For Beth

Table of Contents

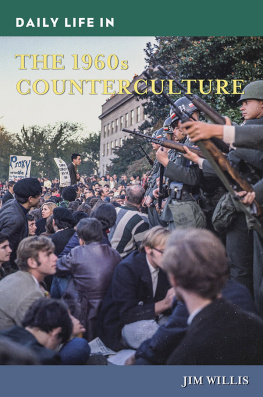

TORN OUT OF TIME, shorn of context, even dimmed by fading memory, images of the 1960s still haunt us, still anger us, still entrance us, still puzzle us. Even those who came of age long after the sixties share the collective memories: the grainy film footage of John F. Kennedy shot down in Dallas, Neil Armstrong stepping onto the moon, Martin Luther King, Jr., telling the world about his dream of racial equality, a naked girl in Vietnam running, screaming, burning with napalm. They are among the most public moments of a very public decade, looped through the mass media in prime-time TV specials, Hollywood films, music video pastiche. In those memories and others lie much of the charge of the 1960s: the possibilities, the grandeur, and always the tragedy. In the 1960s Americans dared to chance grand dreams and they paid for it.

The mission of this book is not to render the high emotions of the 1960s into neutral prose or to turn existential drama into tidy scholarship. But I do place the 1960s back into our history, which links the epochal events of that era to Americans grand projects of the previous decades: the forging of a national system of social provision; the emergence of America as global superpower; the creation of the national security state; and the maturation of a national, consumer-driven, mass-mediated marketplace. These big, ongoing structural developments, I believe, ground most of the explosive events of the 1960s.

I am not suggesting that the events of the 1960s were inevitable or would not have been different if heroes and villains, fools and visionaries of the times had not fought their way onto the historical stage. Any history of the 1960s must paint the brilliant colors of revolt and rupture, of people desperate to make history even as others fought fiercely to stop them. But if the 1960s seemed to many who lived through them a revolutionary time awash in unanticipated and inexplicable conflict, they are, too, very much the culmination of an era that began with the Great Depression and the New Deal and continued with World War II and its aftermath.

Much of my history of the 1960s explains how Americans rapidly developing consumer-based, expert-oriented, nationally managed and internationally integrated economic and political system affected life in the United States. On a domestic political level, the relatively new national system and the affluence that fueled it brought much of American life that had long been left to the control of local elites under national purview. Neither Mississippis legally prescribed racism nor Bible Belt educators practice of starting off each school day with classroom prayer, for example, were by the mid-1960s still unchecked by the federal government. And as Vietnam proved, Americas vast economic and geopolitical interests, as well as the national security apparatus created to serve those interests, made every part of the globe a potential site for massive intervention.

Americas economic and political journey from the dark times of the Great Depression to the go-go years of the 1960s did more than produce new government structures and burgeoning interests abroad. The new economic realities of the postwar years affected Americans sense of values and helped produce what some have called the culture wars of the 1960s, which today still tear at the nations social fabric.

By the mid-twentieth century Americans had to wrestle with two contradictory sets of values. One was necessary for efficient economic production: discipline, delayed gratification, good character, and the acceptance of hard work done in rigidly hierarchical workplaces. The other set of values justified the expansive personal consumption on which economic growth increasingly depended: license, immediate gratification, mutable lifestyle, and an egalitarian, hedonistic pursuit of self-expression. By embracing new consumer-based values, Americans, young and old, often found themselves questioning the production-oriented values of the past and the authorities who espoused them. In sociologist Daniel Bells compelling words, Americans were caught in the cultural contradictions of capitalism. For example, many young, middle-class, white Americans had been raised on the credo that what made America great was its peoples right to decide for themselves what products brought them happiness. Not surprisingly, these same young people rejected authorities right to tell them what music, clothes, and even drugs were culturally and morally acceptable. In the 1960s, market valuesespecially those that insisted on the continuous creative destruction of the old in pursuit of the newripped through American culture.

In the chaotic 1960s marketplace of new ideas, new products, and new responsibilities, a great many Americansand not just radical protesterswere challenged to find new rules and understandings by which to live. Americans questioned the rule makers and rule enforcers who formally and informally governed their lives. Specific events in the 1960slike those associated with the civil rights and liberation movements, the failed war in Vietnam, and the chaotic violence that engulfed Americas citiessprang from Americas changing cultural values, national economic and political system, and international role. Such events also intensified many Americans doubts about the legitimacy and responsibility of their leaders and the authority and wisdom of their cultural arbiters. And since Americans by the 1960s lived in an interconnected world, increasingly governed by national elites, challenges to the status quo were almost impossible to keep localized or out of public view. Instead, every new shock and every new outburst ricocheted throughout the national system and became an issue of collective concern. In the 1960s, issues that at one time could have been treated as local or regional or even personal and private became objects of national scrutiny, judged by national standards.

While manyboth in praise and in criticismhave exaggerated the impact of the 1960s on todays America, those times were explosive and they were the source for many of the changes with which we now live. As a result of what Americans did in the 1960s our country has become a very different place. Personal freedoms have been greatly expandedthough not without causing some to lose their moral compass. Racial and gender hierarchies have been radically subvertedbut not overthrown. New political players and interest groups have multiplied, increasing the nature and scope of public debatebut also fracturing and even polarizing our governing process and cultural life. What Americans did in the 1960s helped bring an earlier era to an end and begin another.

In the 1960sa long time agoAmericans wrestled, as we do today, with fundamental issues of critical national importance. In part we need to understand their struggles because their acts continue to shape our world. Thus we need to judge their dreams and their deeds, and to recount their successes and failures, if we are to understand our own times. But more important, their confrontations, their protest movements, their resentments, their flawed leaders, and their weary martyrs offer us a spectacular drama of a democratic people caught in the grip of their epochas we are caught in oursfighting hard, though with blinkered vision, to bend history to their individual and collective wills. In their rich and moving storya tragedy, I thinkwe find much to stir us and much to contemplate as we struggle to make our own history.

GOOD TIMES

THREE HUNDRED THOUSAND Americans stood shoulder to shoulder. They had been waiting in the cold for hours. Liquor was passed from hand to hand, but the crowd remained good-natured. At last the countdown began: 10 9 8 High above Times Square the illuminated globe began its descent. 4 3 2 1 The crowd roared. The 1960s had begun.