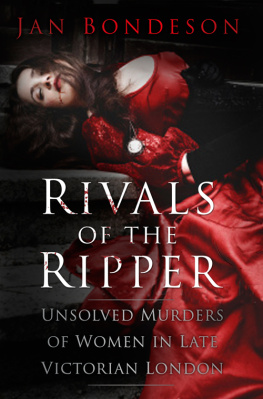

Jan Bondeson - Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London

Here you can read online Jan Bondeson - Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: The History Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London

- Author:

- Publisher:The History Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jan Bondeson: author's other books

Who wrote Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Dream on, dream on

Of bloody deeds and death.

Shakespeare, Richard III

W hen discussing unsolved murders in late Victorian London, most people think of the depredations of Jack the Ripper, the Whitechapel murderer, whose sanguineous exploits have spawned the creation of a small library of books: some of them thoughtful and scholarly works, others little better than publishing hoaxes. Even the most minute details of the Rippers career have been mulled and regurgitated by enthusiastic amateur researchers, helped by all the tools and resources of the Internet Age, and the suspects have ranged from tramps and Colney Hatch inmates to some of the highest in the land.

But in the 1890s, Jack the Ripper was just one of a string of phantom murderers whose unsolved slayings outraged late Victorian Britain. The mysterious Great Coram Street, Burton Crescent and Euston Square murders were talked about with bated breath, and the northern part of Bloomsbury got the unflattering nickname of the murder neighbourhood for its profusion of unsolved mysteries. But whereas Jack the Ripper has strengthened his position in the history of crime, these other London mysteries, although famous in their day, are today largely forgotten.

The aim of this book is to resurrect these unsolved Victorian murder mysteries, and to highlight the handiwork of the Rivals of the Ripper: the spectral killers of gaslit London. The criteria for inclusion are that the victims must have been female, that the murders happened between 1861 and 1897, and that they happened in London. Of the fourteen murders included in this book, eleven happened in central London; there will be three suburban outings: to Kingswood, Eltham and West Ham.

As for cases missing out, I was sad to have to leave out the mysterious shop murder of the butchers wife Mrs Ann Reville in 1881, but this case happened in Slough and thus well outside London.

Care has been taken to analyse the murder mysteries as far as possible, making use of the original police files if extant, of contemporary newspaper coverage of the crimes, and of various other primary and secondary sources. Online genealogical tools have sometimes proven crucial, as have certificates of death and marriage, and a variety of Internet sources. In spite of the obvious difficulties in analysing a century-old murder mystery, it has been possible to produce important clues in quite a number of cases, shedding new light on some fascinating mysteries, and perhaps even hunting down some of the elusive Rivals of the Ripper.

. On the Reville case, see G.B.H. Logan, Guilty or Not Guilty? (London, 1929), 16480, and J. Smith-Hughes, Nine Verdicts on Violence (London, 1956), 122.

. R.M. Gordon, The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London (Jefferson NC, 2002) and M.J. Trow, The Thames Torso Murders (Barnsley, 2011).

. J. Bondeson, Murder Houses of South London (Leicester, 2015), 7983 and 13843.

R ECTORY M URDER , 1861

A strange coincidence, to use the phrase,

By which such things are settled nowadays.

Byron, Don Juan

T oday, Kingswood in Surrey is a large village, situated within the London commuter belt, meaning inflated property prices and trains full to bursting point during peak hours. Back in Georgian times, Kingswood was a sleepy village where little interesting ever happened, but this would change in the 1820s, when the wealthy politician and landowner, Thomas Alcock MP, took up residence in the stately castellated Kingswood Warren. He became Lord of the Manor of Kingswood in 1835 and took an active interest in the welfare of its residents. He made sure that a chapel was built, by subscription, and consecrated in 1836. Since it soon proved too small, the public-spirited Thomas Alcock undertook to have a church built, at his own expense; the church of St Andrew was modelled on a fourteenth-century church in Berkshire and completed in 1852 after four years of work. Importantly for this tale of mystery, Thomas Alcock also made sure that a rectory was constructed, just a quarter of a mile from his own mansion at Kingswood Warren. It was a large red-brick building of traditional design; next to it were the cottages for the village schoolmaster and for the parish clerk.

