All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press.

Gillis, Alex A killing art : the untold history of tae kwon do / Alex Gillis.

1. Tae kwon doHistory. 2. Choi, Hong Hi. 3. Kim, Un-yong, 1931-. 4. Gillis, Alex. 5. Tae kwon doBiography. I. Title.

This book is set in Sabon and Choc, and is printed on paper that is made of 100% post consumer waste content.

Introduction

The farther away you are from the truth, the more the hateful and pleasurable states will arise. There is also self-deception.

Bodhidharma, as quoted in The Bodhisattva Warriors

Tae Kwon Do leads to enlightenment along one of five paths, some people believe, but I have my doubts. I am stuck on the path of Courtesy, which instructors in small gyms around the world know well but which is largely ignored by Tae Kwon Do's leaders. This book is about Courtesy, Integrity, Perseverance, Self-Control, and Indomitable Spirit the tenets of Tae Kwon Do a true story about a martial art that I love in spite of its bizarre and wondrous history. Most of us have heard about Tae Kwon Do through children, whose laughter dominates evening and weekend classes in North America, but the art hides a history of secret-service agents, gangsterism, and fearsome weaponry, as one of its founders, Choi Hong-Hi, once described it. He wrote that Tae Kwon Do is able to take lives easily, when needed, by defending and attacking 72 vital spots using 16 well-trained parts of the body. Choi had a fondness for numbers. He liked their devastating precision.

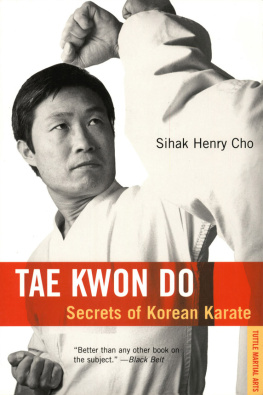

Few young people in Olympic Tae Kwon Do know about Choi, who more than anyone deserves the label founder in this martial art. Other founders and there are many erased him from the popular record long ago. A Killing Art restores him and his pioneers to their place in Tae Kwon Do history. This book is based on Choi's memoirs, the memoirs of Kim Un-yong (a founder of Olympic Tae Kwon Do), and on the hundreds of interviews and documents that I list in the footnotes and bibliography.

I would like to thank many people, especially Choi Hong-Hi, Jung-Hwa Choi, and a handful of martial arts masters and grandmasters, such as Joe Cariati, Joon-Pyo Choi, and Jhoon Rhee, for sharing their astonishing stories. Rhee, in particular, set me straight on much of Kim Un-yong's and Tae Kwon Do's history in the 1960s and 1970s a story of sports mixed with politics, espionage, and myth. Jung-Hwa Choi was open about the art's history from the 1980s to the present, and I want to thank him for his frankness. Sun-Ha Lim told me about the lives of Koreans during the Second World War and the Korean War. The work of historian Bruce Cumings provided a context for Tae Kwon Do's role within modern Korea, both North and South.

Some grandmasters bravely recounted what others were reluctant to share: Nam Tae-hi, C. K. Choi, Kong Young-il, and Jong-Soo Park (my former instructor), for instance. Some interviews were off the record and I thank those men, too. My other instructors, the WTF's Yoon Yeo-bong and the ITF's Park Jung-Taek, Phap Lu, Alfonso Gabbidon, and especially Lenny Di Vecchia, inspired me in the martial art and in my research and interviews.

Mr. Di Vecchia, in particular, inspired me to write the book; he peppered his intense martial arts instruction with history, moral training, and a sense of humour that prevented his students from taking themselves too seriously even though the training itself was deadly serious. I liked his after-class aphorisms. One of them was two words long: Keep moving. He said that a doctor had told him that once and that it referred to more than your body and thoughts.

I would never have finished this book without my black belt friends Floyd Belle, Martin Crawford, Marc Thriault, and many others who meet every Saturday to practise Tae Kwon Do without politics or talk, an increasingly rare situation in the world of black belts. A journalist once telephoned a famous grandmaster, Duk-Sung Son, for an interview, but Son said, No, no more talking. I'm going to train now, and he hung up. My training with Mr. Di Vecchia, Floyd, Martin, and Marc countered the darker parts of this book. Many times, I'd finish a difficult interview or chapter and trudge to the gym, hoping to find them there for more training and less talk hoping for a reprieve.

For editing, research, and support, thank you to Loren Lind, Mark Dixie, Susan Folkins, Jane Ngan, Katie Gare, Diane Gillis, Rene Sapp, Laurie Gillis, and Hana Kim, who is the Korea Studies Librarian at the East Asian Library at the University of Toronto. John Koh was an excellent translator and interpreter who offered insights along the way. Thank you also to the Ontario Arts Council for grants, and to Michael Holmes and Jack David at ECW Press and to my agent, Hilary McMahon, who warmly encouraged me even on her days off.

And a special thanks to Deborah Adelman, who made more sacrifices for this book than perhaps she should have.

About Korean names

Tae Kwon Do is usually spelled Taekwondo for the Olympic sport (run by the World Taekwondo Federation) but Taekwon-Do for the traditional style (the International Taekwon-Do Federation). Instructors from both styles sometimes use Tae Kwon Do, and there has been so much overlap between the WTF, ITF, and their offshoots that I have stuck with Tae Kwon Do throughout the book, except in titles and quotations from documents.

Most Koreans have three names and write their family names first, but some switch the order. So Kim Un-yong, for example, can be written Un-yong Kim. A hyphen connects the first names, with the second word of the first name beginning with a lower case letter (Un-yong), but many Koreans begin both with an upper case letter, with or without a hyphen (Un Yong and Un-Yong). The whole thing can be confusing. I settled on using either what the person in question uses or on the Korean standard, which is last name first (Kim Un-yong).