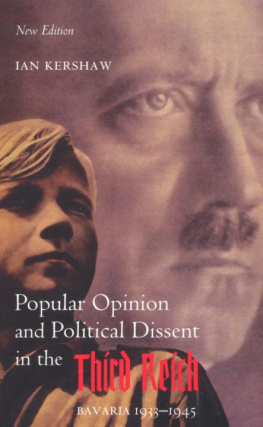

Ian Kershaw

For Betty, David, and Stephen

It is an interesting, but also salutary, feeling to be offered the opportunity to look back and reflect on one's own book from a distance of some years. The distance provides a detachment that it is scarcely feasible to attain at the time of writing. It is, indeed, in some respects a humbling experience to see one's own work as the product of a particular time and a specific set of circumstances, and even more so to realise that it is not a finished product, but merely a contribution to a continuing, and wider, debate that, like a mighty river swallowing a rivulet, consumes it and flows on unabated.

It is twenty years since I wrote the preface to the original edition. I would not want to alter that preface, especially the remarks I made then about how I felt about writing as a non-German describing the position of ordinary people living under the Nazi regime. Equally unchanged are my expressions of personal gratitude to all those to whom I am still indebted for their help and encouragement. But it is appropriate to add a few further comments in this preface to a new edition, on the ways historiography in the area covered by the book has evolved in the twenty-six years or so that have passed since I began the research on which it is based, where the book fits into that historiography, and how my own views have been affected by subsequent research.

But Allen had not systematically studied society in the Lower Saxon town of Northeim (or `Thalburg', to use the pseudonym he deployed in the original edition) after the initial phase of the Nazi takeover of power. That was what I originally had in mind for my project.

My own immersion in the approaches to research and historiography of the Nazi era rapidly followed, and was strongly influenced by the indispensable help and encouragement I received from Martin Broszat and his team engaged on the `Bayern-Projekt', and from his colleagues at the incomparable Institut fur Zeitgeschichte, who gave me all the benefit of their unparalleled expertise on the Third Reich.

The second study, the one presented here, concentrated on the opposite side of the picture, on what ordinary people found to criticise in the Nazi regime, how they had to adjust to new demands on their lives, and how different the recoverable attitudes were from the images of unity and conformity portrayed by Nazi propaganda.

Prior to undertaking the research for the book, I had, as I came to realise, uncritically swallowed images of the monopolistic control of society in `totalitarian' states and based my assumptions on them. I remember how struck and excited I was, therefore, by reports, not just by opponents of the regime but coming from the Nazi authorities themselves, which made it plain that there were often very shallow limits to the penetration of propaganda. They showed, too, how ingrained, highly conservative traditions could prove resistant to Nazi ideological inroads in specific areas where they were directly affected, as, for example, in the attacks on the Christian Churches, while at the same time finding other areas of such ideology which they could very easily accommodate.

The three themes around which I structured the book dissent arising from socio-economic policies, from the assault on the Christian Churches, and from the persecution of the Jews - were devised to reflect my initial hypotheses and findings. Contrary to my own naive assumptions - that the ideological preoccupations of the regime corresponded broadly to those of the mass of the population - what struck me so forcefully from the sources was how little a part seemed to be played in the formation of opinion by the anti-Jewish policy which was so central to the regime, and how large a part by contrast was shaped by resentment at interference in daily `bread and butter' issues, and at attacks on religious tradition and practice. The shortest chapter in the book, the final chapter on `popular opinion and the extermination of the Jews', was meant to reflect what I saw to be an extraordinary unimportance in contemporary popular opinion of events of such centrality to the regime's leadership, and of such obvious meta-historical significance, compared with matters far more mundane and insignificant, but which, unlike the extermination of the Jews, affected people's everyday lives, and preoccupied people so much.

This brief description of how the book came to be written, and what it set out to do, suffices to highlight the areas of historiography in which it might be said to find a place. The first area is, broadly speaking, that of `resistance' (seen in its widest sense), and the related issues of conformity, consensus, and collaboration. The second touches on the problems of social change under Nazism, and the continuities or discontinuities of `everyday life'. And the third, in some ways historiographically semidetached from the other two, is the genesis of the Holocaust - specifically the issue of antisemitism in German society and popular reactions to the persecution of the Jews. I will try in what follows to provide a brief (and doubtless superficial) indication, as I see it, of the ways in which historiography has developed in these areas since my book was initially published, and how my own thinking has been influenced by subsequent research.

I

I need do no more here, therefore, than underline the most important issues.

At the time in the mid-1970s that I began working on popular opinion in Bavaria in the Nazi era, research into and the conceptualisation of German resistance to National Socialism was entering a new phase. Leaving aside the unchanging monolithic approach in the German Democratic Republic, there had been two previous discernible phases in the Federal Republic. Between the end of the war and the 1960s, the emphasis had been placed heavily upon conservative resistance, and the heroism of `the men of the 20 July' - those individuals involved in the 1944 plot against Hitler. In the 1960s, much more attention was paid to working-class resistance, though this concentrated mainly on institutional and organisational studies of socialist and communist underground resistance groups. The new phase that began in the 1970s, into which my book fits, widened the perspective much further, to embrace the behaviour of the mass of ordinary Germans, how they reacted to Nazi rule and were affected by it, their usually partial, less heroic, more `normal', kinds of `everyday' opposition to the elements of regime policy that most directly touched them.