TALKING BACK TO THE INDIAN ACT

TALKING BACK TO THE INDIAN ACT

CRITICAL READINGS IN SETTLER COLONIAL HISTORIES

Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith

Copyright University of Toronto Press 2018

utorontopress.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kelm, Mary-Ellen, 1964, author

Talking back to the Indian Act : critical readings in settler colonial histories / Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4875-8735-2 (softcover).ISBN 978-1-4875-8736-9 (hardcover).

ISBN 978-1-4875-8737-6 (HTML).ISBN 978-1-4875-8738-3 (uPDF).

1. Canada. Indian Act. 2. Native peoplesLegal status, laws, etc.CanadaHistorySources. 3. Native peoplesCanadaGovernment relationsSources. 4. Native peoplesCanadaHistorySources. I. Smith, Keith D. (Keith Douglas), 1953, author II. Title.

KE7709.2 K45 2018 342.710872 C2018-901475-X

C2018-901476-8

KF8205 K45 2018

We welcome comments and suggestions regarding any aspect of our publicationsplease feel free to contact us at or visit our Internet site at utorontopress.com.

North America | UK, Ireland, and continental Europe |

5201 Dufferin Street | NBN International |

North York, Ontario, Canada, M3H 5T8 | Estover Road, Plymouth, PL6 7PY, UK |

ORDERS PHONE: 44 (0) 1752 202301 |

2250 Military Road | ORDERS FAX: 44 (0) 1752 202333 |

Tonawanda, New York, USA, 14150 | ORDERS E-MAIL: enquiries@nbninternational.com |

ORDERS PHONE: 1-800-565-9523 |

ORDERS FAX: 1-800-221-9985 |

ORDERS E-MAIL: |

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the publisher.

The University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

This book is printed on paper containing 100% post-consumer fibre.

Printed in Canada.

