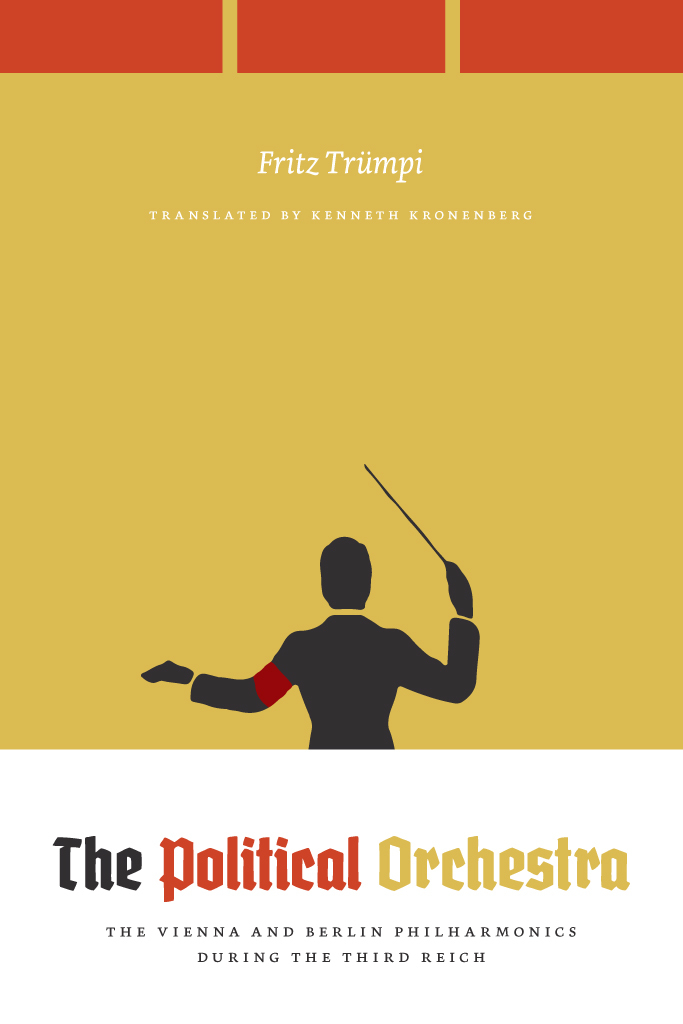

The Political Orchestra

The Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics during the Third Reich

FRITZ TRMPI

Translated by Kenneth Kronenberg

The University of Chicago

Chicago and London

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften InternationalTranslation Funding for Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers and Booksellers Association).

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-25139-4 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-25142-4 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226251424.001.0001

Originally published as Politisierte Orchester: Die Wiener Philharmoniker und das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester im Nationalsozialismus. 2011 by Bhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG. Wien Kln Weimar.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Trmpi, Fritz, author. | Kronenberg, Kenneth, 1946 translator.

Title: The political orchestra : the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics during the Third Reich / Fritz Trmpi ; translated by Kenneth Kronenberg.

Other titles: Politisierte Orchester. English

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016012941 | ISBN 9780226251394 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226251424 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Wiener PhilharmonikerPolitical activityHistory20th century. | Berliner PhilharmonikerPolitical activityHistory20th century. | National socialism and musicAustria. | National socialism and music. | OrchestraPolitical activityHistory20th century. | MusicPolitical aspectsAustriaHistory20th century. | MusicPolitical aspectsGermanyHistory20th century.

Classification: lcc ml28.v4 w54413 2016 | ddc 784.206/043155dc23 lc record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012941

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Let me state my point by the method of exaggeration: my aversion from music rests on political grounds. Hans Castorp could not refrain from slapping his knee as he exclaimed that never in all his life before had he heard the like.

