Figure 1. A couple at a dance organized by Strength through Joy in Vienna in 1938

Its like a dream, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary in the summer of 1940, while on a trip to see the sights of occupied Paris. The course of the previous few years seemed to justify his comment. On 30 January 1933, after spectacular electoral successes, the National Socialists had come to power in Germany. They had then seized and extended that power. Political opponents and minorities had been uncompromisingly excluded from the new national community. The regime had prepared single-mindedly for war and had been waging it ruthlessly and effectively since 1 September 1939. The ambitions of the Propaganda Minister and of millions of his likeminded compatriots were at first fulfilleduntil they became hungry for more. The Third Reich presented itself as a contrast to life during the Weimar Republic, which many Germans regarded as depressing and sordid. The Nazis aimed to be more imaginative than the democrats and philistines they despised. They did not merely indulge in flights of fancy, however; they created a new realityfrom the SA rallies in 1930 to the Wehrmachts victories over Poland and France a decade later. Step by step they were transforming the lives of Germans and of all Europeans in a manner radical enough to fulfil Nazi dreams.

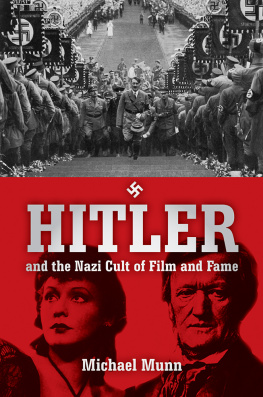

For the real or supposed enemies of the Third Reich, on the other hand, life was not like a dream. Those persecuted spoke instead about nightmares and imagined being free again. Reservations about the Nazis and doubts about the substance behind their promises were not confined to marginalized groups. Nevertheless, millions of Germans not only came to terms with the Third Reich, but hoped it would fulfil their desires. The couple shown in the image preceding this introduction were presumably not thinking about politics, even if a swastika flag is visible in the background. Their dreams for the future may have been purely private. What is certain is that their lives had already undergone fundamental changes, in part because many leisure activities in the Third Reich were provided by the Nazi organization Strength Through Joy and also because they were Viennese and since March 1938, four months before this picture was taken, Austria had been annexed to the German Reich.

The motif of the dream provides a way into the subject of this book, for it was culture that gave expression to the desires and imaginings that were so important to the history of the Third Reich. As early as the later nineteenth century vlkisch (ethnic nationalist, see Glossary) journalists and writers had envisioned a new world in which Germans rediscovered their supposed Teutonic origins and rose to be the rulers of Europe. Richard Wagners operas had used an aesthetically innovative form to recount the stories of heroes who rebelled against a hostile world and either triumphed or perished in the process. Such idealized projections were supplemented in the first decades of the twentieth century by new dreams of being able to restructure whole societies by means of modern media, technologies, and scientific methods. These varied phantasies exerted a considerable influence on Adolf Hitlers thinking as well as on that of Joseph Goebbels and many other National Socialists. Between 1933 and 1945 they left their mark on films, plays, journals, posters, and radio broadcasts. Culture was to mediate ideas to their Volksgenossen (comrades in the German national community, hereafter national comrades) that only a few years before had seemed outlandish and divorced from reality: ideas of Germany as a world power free of Jews and the mentally handicapped.

Culture in the Third Reich had another, less overtly Nazi aspect, however. What was performed on the stage or played in the concert hall or exhibited in a museum derived for the most part from the brgerlich (bourgeois, see Glossary) canon of the nineteenth century and was more conservative than radical. Although the modern media were used for propaganda, each followed the prevailing taste: cinemas showed romances and comedies, the radio broadcast popular music, magazines published attractive features with photos. Bourgeois and popular culture were important precisely because many unpolitical and even many right-wing Germans only partially adopted Nazi ideology. Goebbels himself knew that national comrades on the one hand longed for continuity and on the other sought new opportunities as consumers. Culture, therefore, had the task of promoting renewal and generating willingness to engage. Music, theatre, and film had to be experiences that subtly transmitted Nazi messages, while at the same time reassuring and distracting the more sceptical Germans.

The fact that Nazi phantasies were so ambitious made their artistic realization more difficult. Of course, there were paintings of strapping peasants and fecund women, and Thingspiele (historical pageants) were staged that encouraged the audience to identify emotionally with national renewal, but they appealed only to a minority of Germans and thus were fairly useless as propaganda. Efforts to introduce innovation along vlkisch lines were often frustrated by institutional rivalries or by personal animosities among National Socialists. In addition, influential political figures in the Third Reich, foremost among them Hitler himself, clung to traditional ideas of German culture in part with an eye to national prestige, but also from the urge to present a favourable public image. It was thus hard to define any genuinely National Socialist culture. It gained any distinctiveness it had on the one hand by contrast with the Jews, who were excluded from even the smallest symphony orchestra or theatre company in the Third Reich, and on the other hand from the regimes imperial pretensions. Even before 1939 these pretensions influenced public architecture and went on to set the tone during the war years. For there was now an opportunity to realize a further dream: the dream of German cultural dominance over Europe. The methods used to achieve this included all-out propaganda, economic pressure, and naked violence, particularly aimed at the Jewish minority, whose cultural and physical presence was to be eliminated not only in Germany itself but also elsewhere in Europe.