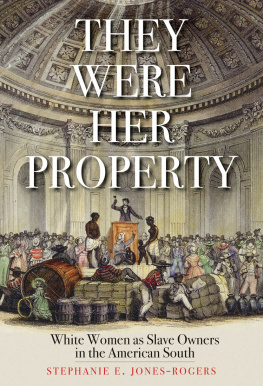

T HEY W ERE H ER P ROPERTY

Copyright 2019 by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in PostScript Electra type by IDS Infotech Limited, Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953991

ISBN 978-0-300-21866-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my foremothers, Isabella, Quessie, and Arthalia

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION : M ISTRESSES OF THE M ARKET

In 1859, after touring the antebellum South, the journalist and New York Tribune editor James Redpath attempted to explain for his readers why white southern women opposed emancipation. He believed that their sentiments were tied to a lifetime of indoctrination, reared, as they were, under the shadow of the peculiar institution. Slavery was incessantly praised and defended virtually everywhere they went, by everyone they knew, and in most of the publications they read. Their consciences, thus early perverted, were never afterwards appealed to, with the result that they saw no reason to change their views.

Redpath assumed that white southern women did not know negro slavery as it is because their society shielded them from the institutions horrific realities. Insulated by southern patriarchs, white women seldom saw slaverys most obnoxious features; they never attend auctions; never witness examinations; seldom, if ever, see the negroes lashed. More profoundly, they did not know that the inter-State trade in slaves was a gigantic commerce. Southern men revealed only the South-Side View of slavery, and if the women of the South knew slavery as it is, he was convinced, they would join in the protests against it.

Redpaths assumptions represented a commonly held patriarchal view. Yet narrative sources, legal and financial documents, and military and government correspondence make it clear that white southern women knew the most obnoxious features of slavery all too well. Slave-owning women not only witnessed the most brutal features of slavery, they took part in them, profited from them, and defended them.

Martha Gibbs was one of those women.

