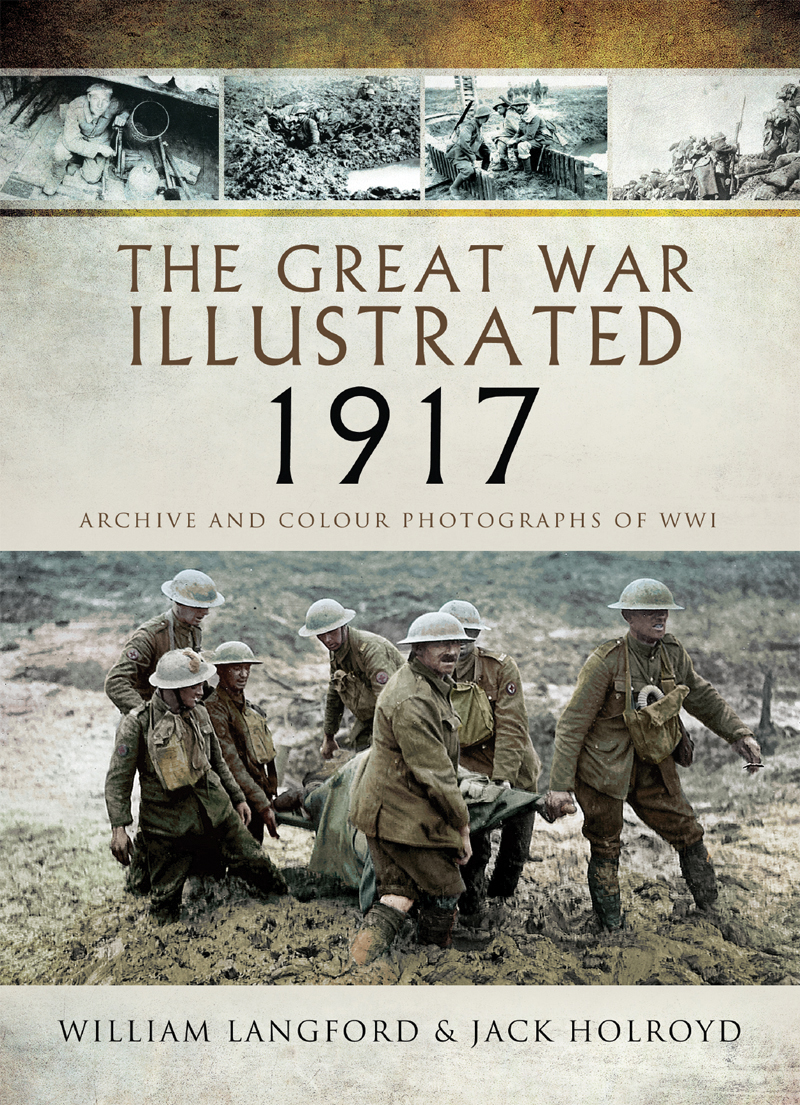

THE GREAT WAR ILLUSTRATED

1917

THE GREAT WAR ILLUSTRATED

1917

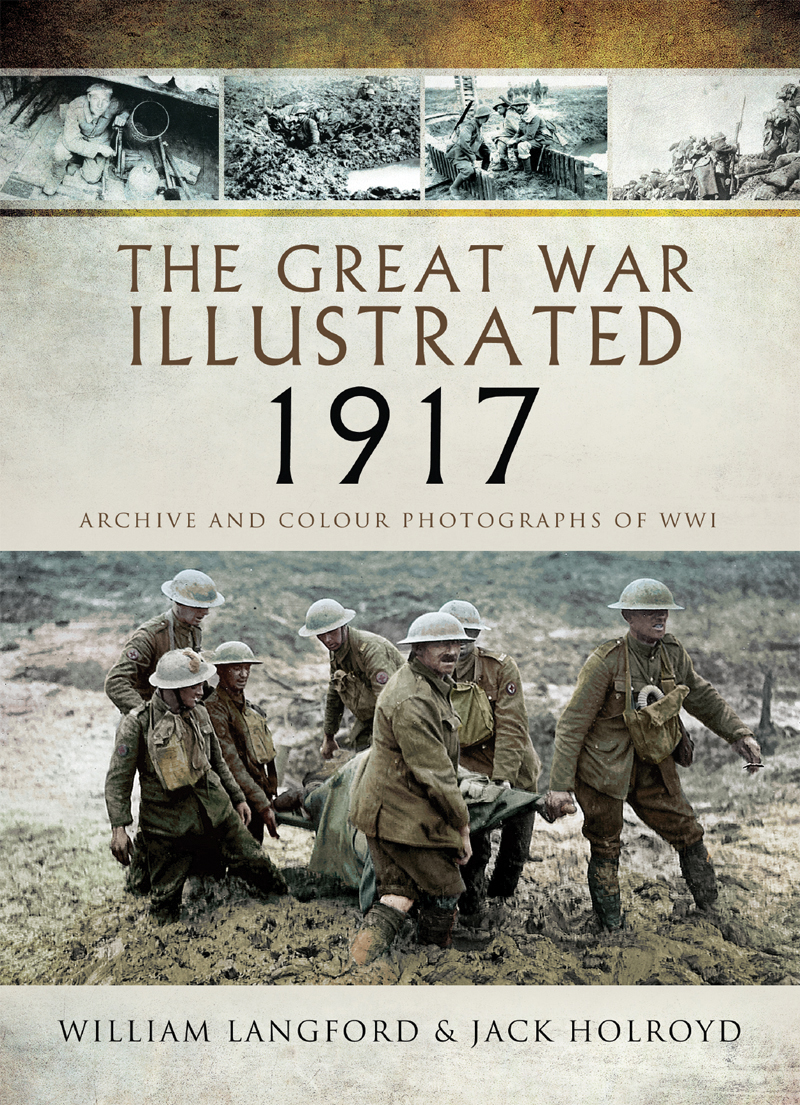

A selection of 1,000 images illustrating events at Arras; the Nivelle offensive; the battles of Messines Ridge, Passchendaele and Cambrai; the capture of Jerusalem; the air war and unrestricted submarine campaign.

William Langford & Jack Holroyd

Dedicated to the One True Sovereign

who was disregarded by the nations when, in 1914, men elected to fight among themselves on behalf of their own sovereignties

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

South Yorkshire.

S70 2AS

Copyright William Langford & Jack Holroyd 2017

ISBN 978 1 47388 161 7

eISBN 978 1 47388 163 1

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 162 4

The right of William Langford & Jack Holroyd to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Wharncliffe Local History

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, england.

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Foreword

by Nigel Cave

The Great War Illustrated 1917

In 1916 the war had been changed from the one of annihilation, the destruction of the enemys ability to resist by decisive, quick blows, to one of attrition, the grinding down of the enemys ability to continue the fight. Both sides recognised that by the summer of 1916 this was the reality of the fighting on the Western Front.

This new strategic situation was first shown at Verdun in 1916, partly in its original concept by Falkenhayn and then by the seemingly unrelenting series of attacks at vast cost in human lives over the course of the year from the offensives start in February. It was followed by the infantrymans nightmare of the Somme a much shorter battle but far more expensive in losses of men.

By the end of that battle it had become clear that the most plentiful resource, manpower, was being used up at an alarming rate. The Germans took the first initiative by shortening their line through the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line, freeing up a substantial number of divisions. New infantry tactics were widely adopted and the machinery of war machine guns, mortars, guns, vehicles, communications became increasingly plentiful and sophisticated.

The allies attempted to break the deadlock by a series of offensives the ill-fated Nivelle Offensive, Arras, Messines, Third Ypres (Passchendaele) and Cambrai. In the last of these the increasing sophistication of the offensive was illustrated by the mass use of tanks, a complex, imaginative artillery fire plan and developments in air power. But there was no breakthrough; far from it, for the German army showed not only that it was capable of fighting a brilliant defensive battle but could effectively adopt new offensive tactics, as shown by the counter offensive at Cambrai. The armies in the field were very tired and morale was low amongst all the armies as winter ended the campaigning season.

