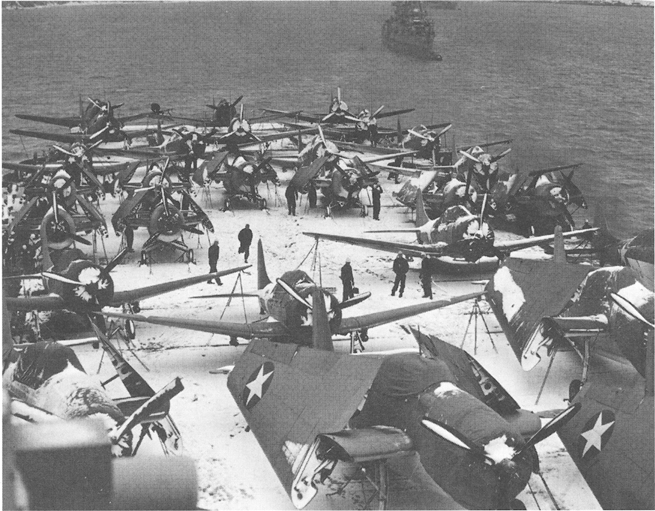

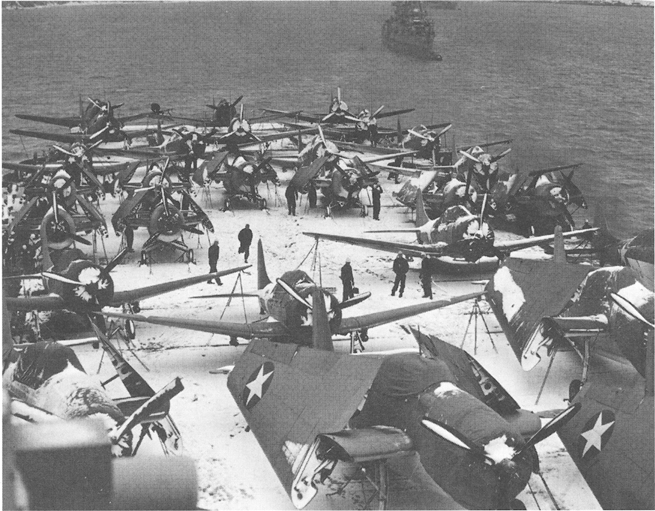

Among the joys of operating in the North Atlantic was the occasional layer of snow on the flight deck and aircraft, as seen on Ranger (CV4) at Argentia, April 1943. Four Avengers can be seen nearest the camera, then four Dauntlesses, eight Wildcats and then eleven more Dauntlesses. (NARA)

The US Navy

and the War in Europe

Robert C. Stern

This is dedicated to my lovely, ever-patient wife, Beth, who, once again, put up with my obsessive concentration on events that took place 60-odd years ago, before either of us was born.

Copyright Robert C. Stern, 2012

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Seaforth Publishing

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley

S Yorkshire S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Email info@seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP data record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-84832-082-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

The right of Robert C. Stern to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Typeset and designed by Palindrome

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group

Contents

A Queer Idea of Neutrality

September 1939November 1940 |

Just Short of War

November 1940December 1941 |

The Learning Curve

December 1941September 1942 |

Friends & Enemies:

The Landings in North Africa

October 1942November 1942 |

Climax in the Atlantic

November 1942October 1943 |

Into the Middle Sea

November 1942May 1944 |

Assaulting Fortress Europe

August 1942April 1945 |

Finishing the Job in the Atlantic

November 1943May 1945 |

A book like this cannot be written without assistance from a great many people. This work is no exception. Many people have helped in ways small and large whose contributions I failed to note. To them I offer my sincerest apologies and gratitude. Those whose help I made the effort to record are listed here:

Captain Jerry Mason, USN (Ret), who created and maintains the U-boat Archive website, both for that site, which is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in the Second World War in the Atlantic, and for his generosity in answering my questions,

Vincent OHara, and through him, his friend Enrico Cernuschi, for their help clearing up what happened on dark nights in August 1944 off the southern coast of France and for an advance copy of his article on the Naval Battle of Casablanca,

Richard Worth, for reading over some parts of this book and for supplying much vital information, especially the Mordal account of the Naval Battle of Casablanca,

Dave McComb, who runs the Destroyer History Foundation and its indispensable website, www.destroyerhistory.org,

Rick E. Davis, who helped with photo identification and generally useful information,

Kevin McKernon, for sharing his resources and his firm conviction that Corry (DD463) was sunk by German gunfire on 6 June 1944 and not by mining,

Michael Mohl, for permission to use photographs found at the NavSource Naval History site (www.navsource.org), most of which are USN photographs, but some are from private sources, and

More anonymously, but no less importantly, I wish to thank the staffs at the US National Archives, College Park, MD, and the British National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey.

The help of all these fine people was invaluable, but, as always, any mistakes of omission or commission are mine alone.

Almost all the photographs used in this book were copied by the author from the several imagery sources at the US National Archives. Most are from the US Navys Second World War photography collections: Record Group (RG) 80, the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) collection, and RG 19, the Bureau of Ships (BuShips) collection. Some were appended to action reports found in the Modern Military Records section, also at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) facility in College Park, MD.

The other primary source is the Naval History & Heritage Command (NHHC formerly the Naval Historical Center), the US Navys repository of all Second World War photography not at NARA.

The few photos that are not from NARA or NHHC are credited as appropriate. If a photo has no credit, it simply means I failed to record or have lost the record of the source of the photo. I apologize to any who are thus unacknowledged by my sometimes poor record-keeping.

When 1918 had drawn to a close, the world may have finally seemed well ordered from the perspective of the victorious Allies, but there were already dangerous currents at work that would see Europe engulfed in war again in barely 20 years. Unfortunately for the European Allies, the forces available to meet the threat of a resurgent and rearmed Germany, backed by Fascist Italy, were in no way comparable to those they had wielded in 1914, much less 1918. Russia was no longer an ally; indeed, it signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany a week before the new war began. France was still suffering physically and psychologically from the bloodletting required to win in 1918. Great Britain no longer possessed the dominant navy it had in 1918 and its army or air forces, even when combined with the French, could not match the size or equipment of the German Wehrmacht.

By the summer of 1918, with the crucial addition of Americas fresh armies, the Allies finally had the strength to win the land war in France. The US contribution to winning the naval war against Germany was far less decisive. The unrestricted U-boat campaign that began in February 1917 took a terrible toll of the shipping on which Great Britain depended, but the Royal Navy was able to prevail in 1918 with little help from the Americans. When war broke out again in 1939, the Royal Navy was far less prepared to meet the challenge, in particular lacking the escort ships needed to defeat a U-boat campaign that was for all intents unrestricted from the first day of the war. There would be no immediate help from the Americans, who appeared content to let the Europeans sort out their petty squabbles.

War, by its very nature, spawns mythology, whether in victory or defeat. These myths come in many forms, all the way from the stab in the back story believed by right-wing groups in Germany after the First World War to the firm belief by US Isolationists of the 1920s and 1930s that US involvement in that war had been a costly and unnecessary mistake. Polling numbers revealed the strength of this belief among Americans. (In 1937, when Europe appeared poised on the Most Americans consistently described themselves as being opposed to involvement in a war in Europe, but at the same time a solid majority felt that the US should be aiding Great Britain in every way short of war, even if that meant putting US sailors in harms way.)