Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Illusions of Emancipation

THE LITTLEFIELD HISTORY OF THE CIVIL WAR ERA

Gary W. Gallagher and T. Michael Parrish, editors

This book was supported by the Littlefield Fund for Southern History, University of Texas Libraries

This landmark sixteen-volume series, featuring books by some of todays most respected Civil War historians, surveys the conflict from the earliest rumblings of disunion through the Reconstruction era. A joint project of UNC Press and the Littlefield Fund for Southern History, University of Texas Libraries, the series offers an unparalleled comprehensive narrative of this defining era in U.S. history.

Illusions of Emancipation

The Pursuit of Freedom and Equality in the Twilight of Slavery

JOSEPH P. REIDY

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

2019 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Adobe Text Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reidy, Joseph P. (Joseph Patrick), 1948 author.

Title: Illusions of emancipation : the pursuit of freedom and equality in the twilight of slavery / Joseph P. Reidy.

Other titles: Littlefield history of the Civil War era.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Series: The Littlefield history of the civil war era | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024859| ISBN 9781469648361 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469648378 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : SlavesEmancipationUnited StatesHistory. | SlaveryUnited StatesHistory19th century. | African AmericansSocial conditionsHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC E 441 . R 35 2019 | DDC 305.896/07309034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024859

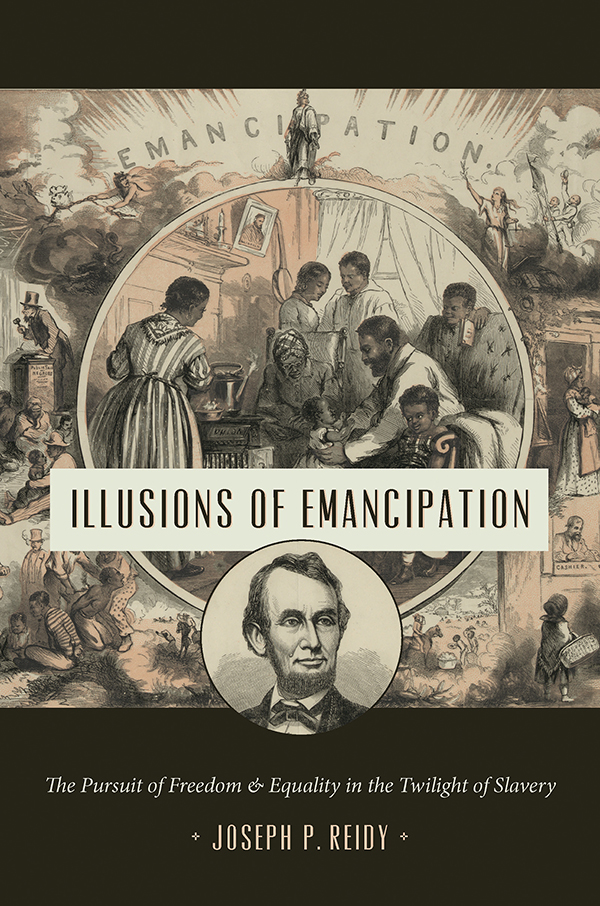

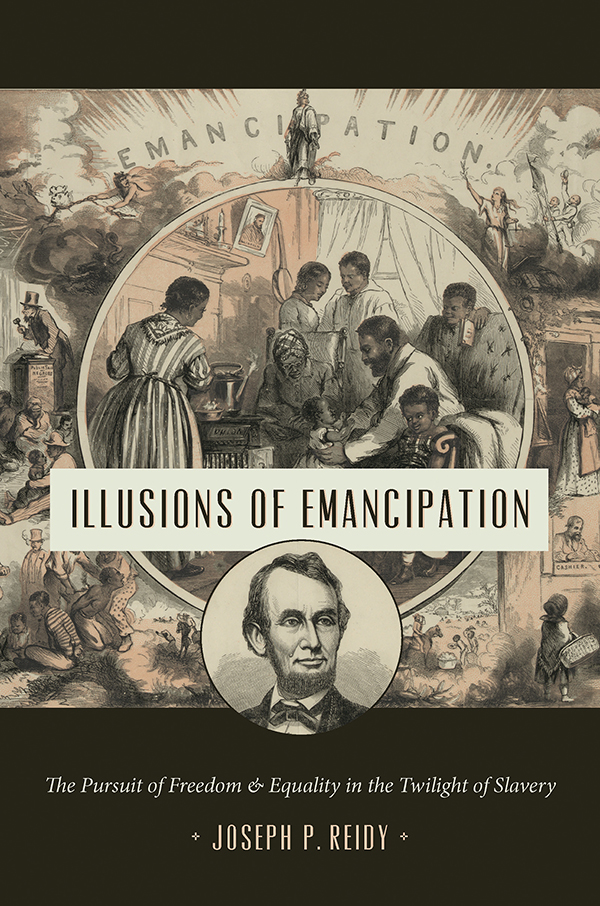

Jacket illustrations: front, Emancipation by Thomas Nast (courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03898); back, Fugitive African Americans Fording the Rappahannock River, Va. by Timothy OSullivan (courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpb-00218).

