1. All the American battleships at Surigao Strait were supplied with flashless propellent for their main battery guns. As this image of West Virginia (BB48) firing a half-salvo from her after turrets attests, flashless was a relative term. Flashless powder burned more quickly (and less completely) than the more conventional smokeless powder developed for daylight engagements, meaning that more smoke and less flame emerged from the barrel behind the shell. It is easy to see how the gunfire of Oldendorfs battleships and cruisers produced enough light to silhouette the destroyers of Smoots DesRon56. ( NARA )

C ONTENTS

To my brother, Dick, for setting the bar high before I was old enough to appreciate it and for continuing to raise it higher now that I am .

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A NY WRITER OF HISTORY LIVES SURROUNDED by a support system of friends and colleagues without whose assistance no work such as this could be written. This work is no exception. Many people have helped, in ways small and large, whose contributions I failed to note. To them I offer my sincerest apologies and gratitude. Those whose help I made the effort to record are listed here: Vincent OHara for his unfailing generosity and patience in the face of my many requests for assistance; Enrico Cernuschi for his gracious help with photographs and information on the Mediterranean theatre, particularly the Regia Marina; Randy Stone for his willingness to share his encyclopedic knowledge of US Navy actions in the Pacific and to fact-check my write-ups at several points; Rick E. Davis, who helped with photo identification and generally useful information; and Dave McComb, who ran the Destroyer History Foundation and its indispensable website www.destroyerhistory.org. Sadly, Dave passed away in July 2014 at far too young an age. His contribution to the community of naval historians will be sorely missed, as will his unfailing willingness to share his knowledge. More anonymously, but no less importantly, I wish to thank the staffs at the US National Archives, College Park, MD and The National Archives, at Kew, Surrey in England.

The help of all these fine people was invaluable, but, as always, any mistakes of omission or commission are mine alone.

Photo Credits

Most of the photographs come from the US National Archives, which contains the US Navys photographic assets for the time period covered by this book. Others have been sent to me by friends and colleagues over the years and, if I was wise enough to record the source, are credited as such. If I happened to note the original source, that is credited as well. One source in particular needs special mention. Enrico Cernuschi generously made available to me a collection of photographs of Italian ships engaged in the Battle of Punta Stilo, which was given to him by Admiral Giovanni Vignati, editor of Marinai dItalia magazine. The full credit for these images is Associazione Nazionale Marinai dItalia. Fondo ANMI, collezione Castegnaro, which I have shortened in the captions to ANMI via Cernuschi. I also wish to thank Toni Munday of the HMAS Cerberus Museum. Other photo sources are abbreviated as follows:

| NARA | US National Archives and Records Administration |

| NHHC | US Naval History and Heritage Command |

| NRL | US Naval Research Laboratory |

| NZOH | New Zealand Official History |

| USAF | US Air Force |

I would also like to thank Ken MacPherson, Bob Cressman and David Doyle, who have made photographs from their collections available to me over the years.

I NTRODUCTION

T HE PREMISE OF THIS BOOK IS quite simple to recount some of the most interesting and important naval gun battles of the Second World War. Possibly the most difficult part came at the very beginning, deciding which of the many naval engagements to describe, which to exclude and how much background was necessary to place them in context. As this author has always had a strong interest in the technology of naval warfare, one criterion was that, taken in sequence, the chosen engagements should trace the evolution of naval gunfighting from the beginning to the end of the war, showing how changes in technology helped (or hindered) the process of destroying enemy warships by gunfire. The authors intent has also been to include those engagements that are of the greatest interest because of their influence on the course of the war or because they involved the most intriguing ships and men.

To be considered for inclusion in this study, a battle must have been primarily decided by naval gunfire. This deliberately excludes not only the famous carrier air battles such as the Coral Sea and Midway, but also some very interesting engagements in the Solomons Campaign that were primarily exchanges of torpedoes. It also excludes engagements which, while not considered carrier air battles, were nonetheless primarily decided by air attack, such as the dramatic Battle off Samar. Finally, the author has chosen to exclude actions already described in detail in others of his books, such as the battles of Narvik or the naval battle of Casablanca.

This still leaves a large number of engagements from which to choose. Therefore, in making the final selection, the author opted when possible to favour lesser-known engagements over more famous ones, to include engagements from all periods of the war and as many theatres and nationalities as possible and to include engagements involving both large and small warships. Ultimately, it is the authors hope that the result is a book that meets all these criteria, that is a coherent and interesting depiction of the ebb and flow of the Second World War at sea and at the same time pays proper tribute to the ships that carried the guns and to the men who manned them.

The single greatest driver of change in the practice of naval gunnery during the Second World War was the rapid development of more-capable sensor systems. In order to understand how the advent of vastly improved sensors, primarily radar, and the genesis of the necessary shipboard command facilities, it is necessary to look briefly backwards at the revolution in warship design that took place in the century preceding these events. By the end of the 1850s, most warships being built for major navies were steam-powered and the first armoured ships were entering service. Admiral Nelson would have known how to fight these ships because, despite their steam propulsion and armoured sides, their guns were muzzle-loaders and were carried in individual mounts along the broadside, so the tactics of Trafalgar would have sufficed fifty years later. Fire control would also have looked the same, with ships officers telling the guns when to start and stop firing and, in only the most general terms, where to aim. Everything else was left up to individual gunners.