In 1861, the magnate Thomas Alcock was alive and well, and exercising a benign influence on the inhabitants of Kingswood. The Revd Samuel Barnard Taylor held the living of Kingswood and stayed at the rectory that had been built for him. In May 1861, this gentleman went for a prolonged stay with his father-in-law at Dorking, with his wife, children and servants. On 8 June, he returned to Kingswood, to discharge his clerical duties on the Sunday, but on Monday morning he returned to Dorking, leaving the 55-year-old Mrs Martha Halliday, the wife of the parish clerk, in sole charge of the rectory. She had no objection to sleeping alone on the premises, having done so more than once in the past when Mr Taylor was away with his family. On Monday evening at about 6 p.m., her husband left her to return to his own cottage in the churchyard, about 300yds away.

Kingswood church, from a postcard stamped and posted in 1904. The church still stands and looks much unchanged. (Authors collection)

On the morning of Tuesday 11 June, Mr William Halliday went to see his wife at the rectory. Finding the door open, he went up to his wifes room where he found her lying on the floor in her nightdress, with her hands and feet tied up, a sock crammed into her mouth as a gag and a handkerchief fastened tightly round her head and mouth. She was quite cold and had clearly been dead for several hours.

As soon as the horrified Mr Halliday had made sure that life was extinct, he ran off to alert some neighbours, and soon a party of police was at the rectory. Martha Hallidays dead body had no marks of external violence, so she had clearly choked to death on the gag. The burglars had broken out a pane of glass in a room at the front of the rectory and must have cut themselves in the process, since there were stains of blood on the woodwork. Since the shutters had been securely fastened, they had been unable to get in. They had then gone to the back of the house, only to find that the security-conscious parson had made sure that the ground-floor windows were protected by iron bars. But the burglars took the stump of an old tree, about 12ft long, and put it against a lean-to outhouse. They were able to climb up on to the roof and smash the window of an upstairs bedroom. This was the very room where Mrs Halliday was sleeping, and she must have made an alarm, only to be tied up and gagged by the intruders, with fatal results.

The Kingswood Rectory burglars had searched Mrs Hallidays bedroom, but there was nothing to suggest that they had entered the remainder of the rectory. When the Revd Taylor came home, he searched the house and could report that nothing had been stolen. It was presumed that the burglars had been unnerved by the resistance put up by Mrs Halliday, or perhaps frightened by the slamming of a schoolmasters gate when he returned home to his house nearby shortly before midnight. Interestingly, the burglars turned murderers had left behind a crude beechwood bludgeon, recently made from a large branch from a tree. There was also a bundle of papers tied together with a piece of string. When the latter were examined by the detectives, some very important matters came to light. The six documents were all written in German. First there was an Arbeitsbuch , or service-book, containing credentials for a German labouring man, issued to a certain Johann Carl Franz of Schandau in Upper Saxony. He had last been employed as raftsman by the timber merchant Wilhelm Gotthilf Biemer, but he had only lasted ten days in this job. Then there were the certificates of birth and baptism for Johann Carl Franz, saying that he had been born in 1835, as the illegitimate son of a soldier named Carl Gottlieb Franz, and spent his early years in Soldiers Boys Institute at Strupper. He had been discharged from the army-recruiting depot in 1855, as being unfit to become a soldier. The fourth document was a begging letter, sent by a German named Adolphe Krohn to the opera singer Therese Tietjens, asking for funds to be sent home to Germany, since he was starving and could not find work in London. The response from Mademoiselle Tietjens was apparent from the fifth document, which was a letter from the celebrated singer, giving instructions to Herr Kroll, proprietor of the Hamburg Hotel in America Square, to procure a passage to Hamburg for the carrier of the letter, on her expense. The reason this letter had not been made use of, the police surmised, was that the begging letter writer, Adolphe Krohn, had hoped for some ready cash rather than a return to Germany. The sixth document was a list of names of wealthy people, whom Adolphe Krohn presumably had planned to approach with his begging letters; one of them was Madame Goldsmith, the celebrated singer Jenny Lind.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London»

Look at similar books to Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.