Kevin Peraino - A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949

Here you can read online Kevin Peraino - A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Crown, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949

- Author:

- Publisher:Crown

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kevin Peraino: author's other books

Who wrote A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2017 by Kevin Peraino

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Photo insert credits can be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Peraino, Kevin, author.

Title: A force so swift / Kevin Peraino.

Description: First edition. | New York : Crown, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017000979 | ISBN 9780307887238 (hbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesForeign relationsChina. | United StatesPolitics and government19451953. | ChinaPolitics and government19371949. | TaiwanPolitics and government19451975. | ChinaForeign relationsUnited States. | United StatesForeign relationsTaiwan. | TaiwanForeign relationsUnited States.

Classification: LCC E183.8.C5 P525 2017 | DDC 327.73051dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017000979

ISBN9780307887238

Ebook ISBN9780307887252

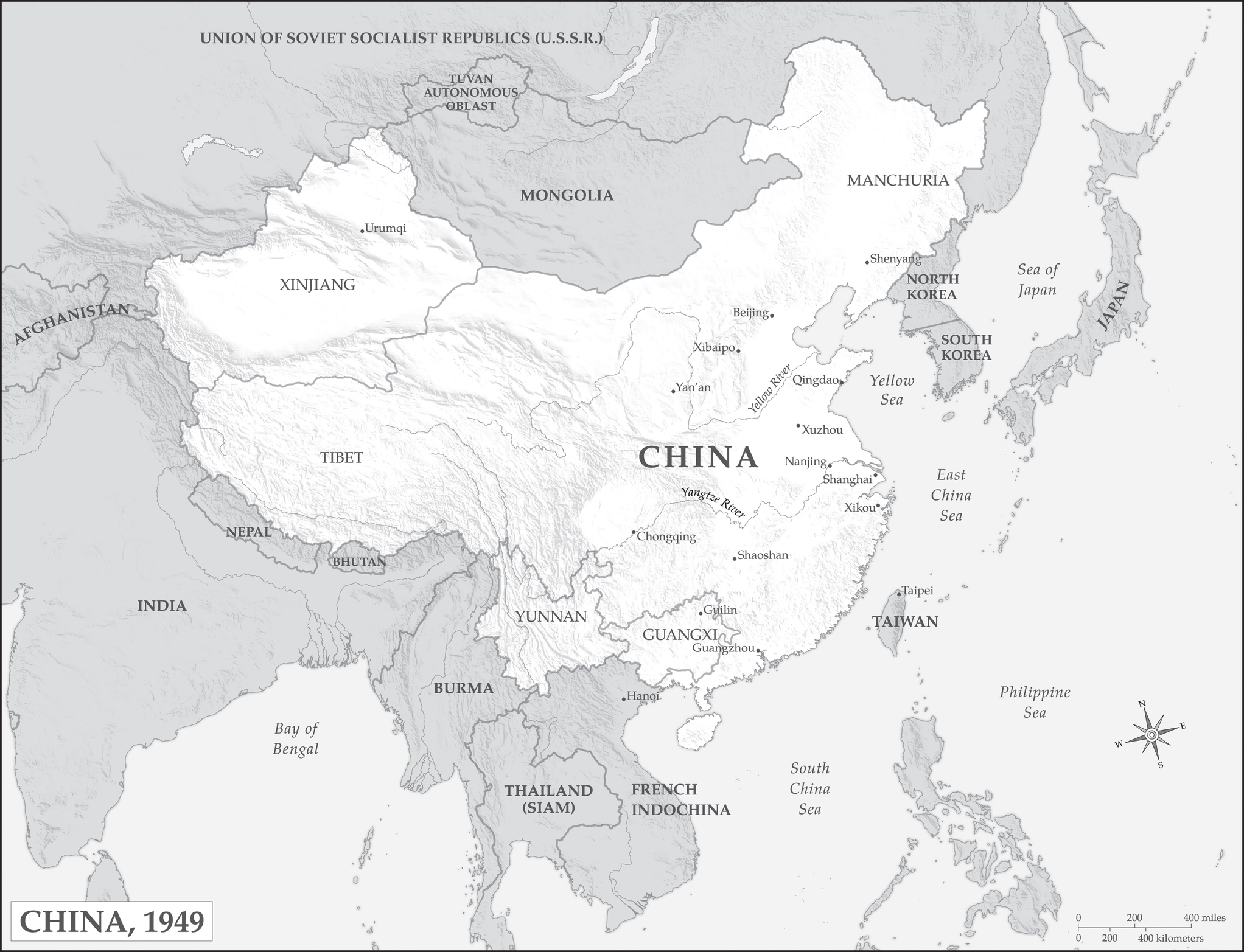

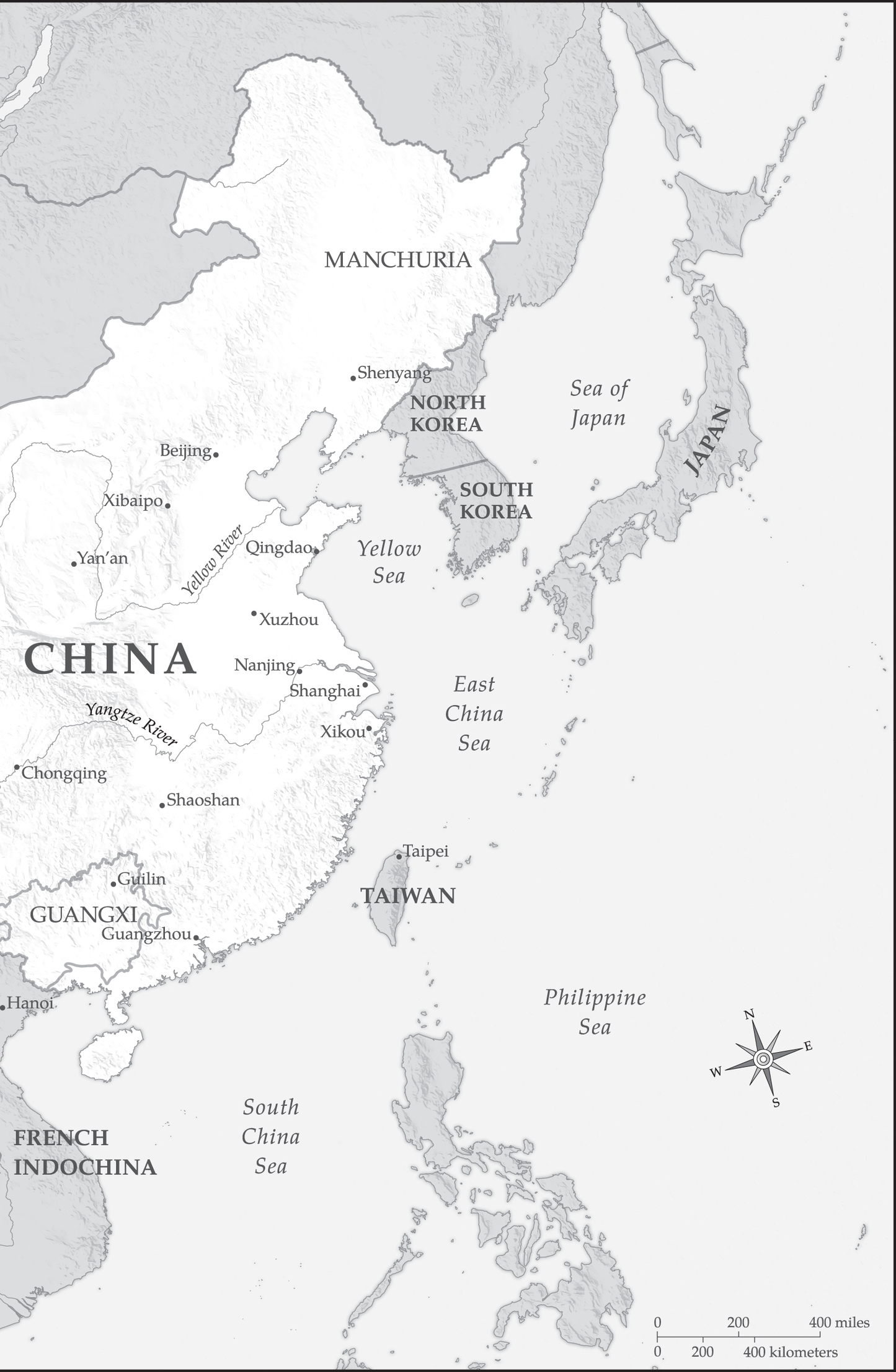

Maps by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

Cover design by Oliver Munday

Cover photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

v4.1

a

In a very short time,

several hundred million peasants

in Chinas central, southern,

and northern provinces

will rise like a fierce wind or tempest,

a force so swift and violent that

no power, however great,

will be able to suppress it.

