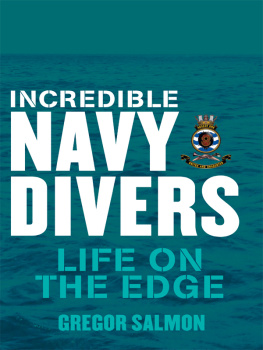

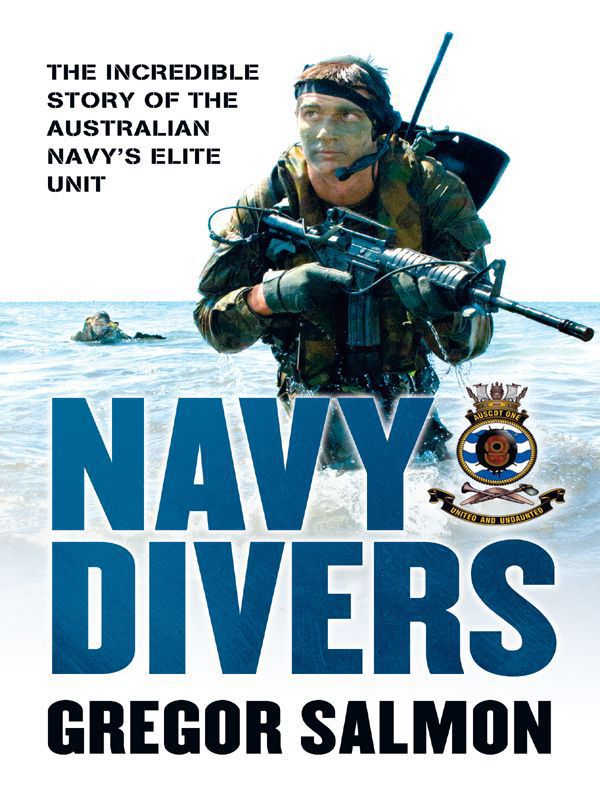

About the book

Rising out of the Second World War, the Australian clearance diver has become one of the most respected and versatile operators in the military world.

In cold, murky water, working by touch alone, they can defuse a mine powerful enough to sink a battleship. Under the burning Afghan sun, they can dismantle a Taliban roadside bomb. Welcome to the world of the Royal Australian Navy clearance divers.

Bomb and mine disposal is but one of their roles. As covert swimmers they can infi ltrate enemy waters. As boarding parties they are on the anti-piracy front line. As counterterrorist special forces they are on call 24/7. They are simply one of the best diving units in the military world.

Their story goes back to the Second World War, when Hitlers secret weapon the magnetic mine had Britain on her knees. Four extraordinary Aussies were among the brave naval volunteers who tackled Nazi mines on land and under water. The men who followed their path share the same brand of courage. From the rivers of Vietnam to the deserts of Afghanistan, navy divers have excelled under the most dire pressure, yet we know very little of their heroic deeds. Their incredible story has remained behind closed doors. Until now

CONTENTS

T WO DAYS INTO hell week, recruit Number 4 collapsed. He had just about run himself to death, his faculties so impaired youd have thought hed spent all night on the turps. Indeed, the medics treating him resembled cops overriding the will of a belligerent drunk. They stated things he didnt want to hear and he argued back, wielding his fists for emphasis. Youre off course, they told him several times, firmly and plainly. These death-knell words struck deeply into Number 4s addled brain, sounding a desperate alarm. Hed run hundreds of kilometres to prepare for this diver selection course. And, generally speaking, hed known full well what to expect ten days, maybe twelve, of torture and he was ready. Beyond fit, he was so highly conditioned as to be physically over -qualified. He could run all day. He could do 120 sit-ups, sixty push-ups and eighteen palms-out chin-ups twice the entry benchmarks without hardly breaking a sweat. Lining up with nineteen other hopefuls to begin the gruelling trial, he didnt expect to just pass; he expected to shine. Some star recruit: spat out like pie gristle on day two . It was like he had no business being there in the first place.

