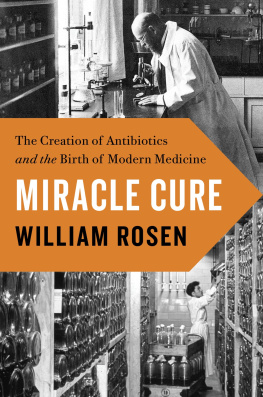

As a surgeon Asklepios became so skilled in his profession that he not only saved lives but even revived the dead; for he had received from Athena the blood that had coursed through the Gorgons veins, the left-side portion of which he used to destroy people, but that on the right he used for their salvation.

THE LIBRARY OF APOLLODORUS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SPECIAL THANKS GO TO Corporate Historian Ruediger Borstel, M.A., whose help at the Bayer Archive in Leverkusen was vital to the success of this work. Michael Frings at Bayer searched out and made available scores of valuable photographs. The Bayer Corporation itself provided travel support for my research in Leverkusen, for which I thank the company in general and Thomas Reinert in particular. At the Pasteur Archives, Stphane Kraxner provided very able and courteous assistance. At the Wellcome Library in London, I received welcome help from Helen Wakely, archivist. I relied as well on the able reference staff at the University of Oregons Knight Library and the Oregon Health and Sciences University. Clifford Mead, head of special collections at Oregon State University, provided insightful and intelligent advice throughout the project.

This book would not have been possible without my agent, Nat Sobel, who put me together with the editors at Harmony. Special thanks here to my editor, Julia Pastore. Maureen Sugden was an exceptional copy editor. Translators were essential for understanding works in French and German, and I was assisted capably by Geraldine Poizat-Newcomb, Yasmin Staunau, Matthias Vogel, and Gerhard Spitteler, as well as my German-savvy son, Jackson Hager. Other scholars who provided support and advice included Suzanne White Junod; John H. Mather, M.D.; Ute Deichmann; Kees Gispen; Brian J. Ford; Frank Ryan; Mary Jo Nye; Charles C. Mann; and Mark L. Plummer.

As every author knows, writing a book can make you temporarily crazy. Thanks to my familyespecially my patient and loving partner in life and writing, Lauren Kesslerfor putting up with this one.

Tom Hager

Eugene, Oregon

INTRODUCTION

I N 1931, humans could fly across oceans and communicate instantaneously around the world. They studied quantum physics and practiced psychoanalysis, suffered mass advertising, got stuck in traffic jams, talked on the phone, erected skyscrapers, and worried about their weight. In Western nations people were cynical and ironic, greedy and thrill-happy, in love with movies and jazz, and enamored of all things new; they were, in most senses, thoroughly modern. But in at least one important way, they had advanced little more than prehistoric humans: They were almost helpless in the face of bacterial infection.

For thousands of years, humans had sought medicines with which they could defeat contagion, and they had slowly, painstakingly, won a few battles: some vaccines to ward off disease, a handful of antitoxins. A drug or two was available that could stop parasitic diseases once they hit, tropical maladies like malaria and sleeping sickness. But the great killers of Europe, North America, and most of Asiapneumonia, plague, tuberculosis, diphtheria, cholera, meningitiswere caused not by parasites but by bacteria, much smaller, far different microorganisms. Nothing on earth could stop a bacterial infection once it started.

It was not for lack of trying. Like the two snakes entwined on the staff of Hermesthe symbol of Western physiciansthe history of medicine comprises two twined skeins of inquiry: understanding how the body works and using that understanding to prevent its destruction. Great strides had been made in the first area. By 1931, physicians had a sophisticated knowledge of how the organs of the body and the systems they createddigestive, hormonal, nervous, and so forthcooperated to create health. They had made a good start on moving from the level of organs and tissues down into the intricacies of molecular biology (a term invented in the mid-1930s). They knew a great deal about what happened to those organs, tissues, and systems when they were hit by disease. But there the knowledge stopped. The great prize eluded them.

That prize, sought since antiquity, was called panacea, a mythical substance that could cure the sick and raise the dead. (Panacea, literally all-healing, was also the name of the ancient Greek goddess of health, daughter of the physician-god Asklepios.) The Egyptians hoped that the art of mummification would lead them to it. The Greeks sang of it. Medieval monks believed that it could be reached through holy relics. Alchemists sought it as the Philosophers Stone, which would not only turn base metals into gold and transform the soul of the seeker but would cure all maladies. It appeared in legends and fairy tales as Achilles spear, Aladdins ring, Fierabrass balsam, Medeas kettle, and Prince Ahmeds apple. Before the scientists took over, generations of magicians, mages, scholars, and snake-oil salesmen had pursued panacea. But no one had found it. Once a bacterial disease took hold in the body, humans in 1931 were as much the prey of the invisible killers as they had been since the beginning of history.

All that was about to change.

I STUMBLED across this storywhich I now consider one of the most important in modern historyquite by accident, a method appropriate for a discovery comprising equal parts skill, mistake, luck, and bullheaded idealism. A reformed scientistI studied medical microbiology for years before deciding that I would rather write about the beautiful, painstaking rigor of bench science than actually do itI was happily thumbing through my dog-eared, spine-sprung copy of Asimovs Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology: The Lives and Achievements of 1510 Great Scientists from Ancient Times to the Present Chronologically Arranged, a delightful candy store of a book for science buffs. I started doing what Isaac Asimov intended his readers to do, I think, when he wrote the book with an emphasis on generous cross-referencing: that is, I began linking the work of one scientist to another, tracing currents of thought across nations and through time. I found my way to the entry on Emil von Behring, the stiff-necked Prussian bacteriologist, which led me to Paul Ehrlich, the Man with the Blue Fingers, whose entry contained a reference to a scientist I had never heard of before, a German physician named Gerhard Domagk. Reading the brief entry on Domagk was the first step on a two-year journey that resulted in this book.

I was intrigued not so much by the manalthough Domagk grew into a more interesting character the more I learnedas by the ways in which his discovery was embedded in and affected so much of what we take for granted in modern medicine. Ours is an age of science; this is an archetypal story of our time.

I am part of that great demographic bulge, the World War II Baby Boom generation, which was the first in history to benefit from birth from the discovery of antibiotics. The impact of this discovery is difficult to overstate. If my parents came down with an ear infection as babies, they were treated with bed rest, painkillers, and sympathy. If I came down with an ear infection as a baby, I got antibiotics. If a cold turned into bronchitis, my parents got more bed rest and anxious vigilance; I got antibiotics. People in my parents generation, as children, could and all too often did die from strep throats, infected cuts, scarlet fever, meningitis, pneumonia, or any number of infectious diseases. I and my classmates survived because of antibiotics. My parents as children, and their parents before them, lost friends and relatives, often at very early ages, to bacterial epidemics that swept through American cities every fall and winter, killing tens of thousands. The suddenness and inevitability of these epidemic deaths, facts of life before the 1930s, were for me historical curiosities, artifacts of another age. Antibiotics virtually eliminated them. In many cases, much-feared diseases of my grandparents dayerysipelas, childbed fever, cellulitishad become so rare they were nearly extinct. I never heard the names.