us. Though neither of us had had abortions, wed thought about the issue a great deal and had both explored abortion in our fiction.

Karen said, Ive always thought about compiling an anthology about abortion.

We looked at each other. What would that mean?

We are writers; we have committed ourselves to the power of story as a way of reaching people. First we thought about a book of fictional accounts about abortion. But events in the real world are already dramatic; we wanted a book that would bear witness to the reproductive stories that make up real womens lives.

A few days later at a friends birthday party, someone told us that in South Dakota it was already extremely difficult for a woman to procure an abortion. There is only one clinic in the state that offers the procedure: The Planned Parenthood in Sioux Falls, which performs abortions one day a week. Four doctors from Minnesota fly in on a rotating basis.

How could such a prohibitive law arise from such a minimal practice?

We started talking about what our anthology could include. We told each other experiences of people we knew, traded stories from our own personal histories. As we talked, we realized that every woman we knew had some sort of story involving her reproductive life. What if our anthology focused on true storiesnot only about abortion but about adoption, infertility treatments, the morning-after pill, birth control? Doesnt the word choice refer to all forms of reproductive options?

In this country people can be eager to speak but reluctant to listen. Political division may lead to simplistic, clichd presentation of ideas. As writers and writing teachers, we are sensitive to clichwe urge our students to get to the specific. With specific examples, we tell our students, your ideas will have authority. How could specific stories about choices transcend the clichs of politics?

In South Dakota, Leslee Unruhone of the prime lobbyists for the abortion banhad said, I want abortion to end.

This simplistic statement mirrors the easy proclamations we see and hear every day. We started talking about the bumper stickers we see in Wilmington, North Carolina, where we live:

Against abortion? Dont have one.

Choose life: your mother did.

Keep your laws off my body.

Abortion doesnt make you un-pregnant.

It makes you the mother of a dead child.

These statements are, ultimately, glib. None of these stickers tells us a story about a person who has made a particular decision. None of them really tells us what it is like to make a choice.

Thats what we could call our book, Nina said. Choice.

In 1992 in an interview on NBCs Dateline, the first President Bush admitted that, despite his pro-life beliefs, he would stand behind a daughter or granddaughter who chose to have an abortion. He said, Id love her and help her, lift her up, wipe the tears away, and wed get back in the game. President Bushs statement illustrates the stunning complexity behind this issue. Its one thing to oppose an idea in theory, but once the notion becomes personal and the faces familiar, even a staunch opponent of abortion can imagine not only tolerance, but can imagine supporting a womans personal decision. When nuances are explored and empathy is applied, condemnation gives way to compassion.

In this country, we can be too eager to set compassion aside in favor of judgment. We are not attuned to complexitybut we need to be. As a nation striving to define itself as moral, we need, frankly, to become smarter. How can we rise above having our most potent discussions by bumper stickers, or pundits trading barbs on talk shows? How can we better understand each other as complex, as human?

The answer lies in telling our stories. After all, one of the women taking that pregnancy test could be your daughter. She could be your mother or your best friend. And her story might not end in that bathroom. She could discover that her fetus has a terrible genetic disorder. She could be unable to afford raising a child at this moment in her life, or simply be too young. She might not have a partner. She could learn that carrying the pregnancy to term might put her own life in danger. She might have been coerced into the encounter that led to the pregnancy. She might have been raped.

The word choice encompasses much more than abortion. It includes any of the numerous ways a woman might decide to have or not have a family. As Catherine Newman writes in her essay about conception, Choice in all its many formsadoption, abstinence, technology, choosing to be anti-choice, pleasure, abortion, birth control, kids, no kids, and even, I know, regretis what makes human sexuality truly human and parenthood truly viable.

When an issue is as polarized as abortion, people on both sides see the world in black and white. In order to preserve these extremes, stories that reveal gray areas are kept secret. The woman who regrets placing her child for adoption suffers in silence, lest someone think she would have been better off aborting. The woman who undergoes a painful abortion keeps quiet, lest the complexities of her situation be construed as an argument against reproductive freedom. But when these stories are suppressed, so is our empathy. Instead of listening to each others stories and drawing lessons from each others lives, we are turning a deaf ear to human experience.