Mauve is the story of a man who invented a colour, and in the process transformed the world around him.

Before 1856, the colour in our lives derived from animals, minerals or plants. Clothing, paint, print their reds and blues and blacks came from insects or molluscs, roots or leaves, and dyeing was painstaking and expensive. One royal procession required ten million dead insects. But in 1856 a chemist called William Perkin discovered a way to produce colour in a factory.

Perkin found mauve by chance, at the age of 18, working on a treatment for malaria in his tiny home laboratory in London. Instead of artificial quinine he made a dark oily sludge, but it was a sludge that turned silk a beautiful light purple. The colour was unique; it became the most desirable shade in the fashion houses of Paris and London.

Mauve led to new crimsons, violets, blues and greens, and earned its inventor a fortune, but its importance extended far beyond ballgowns. Before mauve, chemistry was largely a theoretical science. After it, science created huge industries, and the impact of the new colour had fundamental effects on the development of explosives, perfume, photography and modern medicine.

Perkin is honoured with the odd plaque and bust in colleges and chemistry clubs, but is otherwise a forgotten man. This is his story, and the story of how the reputation of a pioneering genius endures. Above all it is a fascinating tale of how the birth of a colour set in motion an extraordinary scientific leap forward that would change the world forever.

For BJ, Jake and Diane

CONTENTS

PLATE 1: William Perkin in 1852

August Wilhelm von Hofmann (181892), engraving by C. Cook (Sheila Terry/Science Photo Library)

William Henry Perkin in 1870 (Science Museum)

PLATE 2: Print from recipe book of Roberts, Dale and Co., Cornbrook Chemical Works, 1862 (Jean Horsfall/Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester)

Selection of early nineteeth-century synthetic dyes and dyed material , including Perkins original bottle of mauveine dye (Science Museum)

PLATE 5: Perkin and his laboratory assistants, 1870 (Science Museum)

Greenford Works in 1858 and 1873

PLATE 7: The Perkin Medal (Science museum)

