Contents

Guide

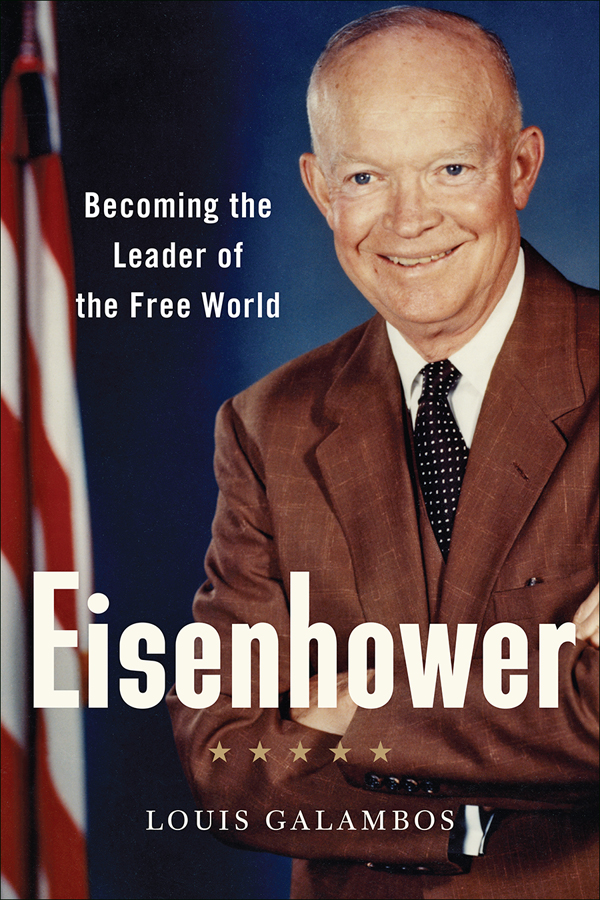

Eisenhower

Louis Galambos

EISENHOWER

Becoming the Leader of the Free World

Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore

2018 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Galambos, Louis.

Title: Eisenhower : becoming the leader of the free world / Louis Galambos.

Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017030371| ISBN 9781421425047 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421425054 (electronic) | ISBN 1421425041 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 142142505X (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 18901969. | PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesPolitics and government19531961. | GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. | World War, 19391945Biography.

Classification: LCC E836 .G35 2018 | DDC 973.921092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030371

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Frontispiece : The Eisenhower family. From left to right: Dwight, father David, Arthur, Earl, Milton with long hair, Edgar, mother Ida, and Roy.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

To all of my students, graduate and undergraduate, over the years

Contents

Preface

We all have a story to tell. Its the story we tell about ourselves and our lives. We tell it to ourselves over and over again, and we tell parts of the story to those who are closest to usour girlfriends or boyfriends, our husbands or wives, our colleagues, our bosses, and those who work for us. We seldom try to tell the whole story because it is very long and terribly detailed. The details may or may not be true. But the stories are nevertheless important because they explain what we do and are crucial to understanding our lives. Our story keeps growing and changing as our lives unwind. Then the story begins to work toward an inevitable conclusion most of us would rather not acknowledge.

Dwight David Ike Eisenhower had a story to tell about his life, a story that changed several times over his long and remarkable career as a military and political leader. His personal story about Ikethat is, his identitychanged decisively seven times as his career unfolded. His status changed, as did his responsibilities, challenges, and reputation. Each change made him a somewhat different person and a different leader, and the major goal of this book is to get at what was changing him, how he was changing, and how it impacted his ability to lead.

Some of the changes in Ikes career were Machiavellian moments. In the two most memorable occasions, he was surprised to find himself the target of this conduct. As he and his leadership style matured, he would find a few occasions to deploy his own cunning and even a touch of duplicity in an effort to achieve his objectives. He of course masked these changes in his leadership behind a sunny, down-home persona and a justly famous smile.

The smile alone, however, was not going to carry him through the dramatic transformations that took place in America and much of the Great corporate farms dominated the markets for agricultural commodities. Businesses such as General Motors were larger, economically speaking, than most of the worlds nations. Technological and scientific developments drove some of these important transformations. Mechanical, electrical, and chemical innovations changed the way Americans got from one place to another, heated and lighted their homes, prevented and treated their illnesses, produced and distributed their essential goods and services, and enjoyed their leisure time.

All of these developments were accelerated by the rise of the professions, which became centers of expertise and important pathways to social mobility. This made access to education even more important than it had been in the nineteenth century. In 1890, the three leading American professions were still law, medicine, and the clergy, but by 1960, more than 11 percent of the workforce had some claim to professional status. From chemical engineers to biological scientists, from statisticians and psychologists to nutritionists, physicists, and accountants, the professions had changed American life and were continuing to splinter into increasingly specialized occupations.

One of the professions that changed significantly was the militarythe profession for which young Ike was trained. It had been a widely disrespected and stunted source of careers in the 1890s, but by the 1960s it was a formidable presence in American life, an institution of central importance to US public policy and to those millions of Americans deeply concerned about Cold War national security. Throughout the twentieth century, the professional soldier worked in and was controlled by a formidable bureaucracy. The military officer was thus more like a clergyman than a private-practice lawyer, more like a professional business manager than a doctor or dentist. Whatever his rank, the soldier was obliged to adjust to awesome technological changes in the weapons of warthe machine gun, the tank, the truck, the jeep, the airplane, radar, sonar, the missile, and finally atomic and nuclear bombs. All decisively altered the way soldiers fought or prepared to fight. Little wonder that a successful officer might by 1961 have an advanced degree in engineering or another discipline. The warrior model was not entirely outdated, but it was increasingly the exception, not the rule. When a leading officer could become secretary of state, something dramatic had changed in the US Armys role at home and Americas role in the world.

Indeed, the global balance of power had shifted in decisive ways five times between the late nineteenth century and Ikes retirement. The rise of Germany and its fall in World War I were followed by the reassertion of German power and the rise of Japan in the 1930s. Another defeat in World War II brought down both Germany and Japan and left the Soviet Union and the United States facing each other in a global struggle for supremacy. By that time, an America that had faced inward for more than a century had moved out into the world, exercising its power and influence in foreign wars and several major revolutions. The United Stateslike all of the nations that experienced industrial revolutionsacquired the new possessions and client states that were customary features of an emerging empire. During the Cold War, America and its allies were arrayed against the Soviet Empire and its communist dominions. By the 1950s, the mainland United States was threatened for the first time since 1815 with a direct and destructive attack by hostile nations. Americas leaders were, with ample justification, fearful of a surprise assault with missiles and nuclear weapons.

At home, the United States was experiencing a series of decisive internal political changes. Like all capitalist nations, America had to cope with an economy that was never at rest. Waves of growth were followed every two decades or so by serious depressions. The worst collapse, the Great Depression of the 1930s, prompted the nation to extend the power and reach of its national administrative state. The foundation for the welfare and regulatory programs of the New Deal had been laid in the Progressive Era, prior to World War I. But the political innovations of the thirties were more dramatic and far-reaching than anything the country had experienced since the adoption in 1787 of the Constitution.