Contents

Figures, Tables, Illustrations, and Maps

Figures

Table

Illustrations

Maps

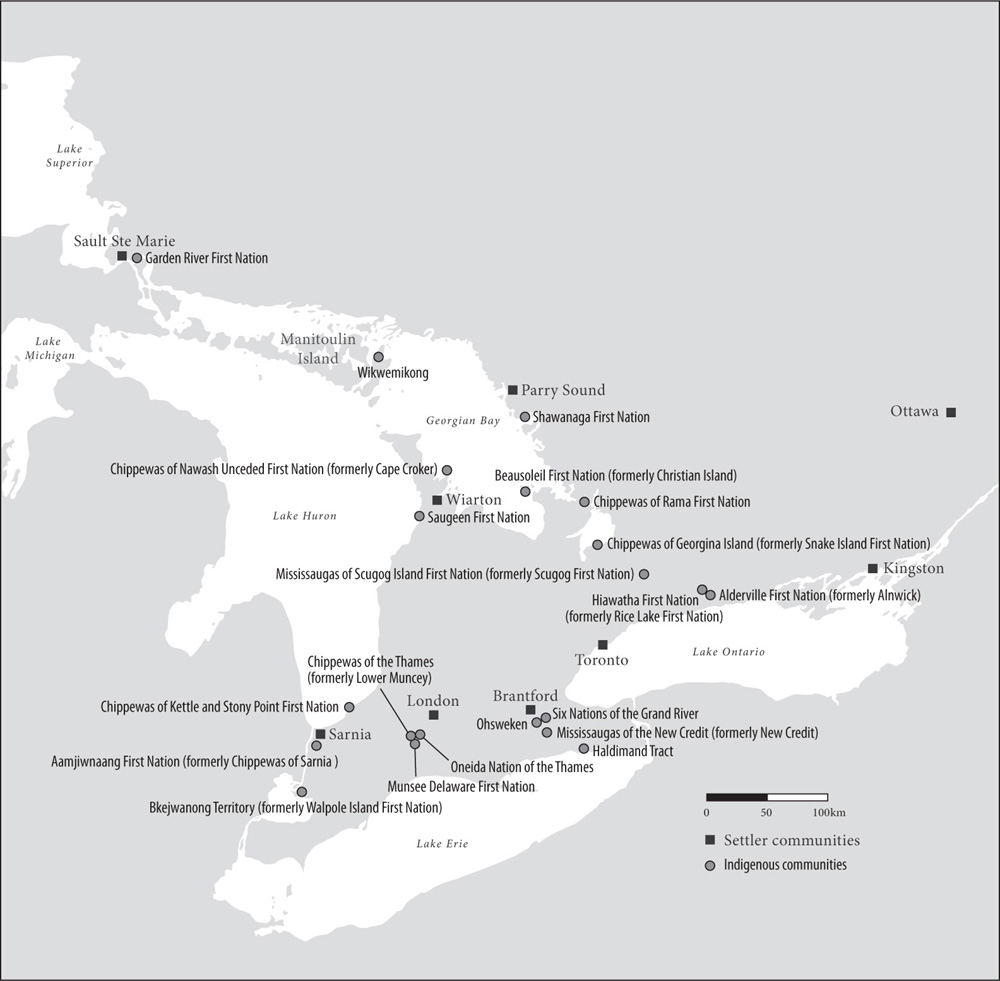

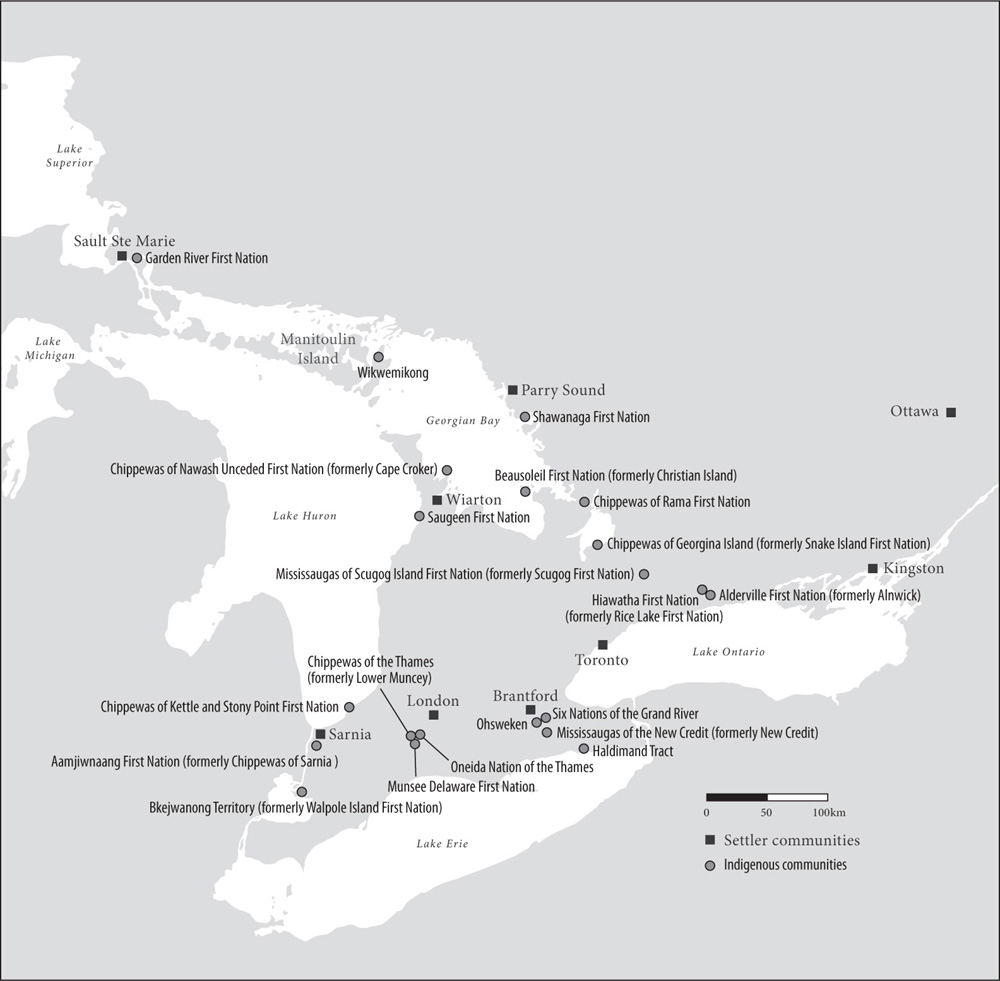

: Ontario Communities of the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario and Quebec

