This book made available by the Internet Archive.

TO MY CHILDREN JONATHAN, THOMAS, CATHARINA

I saw how out of Eastern lands A stream of light was flowing And from the West in turn I saw A surge of power growing

Friedrich Riickert, 1814

Comrade, look not on the west: 'Twill have your heart out of your breast; 'Twill take your thoughts and sink them far, Leagues beyond the sunset bar

A. E. Housman, ca. 1898

Ure aghwhylc sceal ende gebidan worolde lifes; wyrce se the mote domes ar deathe

[Each of us must abide the end of this world's life, let him who is able achieve fame before death] Beowulf, ca. 800

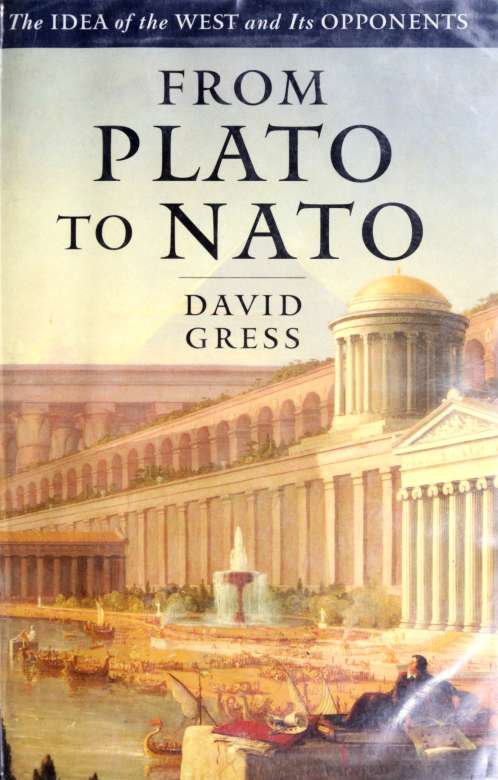

Preface

riedrich Nietzsche said that "every act of writing is an act of impudence." After writing this book I am sharply aware of the multiple truth of that statement. For one thing, I chose an impossibly ambitious subject, namely, the logic of world history and the changing identities of Western civilization. If Arnold Toynbee could not do justice to the first of these topics in twelve thick volumes, who was I to try to address both in twelve chapters? It is true that the book grew somewhat in the writing, but it remains, despite what some may consider its generous bulk, selective and, some may well think, skimpy.

For another thing, this is a work of interpretation and judgment. I have borrowed mercilessly from the thousands of scholar-years that have gone into each of the major issues covered. Where I have borrowed a quote, the source is given in the notes, but I have only selectively annotated ideas or issues. This is partly because to do so fully would have made the notes longer than the text, and partly because many of the notions that I discuss, criticize, or endorse are so much part of my mental inventory that it would be invidious to blame my understanding on one or two people who would thus be, unfairly, singled out at the expense of others who may be truer authors of my views.

A reasonable policy of acknowledgment, in such a situation, might be not to exaggerate the impudence by naming names, beyond those whose actual words I have quoted and who are named in the notes. But such a policy would, in this case, be not so much a matter of holding others harmless as unfair to those whose help was essential, in practical as well as intellectual terms, in keeping this project alive through an unusually rocky history. It was born at one institution, lived its infancy at another, matured in the gap between that and a third, and achieved its final shape at a fourth. Of these four institutions, three were in different countries and continents, and all

xii c^d PREFACE

placed justifiable calls on my time that preempted work on a project that belonged, in full, to none of them. The fact is that this book is the work of what, with apologies to the Romany people, our era calls a "gypsy scholar," that is, of an itinerant worker in an era of cultural as well as institutional downsizing. Undoubtedly, these dislocations and discontinuities revealed aspects of the world to me that benefited the work; just as clearly, and more obviously, they introduced delays and inconveniences.