THOMAS MANN , The Magic Mountain

So who was worse? The Berliners or the Viennese? And was Wagner the only composer they performed? But that was under Furtwngler, wasnt it? The subject of my book elicited considerable curiosity in Vienna, giving rise to these and similar questions. There were also half-joking warnings, such as, Now dont you go denouncing my Philharmonic! or a heated, You go show it to this Nazi orchestra! Colleagues in Berlin, on the other hand, while not uninterested, often expressed their curiosity in more uninvolved and neutral terms: Well, that sounds interesting. Although the people in Vienna to whom I talked generally had a much more immediate relationship to the Vienna Philharmonicboth positive and negativemy friends in Berlin were less interested in the Berlin Philharmonic as such than in the topic of music under National Socialism in general.

These very different responses point to the divergent symbolic valences of the two orchestras: for the Viennese, the Vienna Philharmonic is emotionally charged in a way that the Berlin Philharmonic simply is not in Berlin. That the Viennese public would elaborate a natural monopoly of musicality, as Theodor Adorno once formulated it, became clear to me in the process of researching and writing this book in these two cities.

These days, one clear difference between the two orchestras is in their representation in the media. The Berlin Philharmonic is viewed as the embodiment of a German sound, and it is both viewed within a national context and seen as representing the nation to itself and the world. The Vienna Philharmonic, by contrast, is associated with all that is Vienna and with Vienna as the music city par excellence.

In 2006 a hot debate erupted over the German sound of the Berlin Philharmonic, which emerged from a polemic against the principal conductor of

On the occasion of a concert with the Berlin Philharmonic, the Finnish conductor Sakari Oramo explained, with more than a little admiration, what this German sound consisted of: First of all, it has to do with a particular earnestness of performance, by which I do not necessarily mean strictness. But the German symphonic tradition lays claim to a philosophical access to the world. This includes brilliance and a particular madness that can be observed in German conductors. German madness breaks through barriers, not to destroy something but rather to make it accessible. It is a madness that makes everything expressive.

The vast majority of the numerous publications that have examined this German sound from a musical perspective have echoed such essentialist explanations. However, a few writers have at least partially viewed it as a construct. For example, the conductor Daniel Barenboim, tried to teach his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra how to produce the German sound as follows: I can explain to you precisely what one has to do so that an orchestra will produce this German sound. It depends on how one begins a tone. Not always accentuated and not hard. It also depends on maintaining the tone to the end. That one does not change its character during a rhythmic figure. And if one encounters sixteenths or rapid eighths, that one does not automatically play with emphasis. Thats when I say, leave your eighths machine at home. Not: Takatakatakataka. For Barenboim, too, the German sound had quite simply become the standard of good music-making.

The Vienna Philharmonic, by contrast, hews neither to the German sound nor even an Austrian one. It has its own Vienna sound. The orchestras website makes clear that, contrary to international practices, the Vienna Philharmonic continues to play older types of instruments. And this seeming reorientation is in some respects significant: an historical decoding of these seemingly innocently yoked wordsVienna soundof which this book frequently avails itself, reveals their political content, and it seems more than likely that the orchestra has in the intervening years become fully conscious of their implications.

Empirical Vienna sound researchVienna boasts its own Institute of Music Acoustics, which is attached to the University of Music and Performing Arts Viennahas, among other things, tried to demonstrate by means of sound experiments that what is distinctly Viennese about the music-making of the Vienna Philharmonic can be isolated and identified:

In order to determine whether what is distinctly Viennese is recognizable on recordings, a large-scale scientific study was conducted in which hundreds of professional musicians, amateur musicians, music students, and music lovers took part. In addition to more than 500 Austrians, groups of musicians in Athens, Paris, Warsaw, and Prague also responded to the sound questionnaire, as did colleagues at Deutsche Grammophon in Berlin and Hamburg. The question was whether it was possible to distinguish between two identical passages of music which had been played by the Vienna Philharmonic and another orchestra, and if possible, to name the characteristics that distinguished the Viennese orchestra.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).