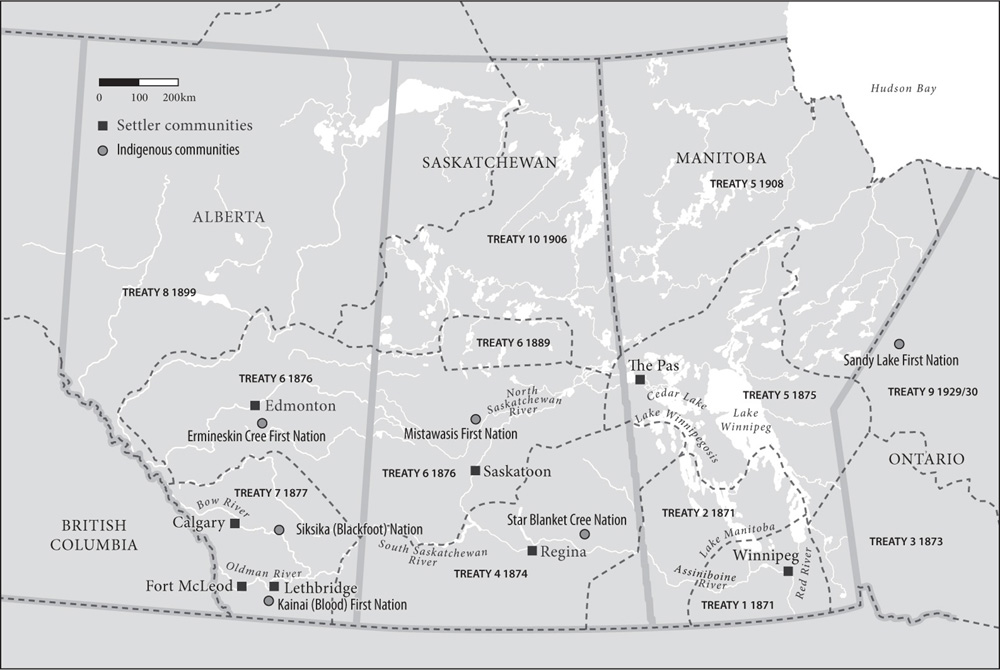

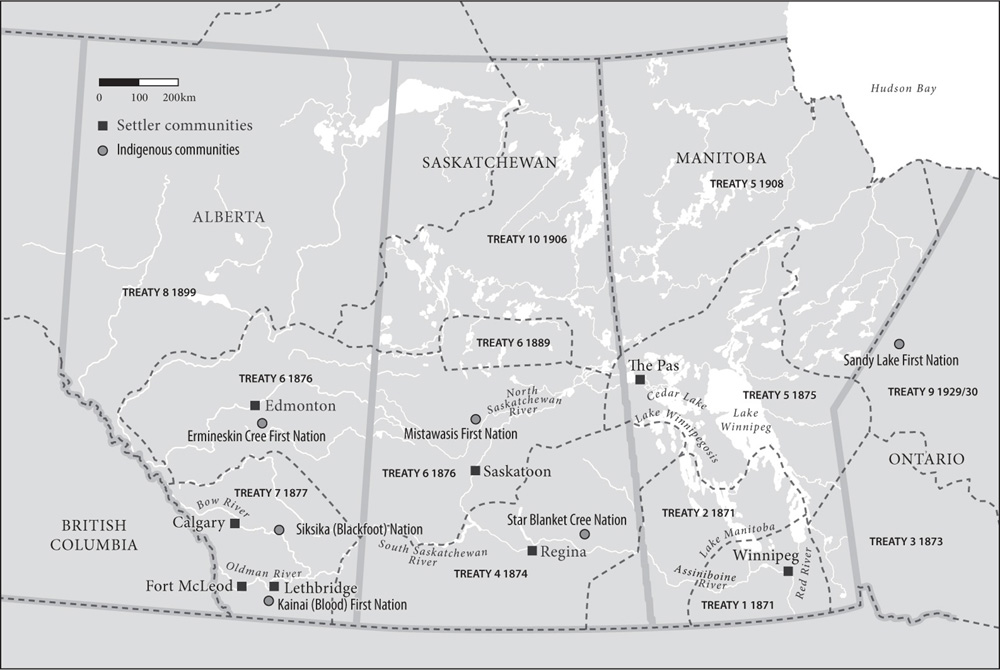

: The North-West

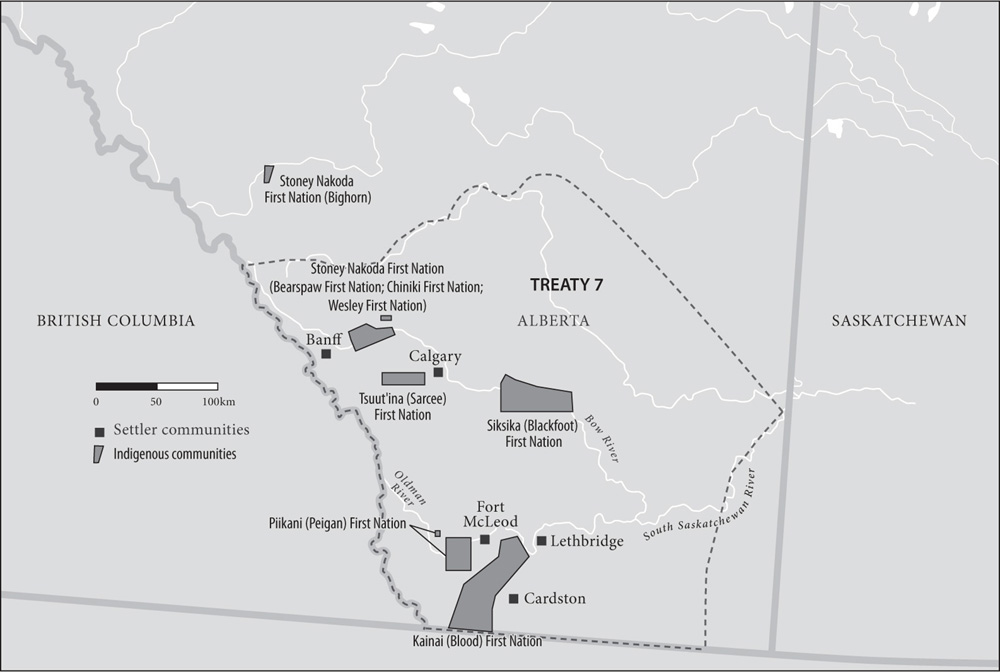

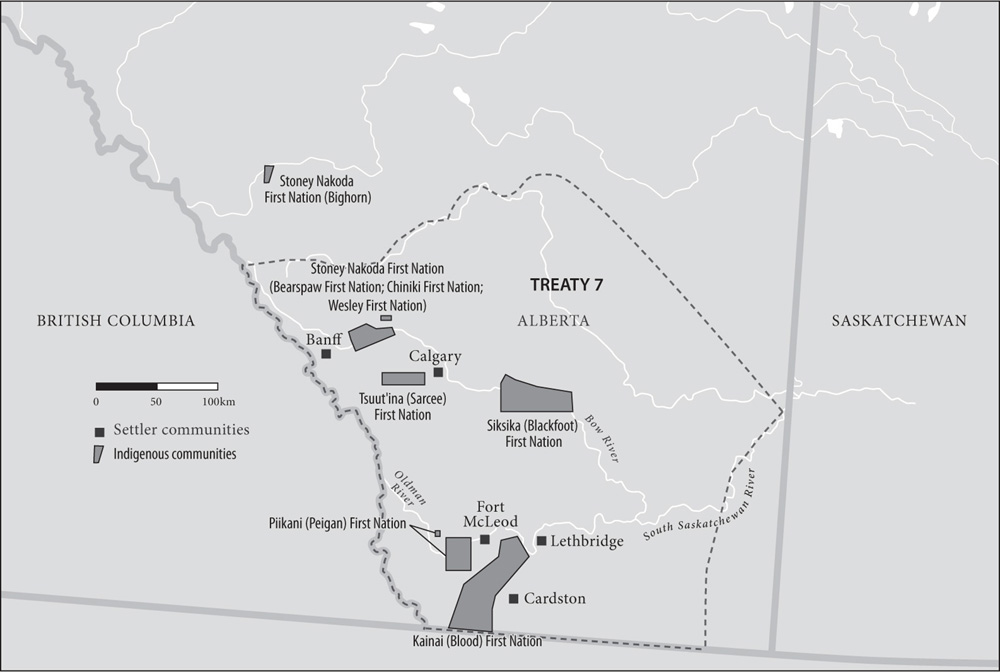

: Treaty 7 Communities

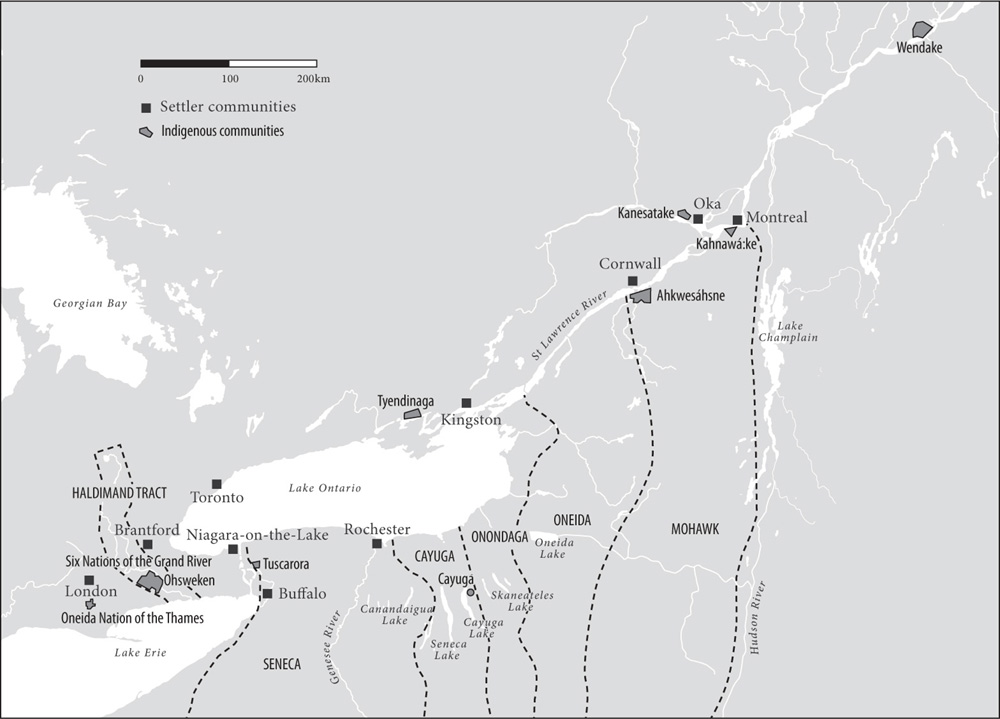

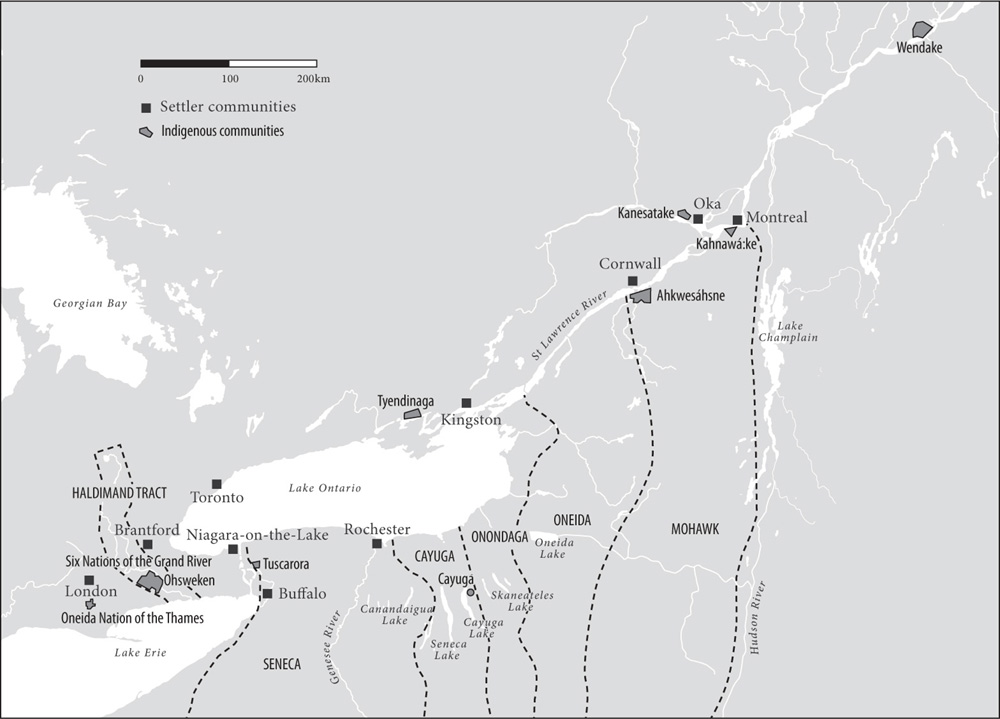

: Haudenosaunee Territories

Introduction

Historians do more than simply read sources; we converse with them. We listen intently to the stories they tell and the silences they allow. We think deeply about the conversations and interchanges that brought our sources into beingthe questions and anxieties, the common sense assumptions, the motives of authors and audiences. We ask questions not so much to call our sources out as false or falsifying but rather to lay bare the remnants of the past embedded within them. As such, the Indian Act reveals much about Canadian politics and what was acceptable to generations of Canadian parliamentarians and the Canadian people who elected them. The Indian Act is, therefore, central to Canadian history.