MAO ZEDONG

Detail left

Detail right

O CTOBER 1, 1949, B EIJING

B odies jostled, elbow to elbow, angling all morning for a spot in the square. Soldiers clomped in the coldtanned, singing as they marched, steel helmets and bayonets under the October sun. Tanks moved in columns two by two; then howitzers, teams of ponies, gunners shouldering mortars and bazookas. On the flagstones, in front of the imperial gate, men and women craned their necks toward a platform above a portrait of Mao Zedong, painted in hues of blue, hanging beside tubes of blue neon. Underneath, a sprinkling of yellow streamers rippled in the crowd. Nearly everything else in the frenzied square was red.

Shortly after three p.m., a tall figure in a dark woolen suit stepped up to a bank of microphones atop the gate. He lifted a sheet of folded paper, pursed his lips, and glanced down at a column of Chinese characters. A double chin rested against his collar; heavy jowls had long since submerged his cheekbones. Although Mao was still only in his mid-fifties, he was not in good health. He rarely went to bed before dawn. For years he had punished his body with a masochistic regimen of stewed pork, tobacco, and barbiturates. Occasionally, overcome by a spell of dizziness, he would suddenly staggerone symptom of the circulatory condition that his doctors called angioneurosis. Still, he had retained into middle age what one acquaintance described as a kind of solid elemental vitalitya kinetic magnetism that photographs could never quite manage to convey.

On this day, Maos speech, delivered in his piping Hunanese, was nothing particularly memorable: a few lines praising the heroes of the revolution and damning the British and American imperialists and their stooges. But the celebration that followed, marking the birth of the Peoples Republic of China, was a cathartic spectacle. Mao pressed a button, the signal to raise the flagyellow stars against a field of crimsonand a band broke into March of the Volunteers, the new national anthem, with its surging chorus of Arise, arise, arise! An artillery battery erupted in salute; a formation of fighter jets slashed across the sky.

The sun set, and the party went on: fireworks raced toward their peaks, rockets of white flamethen fell, smoldering but harmless, into crowds of giddy children. Red gossamer banners billowed in the evening breeze, undulating like enormous jellyfish; to one witness, the British poet William Empson, they possessed a kind of weird intimate emotive effect. Lines of paraders hoisted torches topped with flaming rags; others carried lanterns crafted from red papersome shaped like stars, some like cubes, lit from within by candles or bicycle lamps. Slowly, singing, the glowing procession bled out into the city.

Among the marchers was a boy of sixteen, Chen Yong. He held a small red flickering cube. He had been twelve years old when he joined Maos army, though he had looked even youngera year or two, at least. He had studied Morse code, one of the few jobs for a boy his age, then joined a unit that fought its way through Manchuria. As the long civil war was coming to a close, Chens father had thrown his boy back in school. But on this night no one was studying. The war was over; Mao had won. Chen carried his lantern into the dark.

Nearly seven decades after this celebratory light show, I visited Chen Yong at his home in Beijing, an unfussy apartment block in one of the citys western neighborhoods. Chen was now in his early eighties; his hair had gone white, and a gauzy beard descended from his chin. In his hand, trembling slightly, he clutched a pair of eyeglasses. One inflamed eyelid was nearly closed; a furtive intensity had replaced the calm flat gaze of his teenage years.

One of my favorite parts of researching this booka yearlong chronicle of the Truman Administrations response to Maos victory in 1949was the opportunity to spend time with some of the remaining eyewitnesses to the events of those dramatic twelve months. There are fewer and fewer survivors left; some of the key figures have been dead for four decades and more. The rest are elderly, their memories fading fast. In telling this story I have generally clung to the contemporary documentsthe diaries, memoranda, letters, and newspaper reports that yield the most accurate portrait of that year. Still, I never passed up the opportunity to talk with those who were actually there. There was something magical about these encountersa living connection to a bygone China.

In the summer humidity of his apartment, Chen shuffled slowly across the concrete floor, opened a drawer in his bedside table, and pulled out a black and white photo. In the picture, his younger self wore the padded gray tunic of a Chinese Communist soldiercinched hopefully at the waist, a size or two too big for his teenage frame. As we talked, the emotion of that year seemed as present as it might have been seventy years ago; at one point he quietly began to sing one of his old marching songs. Yet when I pressed him on the granular details of his experiences, he was often at a loss. He would narrow his eyes, looking straight at me, and say with frustration, Its hard to remember. Still, when I asked him how often he thought back to the events of that year, he said, Pretty much all the time. And that, of course, is the great paradox of growing old: the less we can remember, the more time we spend remembering.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949»

Look at similar books to A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.