Most of the dialogue sequences in this book come from the veterans themselves, from written sources, diaries or spoken interviews. I have at times changed the tense to make it more immediate. Occasionally, where only basic descriptions of what happened exist, I have recreated small sections of dialogue, attempting to remain true to the characters and their manners of speech.

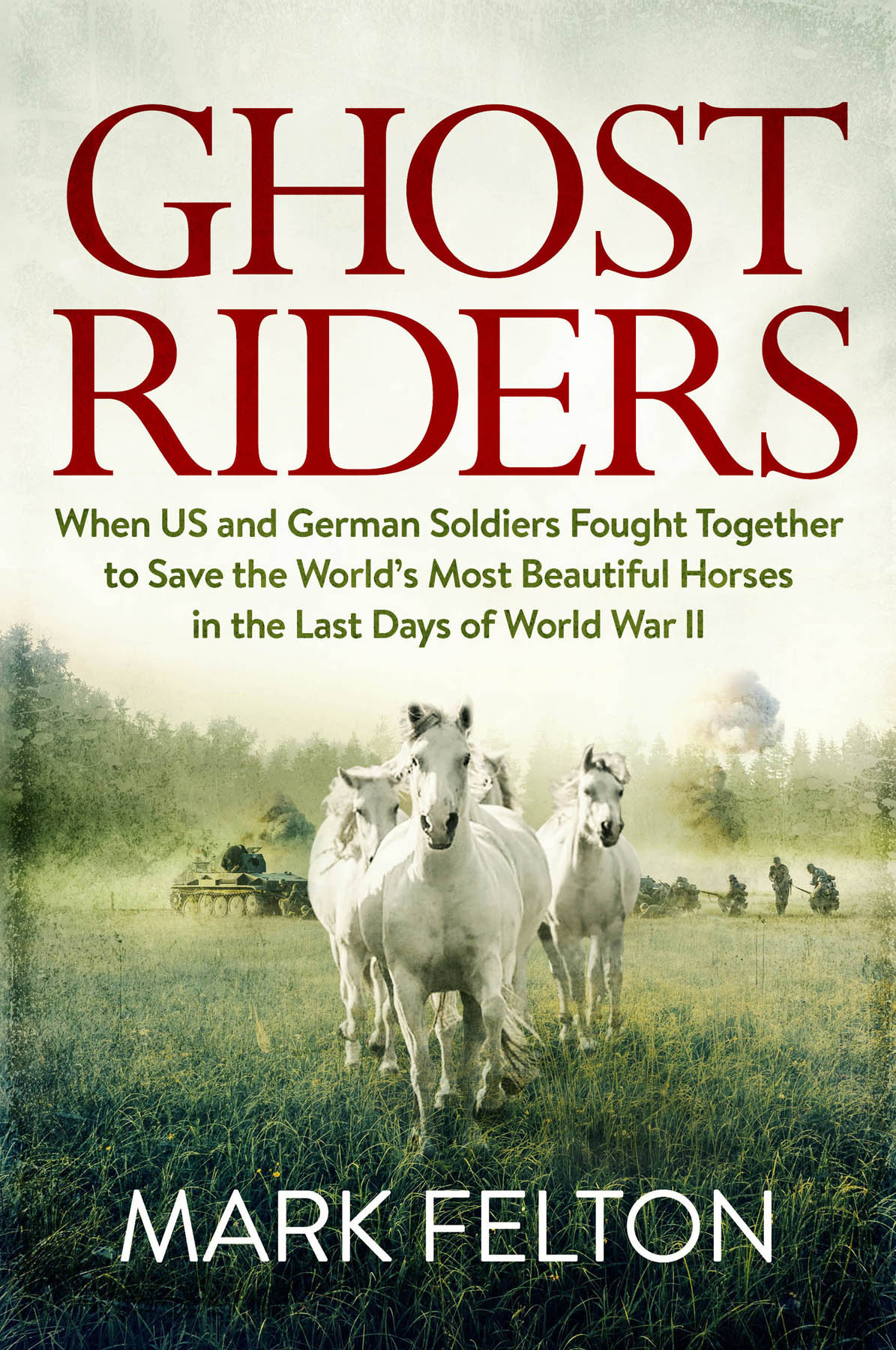

September 10, 1944. The banshee wails of air raid sirens were the first intimation that trouble was coming, their mournful rising and falling sending people scattering to public shelters, subway stations and basements. At the Spanish Riding School, the worlds most famous horse training academy inside Viennas Hofburg Palace, the well-practiced operation of moving the priceless white stallions under cover swung smoothly into action.