The Indian Act is also the most important piece of Canadian legislation affecting Indigenous people. It defines who is and who is not considered as Indian under the law. As Mtis scholar Chris Andersen has written, the Indian Act has contributed to race-based policy in Canada. By labelling Mtis and indeed any family seen as half-breed as non-status, it defined status Indian as racially pure without regard for the complexity of Indigenous peoples communities or kinship networks. Although most of its interventions target those it defines as Indian, that very definition impacts all Indigenous people in Canada whether they are considered Indian or not.

The Indian Act has used gender as its primary mechanism of defining Indian status. The act, until 1985, passed Indian status through the father (patrilineally) and for over a hundred years forcibly removed status and membership in reserve communities from women who married non-Indian men. Children of non-Indian men were no longer considered Indians. Revisions to the Indian Act, intended to end the gender discrimination within it, came in 1985, but even after that date, children of women who had married non-status men before 1985 passed on a category of band membership (referred to as 6(2)) that was different than those of children of men who had married non-status women; they received

In 2016, the Liberal government under Justin Trudeau introduced Bill S-3, An Act to Amend the Indian Act in response to the court case Descheneaux v. Canada. In Descheneaux (August 2015), the Superior Court of Qubec agreed with plaintiffs that the Indian Act, as amended by Bill C-3, still discriminated against the descendants of Indigenous women. During legislative review, the Senate called for amendments to S-3 that would ensure that all descendants of Indigenous men and women would be entitled to full 6(1) status. The House of Commons, at first, refused to accept this amendment, but the Senate responded that it would not pass the bill by the Quebec court-imposed deadline of December 22, 2017. Faced with this stand off, the House of Commons crafted its own amendment that would end sex discrimination in the Indian Act after consultation with First Nations. That consultation period was not, however, defined. Bill S-3 passed the House of Commons on December 4, 2017 despite continued concern raised by the opposition that it would still not effectively eliminate sex discrimination. We continue to await the results of consultation and the opportunity to review the impact of Bill S-3 on Indigenous women and their descendants.

Offers of enfranchisement from the mid-nineteenth century onwards worked towards this goal. As early as 1857, the government of the combined colonies of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec) devised mechanisms by which Indigenous men could request citizenship provided they were sober, able to speak and write in either English or French, debt free, and willing to cease being a member of their own communityto cease being an Indian under the law. In exchange, such an individual would receive 20 hectares of land in freehold tenure from his former reserve. Only one man chose to enfranchise under this provision.

Next page