Bireme warship, relief from the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina (Praeneste), Lazio Region, Italy (De Agostini/Getty Images)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing

of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

THE ROMAN NAVY or, more accurately, the naval forces of the Roman state, is more often than not consigned to little more than a couple of paragraphs in many accounts of Roman military endeavour. In fact, it was for over 800 years an integral part of the armed forces of that Roman state and became the worlds first super-power navy. It was the instrument by which Rome achieved domination of the western Mediterranean, which enabled her expansion into the lands surrounding it and the foundation of her empire; it was naval forces that enabled the Romans to intervene and eventually to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean and the lands of the near east. It was a naval campaign and a sea battle that established and secured power for the first of the emperors of Rome; it was the navys domination that enabled trade and the economy of the empire to grow and to flourish, free from the scourge of piracy and to an extent not equalled until the twentieth century. Finally, it was the loss of that domination that was a vital factor in the disintegration and ending of the Western Roman Empire. Ciceros dictum that The master of the sea must inevitably be master of the empire (M. Tullius Cicero, 10643 BC, Epistolae ad Atticus 10.8.4, existimat enim qui mare teneat eum necesse [esse] rerum potiri) has proved to be true in every Europe-wide war since. At its height, during the Punic Wars, the navy accounted for fully a third of the total Roman military effort and during imperial times it averaged rather more than a tenth of it.

Surviving evidence relating to the service is sparse and fragmentary but there is overall a body of information about the Roman navy, seafaring and shipping in the ancient world and aspects of Roman life which can be searched to extract a picture of the Roman navy as a whole. In seeking to arrive at a detailed picture of the service, parallel evidence will also have to be relied upon, as will therefore, the argument that it would be unreasonable as well as illogical to suppose that entirely separate arrangements, systems or methods had been employed just for the navy. For example, while on the one hand it seems likely that the armys standard issue sword, the gladius hispaniensis, was also used by the marines of the navy, on the other it seems that the navy adopted a short pike for use in boarding which finds no parallel with the army. Conclusions should not, however, be reached without consideration of the appropriateness of an item. So, for example again, it is well known that the Roman legionary wore sturdy, ventilated boots (caligae) studded with hobnails, but this footwear would have been impractical for a marine, as the hobnails would lack grip on a wooden deck and would quickly rip the surfaces to shreds. One can thus posit that a marines boot, although similar, would have substituted a leather or rope sole; the armys boot is proven, the marines surmised, but well within the technology of the time but there are no surviving examples.

There is some evidence, however, such as inscriptions, wall and pottery paintings, statuary and literary references, that directly relate to the navy. As an example, a votive altar set up by Valerius Valens, in which he describes himself as Praefect[us] Classis Mis[enensis] (CIL X.3336/ILS 3765), prefect of the fleet at Misenum, shows that the post existed in the early third century AD, the date of the altar. There are other traces, too, on the monumental scale; at Carthage, for example, there are the remains of the basins that formed the once great military and mercantile harbours, including the base of an excavated ship shed on the area now known as Admiralty Island. Syracuse has some remains of city walls from ancient times as well as the great Euryalus fortress, the worlds first artillery fort. In Rome the Capitoline Museum houses the plaque erected to celebrate Duilius naval victory at Mylae in 260 BC. At Ostia, by the Marine Gate, the funerary monument of C. Cartilius Poplicola (first century BC) commemorating his military achievements in life is crowned by a representation of a warship of trireme configuration; almost opposite this is a model in marble of a ships ram. There are smaller artefacts, such as bricks bearing stamps of the fleets that had them made, metal diplomas awarded to men upon their retirement from the service and inscriptions and reliefs on monuments and stelae in many museums, as well as wall paintings, such as those from Pompeii.

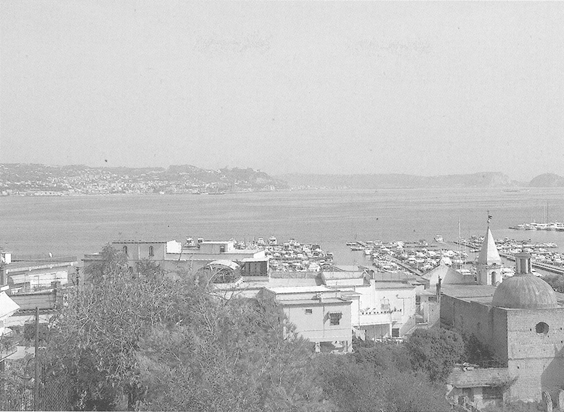

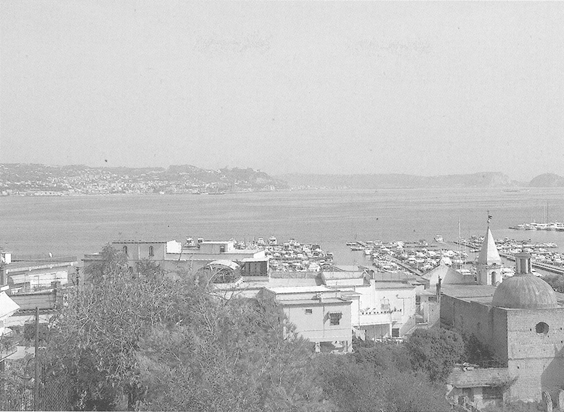

The view from Baia (Baiae) to Pozzuoli (Puteoli). Tiberius philosopher, Thrasyllus taunted Gaius (Caligula) that he could no more become emperor than ride a chariot between them. When he did become emperor, Gaius ordered the nearby Misene fleet to gather every ship that they could find to bridge the distance of some 2 miles (3 km); they built a pontoon bridge from some 2,000 ships, 10 feet (3 m) wide to join them, with islands every thousand paces upon which villages were constructed. Gaius duly rode his chariot across, accompanied by cavalry and infantry, returning across on the following day. (Authors photograph)

Although having had great numbers of ships and men, the Republican navy did not have the great naval bases of later Imperial times and thus little trace remains of it. The Imperial navy did, however, and archaeological excavations have been carried out at many of them, although there is sometimes little to distinguish the remains as distinctly naval as opposed to military. Thus a military hospital unearthed at Xanten (Vetera, Belgium) could serve both the Rhine fleet and local garrisons. One location known to be of naval significance is, of course, Misenum, much of which is now a pleasant, modern holiday town; but there are visible remains of masonry and moles and the base of the temple of the Augustales, the priests of the cult of the emperors, can be seen, the facade of which is in the nearby Bacoli museum. The great cistern can also be visited. At Ravenna, much less remains: a piece of wall and the remains of a mole, now inland. This site is a good example of how in many places changes of shoreline and silting over the centuries mean that the raison dtre and context have been lost. This is not always so, as, for instance, Portchester Castle (Porta Adurnis) in Hampshire, the best-preserved of the shore forts, still stands on the shore at the top of Portsmouth harbour, connected to the nearby Roman road network. The piers, jetties, slipways and quays that once served for the operation of its warship complement have long since disappeared but can be readily envisaged, the context remaining valid.