For Patricia, our children, and our grandchildren

Contents

Figures

Emancipation Monument ,

Forever Free ,

Watch Meeting ,

Colored Army Teamsters ,

Gordon ,

Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana ,

Private Hubbard Pryor, before enlistment,

Private Hubbard Pryor, after enlistment,

Franchise. And Not This Man? ,

Scotts Great Snake ,

The Civil War, 18611865 ,

Stampede of Slaves from Hampton to Fortress Monroe ,

Topographical Map of the Original District of Columbia and Environs ,

Letter of Spotswood Rice,

Contrabands aboard U.S. Ship Vermont, Port Royal, South Carolina ,

Deck of the Gunboat Hunchback ,

Fugitive African Americans Fording the Rappahannock ,

On to Liberty ,

Emancipation ,

Freedmans Village map,

Freedmans Village , Arlington, Virginia ,

The First Vote ,

Office for Freedmen, Beaufort, South Carolina ,

The Freedmens Bureau ,

Illusions of Emancipation

Introduction

Phantoms of Freedom

On December 18, 1940, the distinguished Howard University historian Charles H. Wesley delivered a lecture commemorating the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This was seventy-five years to the day after Secretary of State William H. Seward announced that slavery was officially abolished. Wesley spoke at the newly opened Founders Library, named in honor of the thirteen men responsible for establishing the university, which Congress had chartered in 1867. That same year, the institutions namesake, Oliver Otis Howard, the Civil War hero and commissioner of the Freedmens Bureau who was often referred to as the Christian General, purchased the land where the campus stood from John A. Smith, a prominent resident of the District of Columbia. Five years earlier Smith had received $5,146.50 in compensation from the federal government for fourteen enslaved persons under the act that abolished slavery in the District of Columbia. Wesley referenced the memorial in his remarks.

Wesley focused particularly on the stylized portrayals of Lincoln and the black man who also occupied the pedestal. He noted that Balls original design, sculpted shortly after the presidents assassination, depicted the freedman kneeling in a completely passive manner, receiving his freedom at the hands of Lincoln, his liberator. In response to criticism, Wesley explained, Ball altered the model so that the slave, although kneeling, is represented as exerting his own strength to break his chains. Nearer to historical truth than the original, the final version of the statue nonetheless still failed to represent accurately the enslaved peoples role in emancipation. In the spirit of the day they commemorated, Wesley invited his audience to imagine the influence that black freedom seekers had on Lincoln and on the development of emancipation policy more generally.

One of the persons most responsible for Freedoms Memorial , William Greenleaf Eliot, a prominent St. Louis minister and foe of slavery who helped found the Western Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, offered reflections similar to Wesleys more than fifty years earlier. Acknowledging that the figures portrayed President Lincoln in the act of emancipating a negro slave, who kneels at his feet to receive the benediction, Eliot observed that the slaves hand has grasped the chain as if in the act of breaking it, suggesting that the slaves took active part in their own deliverance. Eliots comments reflected an insiders knowledge; in fact, he had convinced Ball to use the likeness, both face and figure, of Archer Alexander as the model for the freedman. Alexander had escaped from slavery in 1863, and Eliot offered him shelter and employment and even helped thwart an attempt to reenslave him. Eliot published an account of Alexanders life in 1885.

The African American artist Edmonia Lewis also portrayed emancipation through design elements and classical motifs similar to Balls in her 1867 sculpture Forever Free (see

Wesley, too, rejected the notion that freed people were passive recipients of freedom at Lincolns hand. To make the case, he drew on Frederick Douglasss remarks at the dedication of Freedoms Memorial on April 14, 1876. The veteran abolitionist strained to rebalance not just the images that Balls statue conveyed of Lincoln (the liberator) and Alexander (the liberated) but also the broadly popular stereotype that the artist had tapped into for his initial inspiration. Douglass spoke against a backdrop of the increasingly fragile Republican governments in the former Confederate states and the increasingly brazen violence against freed people everywhere. The audience included the sitting president, Ulysses S. Grant, and a host of other government officials and dignitaries as well as a number of the most distinguished black leaders in the land. The front of the memorial bore a plaque with the caption Freedoms Memorial in Grateful Memory of Abraham Lincoln, which acknowledged that the freedwoman Charlotte Scotts initial contribution of five dollars, her first earnings in freedom, had set the project in motion. Tellingly, the commemorative program altered the inscription on the plaque to read the Freedmens Memorial to Abraham Lincoln.