Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Gayle Soucek

All rights reserved

All images courtesy of the authors collection unless otherwise specified.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.614723.274.2

Soucek, Gayle.

Chicago calamities : disaster in the Windy City / Gayle Soucek ; with illustrations by Brian Diskin.

p. cm.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-034-8

1. Disasters--Illinois--Chicago--History. 2. Chicago (Ill.)--History. I. Title.

F548.3.S74 2010

977.311--dc22

2010040434

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to all whose lives were snuffed out too soon by an act of God or man.

Requiescat in pace, Debi, Steve and Roger.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

If you cant explain it simply, you dont understand it well enough.

Albert Einstein

Researching history is sort of like putting together a jigsaw puzzle with some missingand some extrapieces. Sometimes the image is almost complete, but none of the remaining parts fit neatly into the open spaces. When that happens, the best one can do is draw a logical line to fill in the missing brushstrokes and hope that the final picture accurately represents what was intended.

Take, for example, the sinking of the SS Eastland. According to various accounts, the ship was carrying exactly 2,573 passengers and crew. Or 2,753. Or perhaps it was 3,200. And although almost all reports agree that precisely 844 souls perished in the tragedy, a respected newspaper of the day quoted an official on the scene who claimed that more than 900 bodies had been recovered and that they hadnt yet breached the hull. Official records from authorities such as the coroners office can be incomplete or inaccurate, especially for disasters that happened long ago. In some cases, entire families were wiped out; who was left to complain if little Billy or Uncle Joe werent counted? As Lenin once said, A lie told often enough becomes the truth.

Eyewitness accounts arent any more reliable. Many years ago, I had the honor of meeting a survivor from the tragic Our Lady of the Angels fire at a writers conference. She shared with me a horrifying personal memory of watching a friend burn to death in front of her very eyes. I carried that conversation close to my heart, knowing that if I ever wrote about the tragedy someday that I had been gifted with a tiny shard of the shattered memories of that day. As I wrote this book, I routinely flipped through the impersonal casualty lists from the fire, only to discover that the friends name was not recorded under the fatalities. Actually, no one with the exact name was listed as even being in that specific classroom.

Was my acquaintance lying? Of course not. Perhaps the child went by a more casual nickname. There was a similar name in a different classroom. Perhaps in the confusion, children from one room somehow made it to another nearby class in an attempt to escape the beastly inferno. Perhaps my colleague, severely burned and near death herself, was confused about whom had met such a tragic fate just seconds before rescue. Most likely, the historical records are in error. I will never know, because the brave woman died of her long-ago injuries shortly after we met.

With this in mind, please forgive any perceived discrepancies between my accounts and others; in all cases, I have struggled to quote the most reliable sources. I hope once you read this book, you will walk away with some empathy for the victims suffering and a sense of the cultural significance of these disasters. If you do, then I have met my goal.

Part I

FLAMES OF HELL

T HE G REAT C HICAGO F IRE

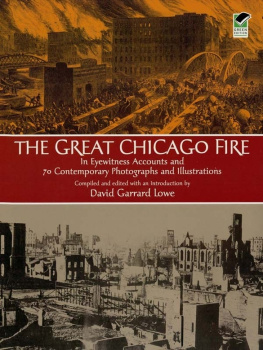

Nobody could see it allno more than one man could see the whole of the Battle of Gettysburg. It was too vast, too swift, too full of smoke, too full of danger, for anybody to see it allIt was simply indescribable in its terrible grandeur.

Horace White, editor in chief, Chicago Tribune

The autumn of 1871 had been one of the driest in memory, the tail-end of a vicious drought that had gripped Chicago and the Great Lakes area since midsummer. Between July and October, only a scant 2.5 inches of rain had fallen on the parched city, a mere trifle in comparison with the normal average of about 14.0 inches for the period. Small fires scampered through the dusty streets, taunting the exhausted men of the fire department who chased them with a mixture of determination and despair. There were too many of themabout twenty in the first week of October aloneand too few resources to bring to bear against the incessant flames. Something had to give.

Everything was as dry as a tinderbox. The city itself was, at that time, a city of wood. Hastily erected tenements of board and log crouched along every avenue. Wooden sidewalks helped pedestrians avoid the usually muddy and swampy streets, the byproduct of building a town on top of a marsh. But now, those streets were as dry as a bone. The unseasonably hot autumn winds swirled dry leaves and dirt in miniature cyclones across the rutted wagon trails, and passing carriages left billowing clouds of dust and grit in their wakes. As people ambled along, twigs crackled and snapped underfoot. Many covered their faces with handkerchiefs, their eyes smarting and lungs burning from the perpetual haze of acrid smoke that hung over the city like a blanket.

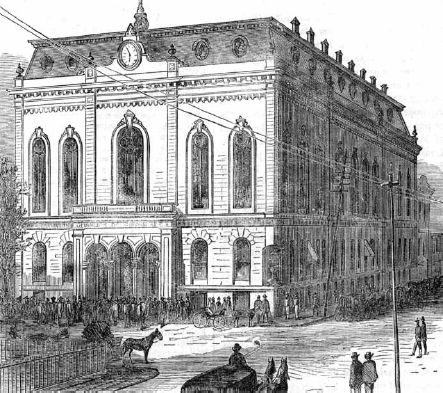

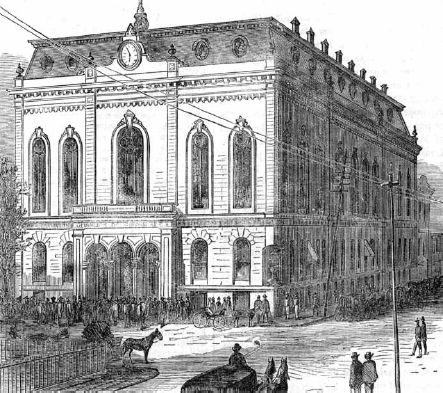

Engraving of the Chamber of Commerce Building before the fire.

On the evening of Sunday, October 8, Patrick and Catherine OLeary and their five children had retired early for the night. Their modest wood-frame home was located at 137 De Koven Street on Chicagos near southwest side, in a working-class neighborhood of mostly poor Irish immigrants. The house actually consisted of two small adjoining cottages, and the OLearys rented the front two-room cottage to the McLaughlin family. In the rear, bordering a small alley, was a barn in which Catherine OLeary kept her livestock. The six cows, one calf and horse and wagon were her livelihoodand the only appreciable wealth her family owned.

People flee over wooden bridges across the Chicago River as the fire approaches. The river did not stop the fire, as expected.

Shortly before 9:00 p.m. that night, a neighbor, Daniel Sullivan, banged on their door to warn them that the barn was on fire. Sullivan had a wooden leg and was known to his neighbors and friends as Peg Leg. He claimed that he had been sitting against a neighbors fence on De Koven Street when he spotted the fire in OLearys barn. According to his later testimony, he ran to the barn in order to rescue the animals and then rushed to awaken the family. He managed to rescue the calf and released one cow that fled and was never found, but the other animals were trapped.

Next page