The director of the school, the tall, aristocratic-looking 46-year-old Alois Podhajsky burst from his office and immediately began organizing the grooms and riders, who were unlocking stalls and leading out the horses towards a shelter beneath another part of the school. Podhajsky had been born in Mostar, then part of the Hapsburg Empire, and had risen to the rank of colonel in the Austrian Army. Soon after the Nazi takeover of Austria Podhajsky had been appointed director of the Spanish Riding School and become a colonel in the German Army. He was widely known and admired in the worldwide dressage community and had won a bronze medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Now, the institution that he had devoted his life to, and which had endured for nearly 400 years in the heart of Vienna, was in danger of being snuffed out in an afternoon.

Colonel Podhajsky was surprised, and saddened, to see that his stallions were becoming used to the raidseach time the sirens began their awful lament, the horses would move to the doors of their stalls and stand there patiently waiting to be let out, their large and The American bomber streams were targeting Vienna more and more frequently as the strategic bombing campaign across Europe aimed to pulverize the Nazi military-industrial complex. The bombing was inaccurate, with ordnance often landing in the citys historic heart, with its palaces, museums, cathedral and zoo all coming under attack.

The Lipizzaner stallions hooves clattered on the flagstones as they were led from their ornate stables, equipped with marble drinking troughs and smart black stall doors, into a concrete shelter that had been specially designed for these circumstances, their compact, muscular bodies moving without panic, tails held high and heads inquisitive and alert.

Soon, two new and disturbing sounds could be heard, as the sirens wailed mournfully on. The first was the firing of anti-aircraft guns across the city, the sky above filling with dirty brown and black puffs as the shells exploded among the high-flying bomber streams. Then a thumping sound grew progressively louder, much louder than the roaring of the guns: bombs were being released from the bellies of the 344 American B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators that filled the sky.

Podhajsky and the others stared up at the gray concrete roof of their shelter and then down at their equine charges, whose small ears rotated in alarm at the violent sounds, their nostrils flaring as they shuffled their feet, snorted and stamped. The detonations were getting closer, the ground reverberating as the large bombs impacted on their targets. The horses did not panic, thrash about or try to stampede. Podhajsky was pained to see that these fine beasts, representing five centuries of careful breeding and training, cowered just like the humans as the explosions grew louder and louder, lowering their heads to the ground in fear and confusion. On and on came the detonations, the sonic waves making the ground shake and little pieces of debris fall from the ceiling, almost invisible against the Lipizzaners gray-white hair. The humans held the horses heads and shrapnel lacerating the white Baroque faades of the tall buildings, stripping off roof tiles or caving in houses and shops with direct hits.

Inside the white Winter Riding School arena, constructed on the orders of Emperor Charles VI in 1729, the windows that backed the three levels of public seating areas vibrated madly at each detonation before suddenly imploding, shattered glass raining down like ice on to the sanded riding area. The huge and priceless crystal chandeliers that had hung from the 59-foot-tall ceiling were spared, having been packed up on Podhajskys orders. Above the royal box the huge portrait of the emperor, to which generations of riders had raised their birch-branch riding crops in salute, was also gone, leaving just a discolored patch of paintwork where it had hung. Where once Strauss had wafted from speakers, and white and gray stallions had performed with bicorn-hatted riders astride them, now the drone of aircraft engines, the wail of sirens and the thump of further detonations intruded on this unique survival of a bygone age.

When Colonel Podhajsky emerged from the air raid shelter he stood and stared at the broken glass that littered the arena. He shook his head but knew that they had been lucky. It had been the closest raid yet, but the Spanish Riding School had been spared heavy damage. The stallions, as traumatized as the grooms, were led back to their stalls while firemen tackled blazes in nearby streets and medics rushed the wounded to hospital. Podhajsky knew that this could not go on. It was his responsibility to preserve the worlds oldest riding school for Austria. But how?

Colonel Podhajsky had watched as the Nazi state had progressively interfered with the Spanish Riding School. The brood mares that provided the stallions for the school had already been taken from their special stud farm at Piber Castle in Upper Austria The citizens of Vienna had crowded the Winter Riding School for performances or to watch the morning exercises until May. It had provided them with some relief and diversion from the stresses of total war. But Alois Podhajsky would not stop until he had made the Nazis see sense. There was nothing that he could do about the grand buildings and stables, but it was the Lipizzaner stallions that were the heart of the school, its raison dtre. The school was alive and without the stallions the buildings were but museums to a finer and more refined age. The school had to be moved, the horses intensive training continued elsewhere and the legacy of half a millennium given a chance to live.