It was in the late 1970s that I first realized that the key to what we call the West lies in what this book names the sceptical Enlightenment, that is, a liberalism that does not reject history, religion, or human nature, but seeks the conditions of possibility of liberty and prosperity within those givens and not in abstract rights or visions of justice. Years of preoccupation with more immediate issues of policy and contemporary history put that realization on the back burner. The first plan for this book, in 1990, hardly included this line of thought, which came to prominence only as I was writing and it became obvious that the history of Western identity pointed crucially and repeatedly to this open liberalism as the key to its logic and to the logic of its opponents.

Let me now, with apologies to those whom I have not named, thank the following for starting and keeping the ball rolling and bringing me back to it when the outlook seemed dimmest. No one, of course, is responsible for my exploitation or abuse of his or her opinions. My editor at The Free Press, Adam Bellow, first suggested a book on the idea of the West in 1989, and had he not insisted that the book existed in my mind if I would only put my mind to it, it would have remained forever imaginary, as marginal jottings on restaurant notepaper. Especially in the last phases of writing, I have often recalled his encouraging statement that "it's only a book, after all!" I cannot thank him enough for making me, at last, do it.

Exhortations would not have been enough, however, without other forms of help. To the John M. Olin Foundation and its research director, Dr. James E. Piereson, go, therefore, my deepest thanks for research support for this project in 1994-96. Olin, to its credit, keeps many irons in the fire, and in a world where many foundations have chosen, after the Cold War, to go domestic and short term, it deserves praise for keeping a wider view and a broader interest. Next, I want to express my gratitude to the Earhart Foundation and its director of programs, Antony Sullivan, for their support and for maintaining a commitment to questions of religion, world history, and world politics. I thank the master and fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, for admitting me as a visitor in 1993-95, and for conversation and ideas, some of which have made their way into the book. At the college of

^ PREFACE xiii

Michael Oakeshott, I learned to thank his shade, and among those very much alive at Caius and elsewhere in Cambridge, I thank Derek Beales, Tim Blanning, John Casey, Patricia Crone, Brendan Simms, Quentin Skinner, and Joachim Whaley for talk about the West and its enemies. A conversation with Ernest Gellner a few months before his death put me right on his understanding of human social evolution, to which I owe a good part of my general schema. Outside Cambridge but still in England I am grateful for various kinds of inspiration to Noel Malcolm and Norman Stone. It was my good fortune in America to see Malcolm Cowling almost every day for a year or so after he retired from Cambridgea series of encounters that not only prolonged my Cambridge stay by proxy but introduced me to one of the most vital thinkers on the relations of liberal thought and religion. Finally, I do not want to leave Cambridge without paying tribute to a scholar and gentleman who learned of this project, thought it vague and overambitious, but nevertheless on three memorable evenings gave freely of his abundance of knowledge and wisdom about the conditions of liberty and human flourishingthe late Edward Shils.

To the Foreign Policy Research Institute of Philadelphia, which took me in as senior fellow in 1995, I am grateful for this, and for introducing me to an amazing level of intellectual intensity and a solidity of human capital that would be remarkable in an institution ten times its size and wealth. The Institute's president, Harvey Sicherman, and vice president, Alan Luxenberg, made the project theirs in ways that were profoundly heartening and, I dare say, necessary. In particular, the weekends for teachers conducted under the Institute's History Academy forced me to think through some of the topics as if I actually had to explain them to others. In New York, let me also thank Hilton Kramer, who, though he may now regret it, was the first to suggest that I do a book about culture, and Roger Kimball, who has let me offer occasional small servings from the big pot of the West in The New Criterion. Likewise in the United States, I benefited from the conversation, provocation, and insights into things I would not otherwise have thought about of Dennis L. Bark, Mikhail Bernstam, Robert P. George, Stanley Hoffmann, Samuel P. Huntington, Tony Judt, Paul Kurth, Ronald Radosh, and Gail Verdi. Whether these experiences have left any worthwhile traces in the text is for readers to judge. Walter McDougall, as colleague at FPRI and editor of Orbis, allowed me to try out some ideas in the journal. At the Danish Institute of International Affairs (DUPI), my other intellectual home, I thank Niels-Jorgen Nehring, Bertel Heurlin, and Svend Aage Christensen not only for accommodating the last, hectic, and disruptive stages of the project, but