Contents

Word and Image

Word

and

Image

An Introduction to Early Medieval Art

William]. Diebold

ICON EDTION

First published 2000 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000 by William]. Diebold

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Diebold, William J.

Word and image: an introduction to early medieval art / William J. Diebold.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-3577-9

1. Art, Medieval. 2. Christian art and symbolismMedieval, 5001500. I. Title.

N7850.D53 2000

709'.02dc21

00-025067

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-3879-8 (pbk)

Design by Heather Hutchison

To my father and

to the memory of my mother

This books genesis was an invitation from Lee Ripley Greenfield. Although that original project foundered, I am grateful to her for the invitation and even more grateful to Cass Canfield Jr. for following it up and believing my book worthy of the distinguished imprint he edits. I am also thankful to my students at Reed College, who responded critically to virtually all of the ideas in this book, generated some of them themselves, and tolerated their role as guinea pigs when I tested its organization and contents.

Thanks to all of the museums, libraries, and photo archives that provided photographs, especially those that reduced or waived their fees and therefore made this book possible. The Stillman Drake Fund of Reed College provided crucial support for the photographs and for a research assistant. That assistant, Anne Oravetz, was more talented and thorough than I could have hoped.

Kim Clausing, Abby McGehee Poust, and Isuru Senagama provided invaluable assistance at moments of crisis. Kathy Delfosse was an exemplary copy editor; she saved me from many errors and improved the text in all sorts of ways.

My family, Debby, Joseph, and Abby, not only gave me time to write this book, they often showed more enthusiasm for the process of writing it than did 1.1 first encountered many of the works of art I discuss in the company of my parents, Ruth and Bill Diebold. Without their love, support, encouragement, and example this book would never have come into being.

William J. Diebold

Contents

Introduction

The Character of Early Medieval Art

1 Books for the Illiterate?

Art in an Oral Culture

3 Books for the Illiterate?

Meaning in Early Medieval Art

5 Inscriptions and Images

Artist and Patron in the Early Middle Ages

Conclusion

Brother, what do you think of yhis Idol?

Color (follow p. 4)

983987

Black-and-white

In a letter written in the year 600, Pope Gregory the Great declared, [W]hat writing offers to those who read, a picture offers to those who look; in it they read who do not know letters. Gregorys text marks the chronological beginning of this book, an essay on the nature of visual art in Europe north of the Alps from 600 to 1050. More important, Gregorys letter also provides the books conceptual foundation, the relationship between word and image in early medieval art. That theme is a telling entre to my subject because, in the early Middle Ages, writing and pictures were inextricably linked. The understanding of the word/image relationship was continually shifting, and it will take the entire book to explore it in a nuanced way.

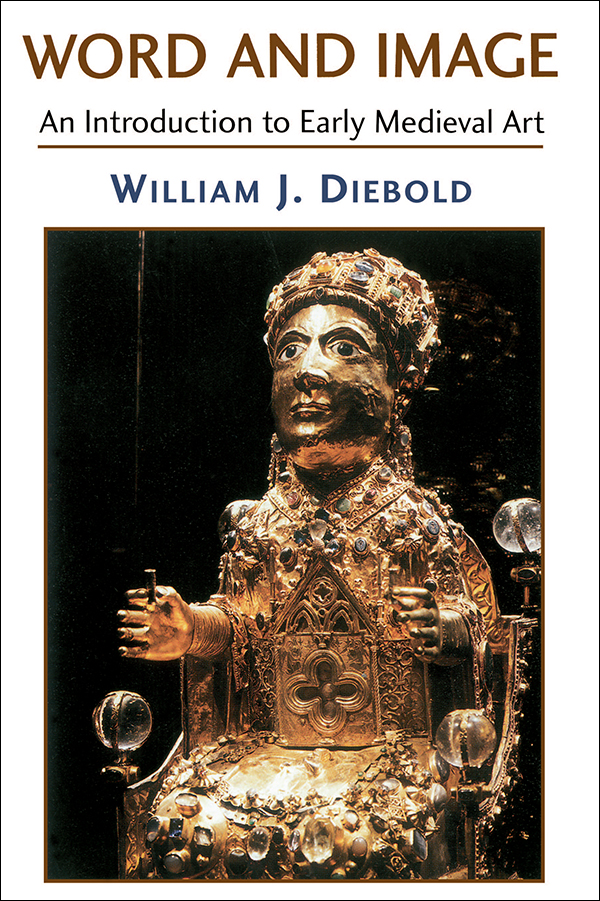

For now, I simply want to warn the reader that this books very premise may seem strange; the modern tendency is to separate the verbal and the visual rather than to link them (many people today, for example, believe that the visual arts come from a hemisphere of the brain entirely distinct from that responsible for words and thoughts). In many ways I hope that this books subject seems unfamiliar, for as much as early medieval art has resonated and continues to resonate with important currents in twentieth-century artistic production, much about it is odd, even bizarre, for the modern viewer; this is much of its appeal. The early medieval conception of art was strange, as were its forms. By the end of this book I will have given that strangeness a context; to begin that process, I want to look closely at an exemplary image, a page from a manuscript of Gregory the Greats letters made in the German city of Trier in the 980s for Egbert, Triers archbishop [Plate I].

This image, made almost four centuries after Gregorys death, attests to the popes importance in the early Middle Ages. Because his letters were valued as statements of church doctrine and as models of epistolary style, they were collected into a registrum, a register; this painting served as a frontispiece to a copy of that text. It shows Gregory working on one of his influential Bible commentaries. As was typical for early medieval authors, the pope does not write the text himself but dictates to a secretary, who transcribes the words with a stylus onto a wooden tablet that has been hollowed out and filled with wax. The early Middle Ages had no other inexpensive writing material: Parchment or vellum, the treated skin of animals (on which this miniature was painted), was a difficult-to-prepare luxury; paper was unknown; and papyrus was almost impossible to obtain in northern Europe because the plant from which it was made grew only in Egypt. According to an early medieval biography of Gregory, one day the scribe, puzzled by Gregorys frequent breaks in dictation, used his stylus to pierce a hole in the curtain that separated him from the pope and saw the white dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregorys shoulder and speaking words of divine wisdom into his ear.

For my subject, the relation of word and image in early medieval art, this painting is almost too good to be true. A luxurious picture used to illustrate a book, it depicts the theologian whose association of images with words was central to the medieval understanding of art. This miniature indicates the crucial place of the word in the Middle Ages, for its subject is that word, both oral (the voices of the dove and of the dictating Gregory) and written (Gregory consults an open manuscript on the lectern in front of him while he holds another closed book in his right hand; the scribe writes on the wax tablet). But the picture also has as its theme vision, the sense without which art does not exist: The scribe, baffled by the absence of words from the popes mouth, cannot solve the mystery with his ears, the organs of hearing; he is forced to pierce the curtain in order to use his eyes, the organs of sight, which in this instance provide better evidence than his ears.