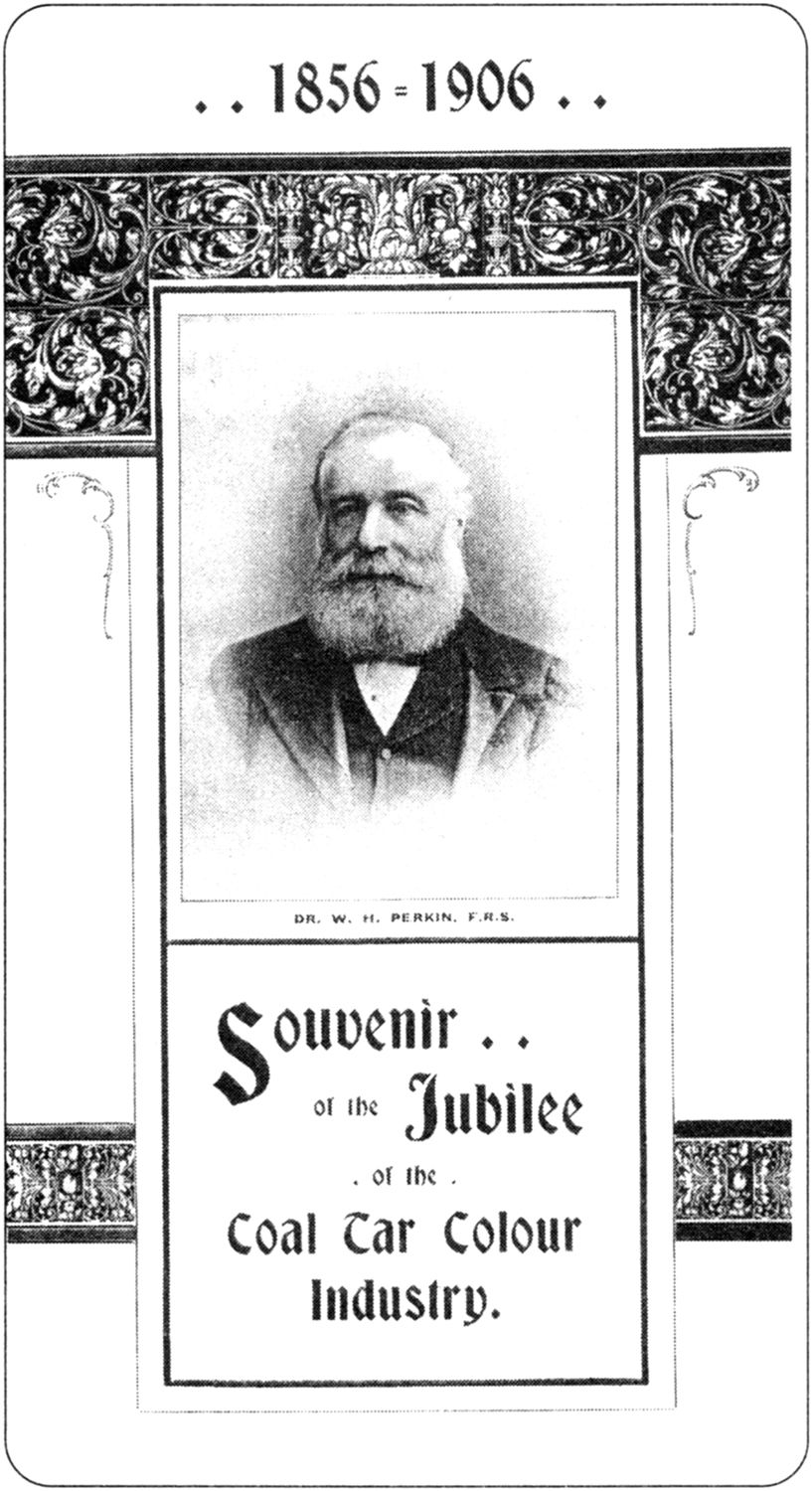

Perkin in 1906 (Science Museum)

Perkins house, The Chestnuts (courtesy the Perkin family)

PLATE 8: Paco Rabanne catwalk model (Chris Moore Agency)

Stained micrograph of the bacteria Mycobacteriumtuberculosis (Science Photo Library)

Despite his immense wealth, Sir William Perkin seldom travelled abroad. He had visited friends and colleagues in Germany and France, and had once been to the United States, but he found the experience tiring and quickly grew weary of sightseeing. Eight days to cross the Atlantic with nothing to do but read and look at the waves. Sometimes the sea made him nauseous.

In the autumn of 1906, at the age of sixty-eight, he resolved to give travelling another chance. On 23 September he boarded RMS Umbria, bound for New York, taking with him his wife Alexandrine and two of their four children. He spent much of the voyage writing in his first-class cabin; he had a speech to give a few days after arrival, and some letters to attend to. He had recently received a request from a chemist in Germany asking for details of his early life for a lecture he hoped to deliver to his students. Perkin was famous now, and each post seemed to bring enquiries about his career and invitations to celebrations.

He wrote in a modest and unflowery style. The first public laboratory I worked in was the Royal College of Chemistry in Oxford Street, London, in 18531856. It wasnt like the great electric laboratories of today, he noted, with your huge booming furnaces. There were no Bunsen burners we had short lengths of iron tube covered with wire gauze. It was a grey place. There were many nasty explosions.

As the Umbria pushed on, newspapers throughout North America excitedly carried the news of Perkins imminent arrival. Famous Chemist Visits Here, announced the SantaAnaEveningBlade. British Invade City Hall, said the NewYorkGlobe. In most cities the very fact that Perkin had boarded a steamship was enough to make the front page, but the coverage was nothing compared to that greeting his arrival.

Perkin and family disembarked in New York, where they were met by Professor Charles Chandler of Columbia University. There is a photograph of them all at the quay in their heavy tweeds and woollen coats, and they dont look particularly thrilled to be there. Im weary, Perkin told one reporter who met him at Professor Chandlers apartment in midtown Manhattan. A few days later, the NewYorkHerald racked up a list of his achievements, and proclaimed : Coal Tar Wizard, Just Arrived in Country, Transmuted Liquid Dross To Gold. In this story, Perkin had been elevated to the status of scientific saint, his merits placed alongside those of Watt and Stephenson, Morse and Bell.

Everyone wanted to meet him. His schedule was frantic. On Saturday night there would be a big dinner in his honour at Delmonicos , New York Citys premier banqueting hall. But before then, there was some flesh-pressing and some sightseeing. On Monday he would be the guest of George F. Kunz, the gem expert at Tiffanys, who said he would escort him and his family around various stores of interest to chemists. The Perkins would then visit the zoo, New York Botanical Garden and the Museum of Art. The next day they were off to the country home, in Floyds Neck, Long Island, of William J. Matheson, a representative of a large German chemical firm. On Wednesday he would spend time with the mayor of New York, George B. McClellan. On Thursday, H. H. Rogers would take them on his yacht for a sail up the Hudson, and the next day it would be the Laurel Hill Chemical Works. The Sunday after the banquet there would be a leisurely evening at the Chemists Club on 55th Street.

Then there was Boston for more of the same, and then Washington DC, where Perkin was due to meet President Roosevelt. The party was then booked in at Niagara Falls, followed by Montreal and Quebec City, and then back to the United States for honorary degrees from Columbia in New York and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore .

Like many tourists before and since, Perkin found that Boston reminded him of English cities, and he especially enjoyed his trip out to Charlestown to see the battleship RhodeIsland. I am greatly looking forward to meeting your President, Perkin said as he boarded the Colonial Express bound for Washington. It is a certain honour, Perkin told everyone who asked all about his great discovery. I was in the laboratory of the German chemist Hofmann , he explained, his comments recorded a day later in the LittleRockGazette. I was then eighteen. While working on an experiment, I failed, and was about to throw a certain black residue away when I thought it might be interesting. The solution of it resulted in a strangely beautiful colour. You know the rest.

*

About 400 people gathered at Delmonicos at 7 p.m. One reporter present noted how If burial in Westminster Abbey is the highest of posthumous honours in the Anglo-Saxon world, we doubt whether a famous Englishman can receive a surer proof of his living apotheosis than when he is entertained by a company of representative Americans at Delmonicos.