For My Parents, Who Believed

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

1975 by the United States Naval Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Naval Institute Press paperback edition published in 2016.

ISBN: 978-1-68247-183-8 (eBook)

Library of Congress Catalogue Card No. 74-31739

Unless otherwise indicated by a credit line, all photographs are official U.S. Navy.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

An ill-favoured thing, sir, but mine own.

Shakespeare, As You Like It

Before you judge this or that officer harshly... imagine yourself on the bridge of a little ship, in pitch black night, with the wind howling and spray drenching you continually, and in close proximity to a hundred other ships that you can feel but not see. Then imagine an emergency of some sorta collision, a submarine attack, an engine breakdownand decide whether you could make a quick and correct decision!

John W. Schmidt, U. S. Navy

Oh, theyve got no time for glory in the Infantry ....

Frank Loesser, The Ballad of Rodger Young

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

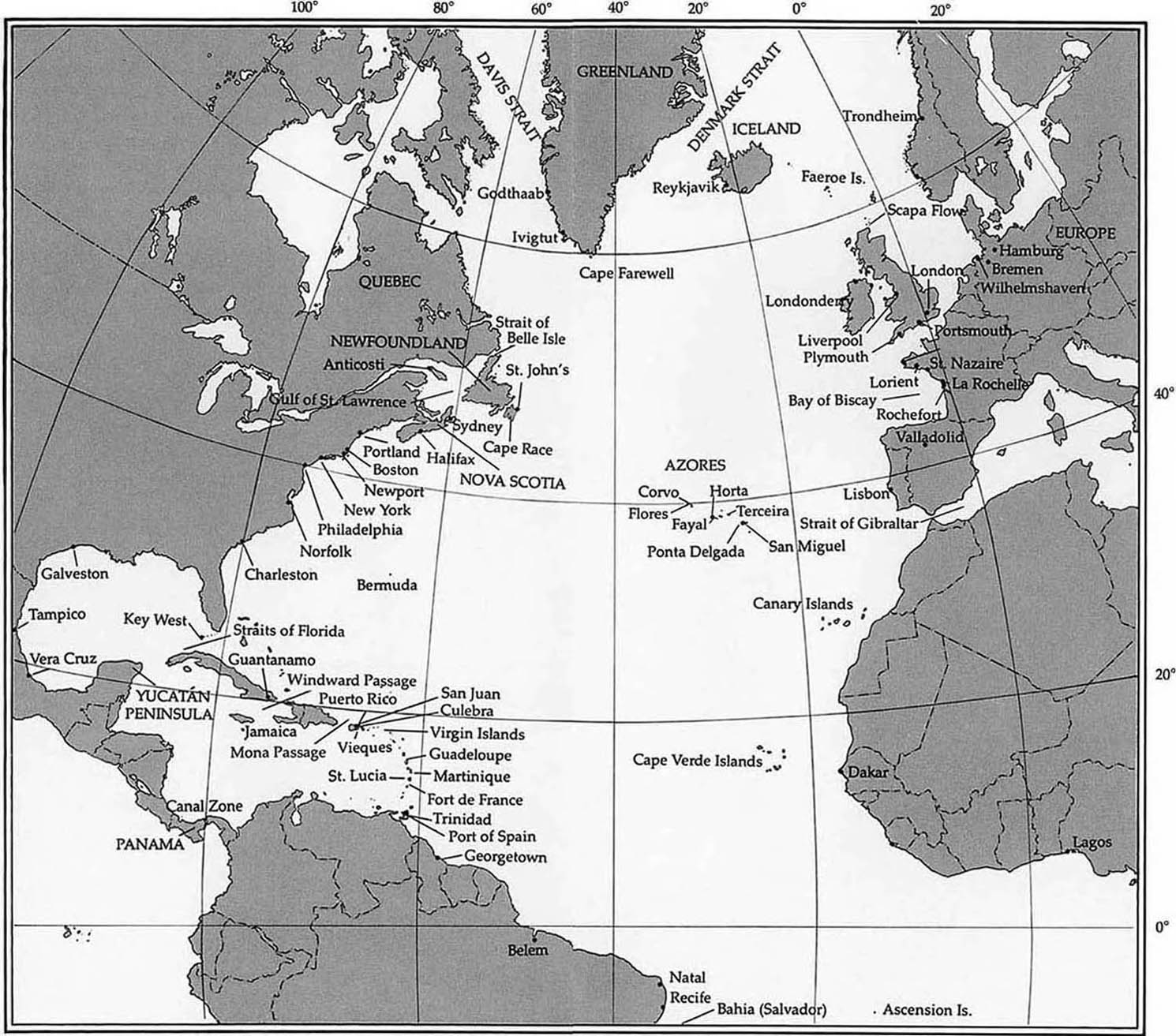

CURIOSITY IS THE BEST PROD OF RESEARCH, and this book has its origins in curiosity. As student and historian, I have long had an interest in strategic studies and the study of battle; and when reading the history of World War II, I sometimes came upon brief, cryptic, tantalizing references to American combat operations at sea months before the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. For the U.S. Navy was at war in the Atlantic long before 7 December 1941: the first American warship to sustain damage and loss of life in battle in World War II was the destroyer USS Kearny, torpedoed in the North Atlantic more than seven weeks before Pearl Harbor; the first American warship sunk in combat in World War II was the destroyer USS Reuben James, torpedoed in the North Atlantic more than five weeks before Pearl Harbor. Surely such combat reflected wider operations, and suggested an undeclared naval war in the Atlantic. What were those operations? What exactly was the U.S. Navys role in the Battle of the Atlantic prior to American entry into the war? To what extent was the Navy escorting Allied convoys? Were there many contacts and battles with German U-boats? Were there many casualties? Were there morale problems, as there often are in limited, undeclared wars? What were the problems, hardships, and lessons of early naval operations in the Atlantic? Numerous tactical questions suggested themselves. And the tactical questions suggested strategic questions. To what extent was the classic American strategy of sea power still valid in the age of the airplane and submarine? What was the U.S. Navys state of readiness to conduct modern operations of sea warfare at the outset of World War II? How did Franklin Roosevelt manage and control his Navys limited, undeclared war? The numbers of my questions increased, but I found scant answers in published sources; most historians of naval operations were primarily concerned with post-1941 events and the great battles of the Pacific War.

Then necessity prodded curiosity. Wanting a topic for scholarly research, I was determined to work in some area of the operational history of World War II; much of that area having been amply written about (although not always adequately researched), I sought a virgin corner of the field. The merger of curiosity and necessity produced a decision to write a study of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet and its role in the undeclared war and after.

