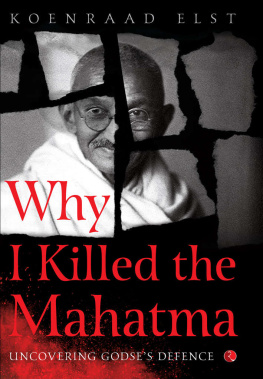

Why

I Killed

the Mahatma

Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2018

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Koenraad Elst 2018

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-81-291-xxxx-x

First impression 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

Dedicated to the memory of Ram Swarup (19201998) and Sita Ram Goel (19212003),

two Gandhian activists who lived through it all and were able to give a balanced judgement of Mahatma Gandhi and his assassin

Contents

Foreword

Historical writing and political purposes are usually inseparable, but a measure of institutional plurality can allow some genuine space for alternative perspectives. Unfortunately, post-independence Indian historical writing came to be dominated by a monolithic political project of progressivism that eventually lost sight of verifiable basic truths. This genre of Indian history and the social sciences more generally reached a nadir, when even its own leftist protagonists ceased to believe in their own apparent goal of promoting social and economic justice. It descended into a crass, self-serving political activism and determination to censor dissenting views challenging their own institutional privileges and intellectual exclusivity. One of the ideological certainties embraced by this coterie of historians has been the imputation of mythical status to an alleged threat of Hindu extremism and its unforgivable complicity in assassinating Mahatma Gandhi.

Historian Dr Koenraad Elst has entered this crucial debate on the murder of the Mahatma with a skilful commentary on the speech of his assassin, Nathuram Godse, to the court that sentenced him to death, the verdict he preferred to imprisonment. Dr Elst takes seriously Nathuram Godses extensive critique of Indias independence struggle, particularly Mahatma Gandhis role in it and its aftermath, but he points out factual errors and exaggerations. He begins with a felicitous excursion into the antecedent context of the Chitpavan community to which Nathuram Godse belonged and its important role in the history of Maharashtra as well as modern India. The elucidation of Godses political testament becomes the methodology adopted by Dr Elst to engage in a wide ranging and thoughtful discussion of the politics and ideology of India in the immediate decades before Independence and the period after its attainment in 1947.

Godses lengthy speech to the court highlights the profoundly political nature of his murder of Gandhi. Nathuram Godse surveys the history of Indias independence struggle and the role of Mahatma Gandhi and judges it an unmitigated disaster in order to justify Gandhis assassination. But he murdered him not merely for what he regarded as Gandhis prior betrayal of Indias Hindus, but his likely interference in favour of the Nizam of Hyderabad whose followers were already violently repressing the Hindu majority he ruled over. In the context of discussing Godses political testament, many issues studiously ignored or wilfully misrepresented by the dominant genre of lssweftist Indian history writing are subject to withering scrutiny. The impressive achievement of Dr Elsts elegant monograph is to highlight the actual ideological and political cleavages that prompted Mahatma Gandhis tragic murder by Godse. A refusal to understand its political rationale lends unsustainable credence to the idea that his assassin was motivated by religious fanaticism and little else besides. On the contrary, Nathuram Godse was a secular nationalist, sharing many of the convictions and prejudices of the dominant independence movement, led by the Congress party. He was steadfastly opposed to religious obscurantism and caste privilege, and sought social and political equality for all Indians in the mould advocated by his mentor, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (also called Veer Savarkar).

Godses condemnation for the murder of Mahatma Gandhi cannot detract from the extraordinary cogency of his critique of Gandhis political strategy throughout the independence struggle and a fundamentally misconceived policy of appeasing Muslims, regardless of long-term consequences. His latter policy merely incited their truculence, and far from eliciting cooperation on a common agenda and national purpose, intensified their separatist tendencies. His perverse support for the Khilafat Movement, opposed by Jinnah himself, was compounded by wilful errors at the Round Table Conference of 193032. He took upon himself the task of representing the Congress alone during the second session without adequate preparation, and eagerly espoused the Communal Award of separate electorates. And by conceding the creation of the province of Sindh in 1931 by severing it from the Bombay Presidency, as a result of Jinnahs threats, guaranteed an eventual separatist outcome. Godse also denounced the Congress strategy of first participating in the provincial governments of 1937 without the Muslim League and then withdrawing hastily from them, thereby losing influence over political developments at a critical juncture. He also censures the bad faith of Gandhis unjust critique of the reformist Arya Samaj and Swami Shraddhanandas social activism and Gandhis shocking failure to condemn his murder by a Muslim.

Nathuram Godse even espoused the very conclusions of the progressive strand of historical writing in independent India that blamed the British for accentuating communalism (i.e. religious division) to perpetuate imperial rule. What he did oppose was the kind of communal privileges he felt Mahatma Gandhi accorded to Muslims, though in the end he accepted them as unavoidable for the pragmatic reason of eliciting Muslim support for a united, independent India.

Of course, Gandhis populism transformed both Congress and Muslim politics into a more volatile mass movement. In the case of Muslim politics, over which the constitutionalist Mohammed Ali Jinnah had presided until 1916 before retiring for a time to his legal practice, Gandhis appeasement helped nurture unequivocal separatism. What Godse implacably opposed was Indias partition, which underlined the failure of Gandhis attempt to appease Muslims. Most of all, Godse was outraged by Gandhis continued solicitude towards them after Partition and despite the horrors being experienced by Hindus inside newly-independent Pakistan. In particular, he was appalled by Gandhis insistence on releasing Pakistans share of accumulated foreign exchange reserves, which Jawaharlal Nehru also counselled Mahatma Gandhi against, (while India was at war with it in Kashmir), because the funds would immediately aid their war effort.

Revealingly, Godse appears to have grasped the imperative to negotiate wisely with the British in order to achieve the intact legacy of a united India. He was critical of the posturing of the Congress that ended in the disastrously misconceived Quit India Movement of 1942 that was quickly succeeded by Gandhis total capitulation. The latter could have meant the abandonment of all democratic pretensions and handing over the governance of independent India to the Muslim League to prevent Partition. Quite clearly, Gandhis assassin was not the raving Hindu lunatic popularly depicted in India, but a thoughtful and intelligent man who was prepared to commit murder. In some respects, Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar was an even fiercer critic of Gandhian appeasement of Muslims, sentiments echoed by no less political giants of India and the Congress like Sri Aurobindo Ghose and Annie Besant.

Next page