Those windbags down at HMAS Cerberus , the navys main training base in Western Port, Victoria, were right after all. For all the time hed been camped down there waiting and training the better part of a year had passed before he finally got to front diver selection there were older sailors from the fleet, his fitness trainers, who would talk him down. They told him he wouldnt make the cut; he didnt have the goods. The jibes were mostly harmless attempts at a reality check, but sometimes Number 4 sensed there was envy at work. He felt theyd have been pleased if hed given up on being a diver then and there. To some fleet boys, the divers were a bit uppity, a bunch of sunbaking fitness freaks who couldnt handle a boat bigger than a Zodiac. They saw themselves as a force apart, deriding regular navy for its watch-keeping and painting-and- decorating chores at sea. Divers thought they were a little bit special and perhaps deep down the fleet sailors knew there was some truth to the boast. Perhaps they werent sure whether they themselves had the right stuff to pass. And if they didnt, who was this young wannabe to believe that he did? Regardless, just on stats alone, it was an almost even-money bet that Number 4 would end up being just another diver reject, wringing his mind for clues as to what to do with his life next.

Choose your rate, choose your fate, was a common retort from would-be divers, rubbing in the fact that they could earn more, see more and do more than regular sailors if they made it, that is. You dont know what Im capable of , was Number 4s silent comeback whenever his prospects were questioned. What the hell do you know of my character? Before he joined the navy at twenty-two, Number 4 was running a steady plumbing business with his brother. Off the clock he was a promising endurance athlete aiming to represent Australia, probably in kayaking. He wasnt devoted to one sport in particular; a new event would pique his interest and he would set about trying to win it. He would train like a demon before work, turn up to the job site at seven, finish at four and then train again. He always felt knackered but it was a lifestyle he enjoyed. Then something came along and seized his imagination like nothing before: clearance diving.

Out of the blue a paratrooper mate told Number 4 that he should make a career change, and that clearance diving was the answer. What on earth was clearance diving? It sounded like some strange fringe sport, like underwater hockey. But after listening to his friend and viewing all the online videos he could find, Number 4 grew convinced that hed found his calling. He imagined action-packed times ahead, leading a life that was half trade, half adventure: diving every day; training every day; doing underwater repairs on ships with hydraulic chainsaws, drills, rivet guns and welders; conducting covert operations, demolitions and bomb disposals. Five months later he was an enlisted seaman, billeted down at Cerberus . For a year he kept fit and did all the courses the navy required of him, itching for diver selection to roll around. When that day finally arrived, he packed his bags for HMAS Penguin , the home of the Royal Australian Navy Diving School at Balmoral on Sydneys Middle Head. At last, he was going to learn to be a clearance diver. He just had to pass the screen test.

The Clearance Diver Acceptance Test, or CDAT ( see-dat ) for short, is more geared towards rejection than acceptance. Its the door bitch you must get past to enter the clearance diving world, and she has a piercing eye for weakness. CDAT is a chain of various high-intensity activities and challenges relieved by brief, irregular and altogether insufficient spells of rest. Other than the legendary Cadre Course the SASs formidable door bitch CDAT is the most exacting selection trial in the Australian armed services. The new candidates dont know much about CDAT before they begin because divers dont share many details, mostly because they are hard-pressed to remember them. Such vagueness sustains CDATs air of mystery. Whatever a recruit manages to glean, he would have taken to heart one ominous fact: diver selection is a physical and psychological ordeal bordering on torture. It has to be. Theyre not picking spin-class instructors here; theyre selecting guys who can be counted on to render a skittish mine safe, while theyre alone, under water, and staring into zero visibility. Its not everyones cup of tea.

CDAT has to dig deeper than physicality and personality. Its aim is to unearth a fundamental character trait: the right stuff. There are no in-between grades, no coaching and no backslaps. You either pass or fail, and do so purely on how you perform and conduct yourself. Participation is absolutely voluntary so, as soon as you decide you dont want to be there anymore, you just raise your hand and youre gone. You cant walk in off the street. You must enlist, complete your seamanship course, basic dive course, psych and aptitude tests, and then wait. If your application to attempt CDAT is accepted, you are sent a list of items to bring, consisting mostly of PT gear a heads-up that you are in for a flogging. Its a rare recruit who is not the least bit spooked by the CDAT mystique, and thats just the way the diving school likes it.