The result of my research is this book. It is the story of a fleet, the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, its education at war, and its impact upon strategy.

And perhaps the best reason why the story of the Atlantic Fleet needs to be told can be summed up in a personal anecdote. Recently, I was sitting in my college office, passing time in a pleasant discussion of historical topics with several colleagues. The subject turned to the high quality of American military and naval leadership at the time of World War II, and I contributed a few sea stories about the redoubtable Admiral Ernest J. King; then while making a point about pre-war planning, I happened to mention the sinking of the Reuben James with heavy loss of life on Halloween morning, 1941. Surprised, one of my colleagues, a capable professor who has taught American history at the college level for seven years, interrupted, saying, Wait a minute. That was before Pearl Harbor! What was the Navy doing at war in the Atlantic at that time?

I told him to read this book.

IT WAS ONLY EIGHT DAYS before Christmas, 1937, but none of the men seated at the long table in the Cabinet Room took note of the season. Five days earlier, Japanese aircraft had bombed and sunk the U.S. gunboat Panay in the shallows of the Yangtze River. And now, the Secretary of the Navy, Claude A. Swanson, was telling his colleagues and President Franklin Roosevelt what should be done about this latest crisis in the Far East. Swanson was a stiff, gaunt man; seriously ill, he could not stand up unsupported. White-haired and sallow, he spoke earnestly, a long, full, gray moustache rising and falling with the movement of his lips. He spoke in a thick, gravelly voice which made it difficult for his listeners to understand what he was saying. Sometimes his words gargled together, and only harsh rasps, scratchy and phlegmy, could be heard above the small, restless noises that men make when they are listening to another speak. Secretary Swanson spoke of the need for force; at the least, the U.S. Fleet should be moved from the West Coast to Hawaii.

In a dreamy, distracted way, the crotchety Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes, evaluated the proposals of his infirm colleague. He sensed in Swansons urgency something of the shiny-eyed tenacity of the half-dead man who wants to precipitate grand events to mark his passing. Ickes had absorbed much of the strident, ingenuous pacifism of the liberalism of his generation; indeed, he had once deemed it virtually immoral for the President to allocate WPA funds to the construction of warships. Yet, increasingly, he was coming to believe that he who turns the other cheek gets slapped with the other hand; he feared that only force might restrain the totalitarian regimes. So, almost despite himself, Ickes wondered if the Secretary of the Navy might not be right. If we had to fight, he told himself, perhaps it was a case of better now than later.

Henry Morgenthau, the balding, sad-eyed Secretary of the Treasury, knew that the old man was saying things that needed to be said. Morgenthau had moved through this dismal week with an ache of rage and shame stabbing at him with the remorseless insistence of an abscessed tooth. Outraged by the Japanese attack, he was appalled and then ashamed at the number of people in the government who preferred to ignore the fate of the