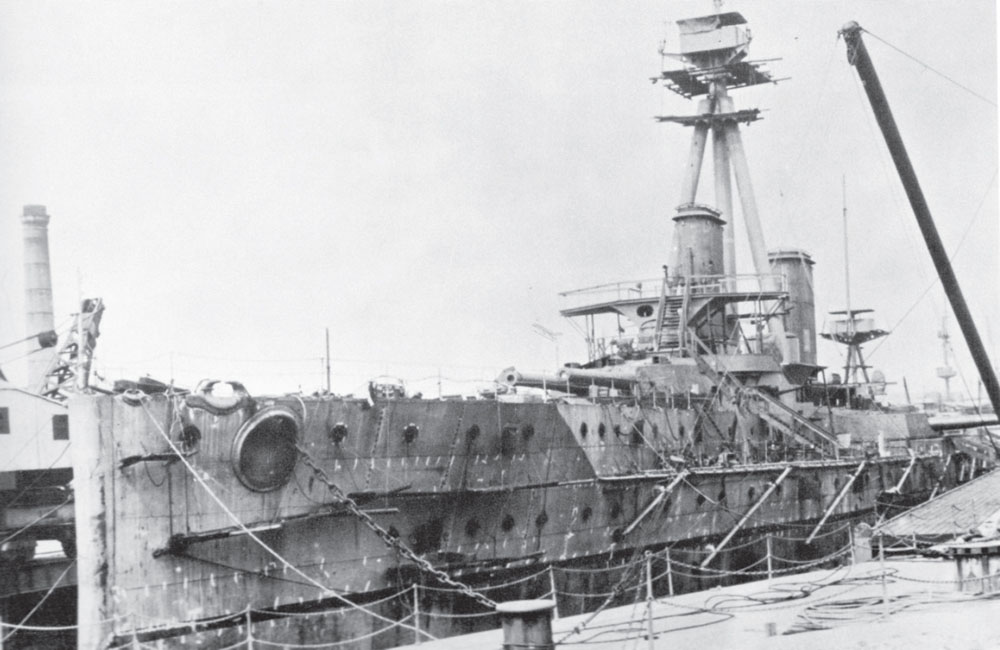

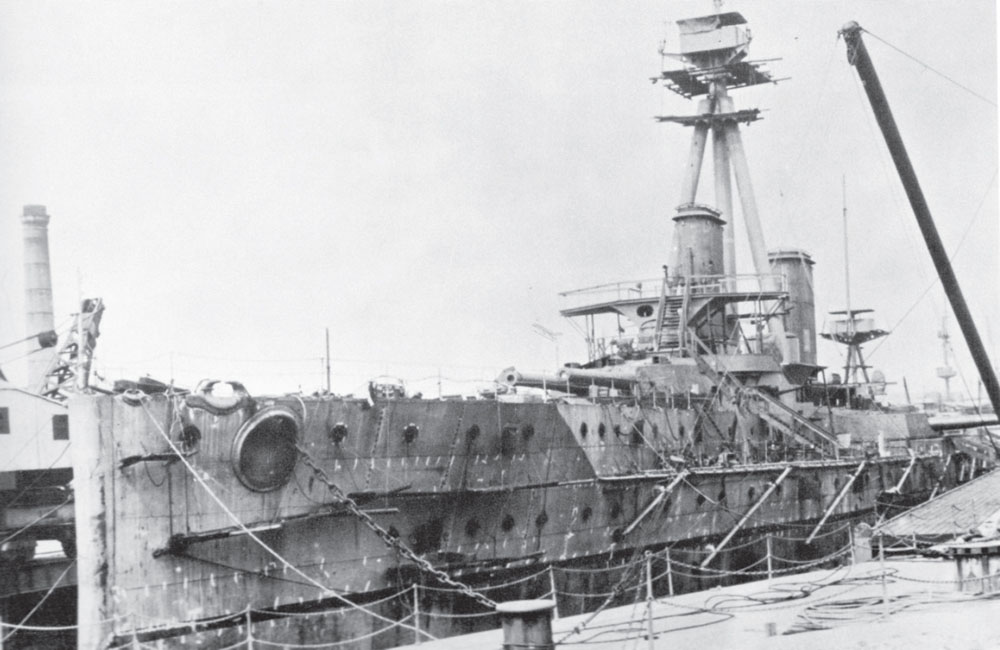

2. When the first of the all-big-gun battleships HMS Dreadnought was under construction in 1905, all that was thought necessary for fire control was a spotting top aloft on a tripod foremast, never mind that it was placed abaft her fore funnel, where it would often be shrouded in smoke. With four main battery turrets on each broadside, the need for more than spotting from the foretop became obvious to Royal Navys gunnery experts, such as Captain John Jellicoe. ( NHHC )