The Great War was also an economic war. The British blockade had led to the turnip winter in 1916/17 in Germany. After some hesitation, the Germans returned to a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, which threatened Britains very existence until new tactics (convoys) and equipment (for example depth charges and primitive aircraft carriers) relieved the pressure; indeed, it was the submarine threat that provided the background to Haigs thinking for an offensive in Flanders in the summer.

Two key events were to have a long term significance far greater than the war itself. In February there was a revolution in Russia; at first the country maintained its military efforts, but the October Revolution and the arrival of Lenin saw Russia seeking to get out of the war as soon as possible and an armistice was signed. Almost as momentous was the arrival of the United States on the scene in April. Although her military capability was limited (something which continued to some degree right to the end of the war), the potential was enormous; and it certainly provided the Germans with a clear idea that the war had to be ended by 1919, by which time the American armies would provide overwhelming force and be well trained in the conduct of modern, industrial warfare. The greater significance, perhaps, was the projection of American power far from her shores; apart from a hiatus in the twenties and thirties, this was to be the new world reality.

Elsewhere there was an allied disaster in Italy in November at Caporetto (and the clearest sign yet of the implementation of new tactics, producing a return to open warfare); the Ottoman Empire showed signs of crumbling around the edges (best illustrated by the fall of Jerusalem at the end of the year); even the front in Salonika began to stir from its long slumber. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was under new leadership, with the accession of Emperor and King Charles I in November; a deeply committed Catholic, he was keen to come to a just peace.

Although it might not have felt like it to the soldier in the trenches, the signs were all there to suggest that 1918 had the potential to be the most decisive year of this horrendous war.

Nigel Cave

The Taylor Picture Library

A rich source of illustrations available to authors and graphic designers today, depicting all aspects of the historic mayhem of the Great War, are to be found in the printed volumes that were published throughout the 1914-1918 period and after. Some of these appeared firstly in weekly instalments as magazines with the option of having them bound. Others began life as bound books and nearly always in sets. Famous writers of the day contributed articles and, where photographs of certain battles were unobtainable, gifted illustrators and graphic artists were commissioned and used their imaginations to depict certain events, such as the winning of a Victoria Cross, or some dreadful atrocity perpetrated by the cowardly hun.

.jpg)

As with press release photographs of the day, likewise, some captions for pictures in books should be viewed with some caution, as propaganda hype drove the writers to maintain and fuel continuing support from among the English speaking peoples for, what had been sold from the outset of hostilities to be, a worldwide crusade against evil empires.

Next page

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)