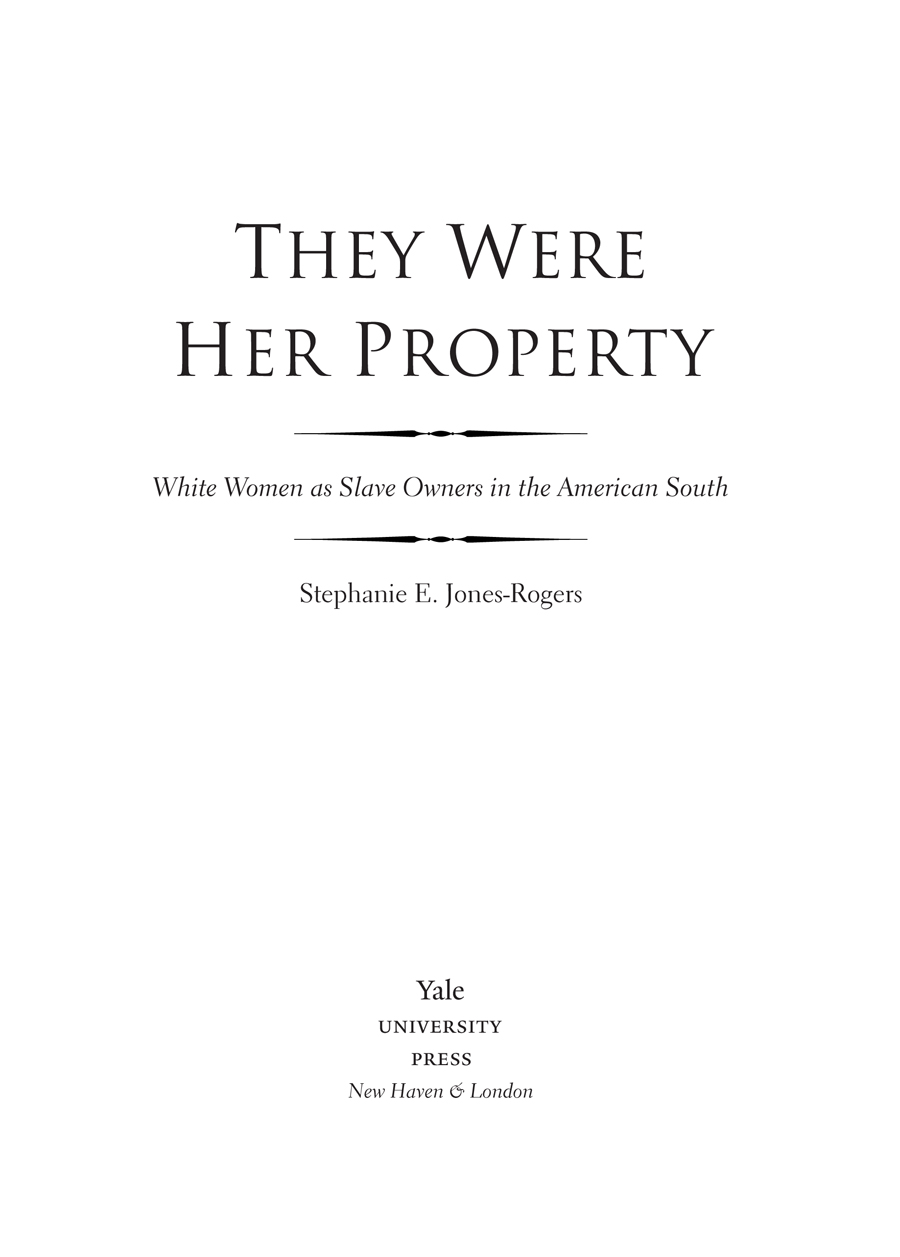

Litt Young, one of Gibbss former slaves, was interviewed as part of the Federal Writers Project (FWP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA),

In step with other slave owners throughout the South, Gibbs employed an overseer to make sure that the people she kept enslaved performed the tasks delegated to them, but she also oversaw her overseer. Almost every morning, she buckled on two guns and come out to the place to personally ensure that things were running smoothly, and she out-cussed a man when things didnt go right.

Litt Young (Federal Writers Project, United States Works Progress Administration, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

After the Confederates surrendered, and for reasons that remain unclear, local Union officers arrested Martha Gibbs and locked her up in the black foks church, where they kept her under constant guard for three days, fed her hard-tack and water, and then released her. After the soldiers set her free, Gibbs freed her slaves, but only temporarily. One day, when her husband had gone to buy corn for his livestock, she gathered up some of her slaves, ten, six-mule wagons, and one ox-cook wagon, and set off with them. They walked about 215 miles, from Vicksburg, Mississippi, to bout three miles from Marshall, Texas. She hired Irishmen guards, with rifles, to make sure that none of her freed slaves ran away during the journey, and when they stopped to rest, the guards tied the men to trees. Then, on June 19, 1866, one year after these legally free but still enslaved people made her first crop in Texas, Martha Gibbs finally let them go.

Married slave-owning women like Martha Gibbs have received scant attention in historical scholarship. Historians have acknowledged that some southern women owned slaves, but they usually focus on the wealthiest single or widowed women. When they do encounter married slave-owning women in nineteenth-century records, they generally assume that the womens legal status as wives prevented them from owning slaves in their own right. Historians rarely differentiate between married women who owned enslaved people in their own right and married women who merely lived in households in which they engaged with, managed, and benefited from the labor of the enslaved people that others owned. Historians rarely consider why slave ownership might have mattered to the women in question, to the enslaved people they owned, to slaveholding communities, to the institution of slavery, or, more broadly, to the region. Historians have neglected these women because their behaviors toward, and relationships with, their slaves do not conform to prevailing ideas about white women and slave mastery.

While it has long been recognized that southern slave owners were in the minority and that they were by no means a homogenous group, so much of what scholars know about women in the slaveholding South draws upon the diaries or letters of the most elitethose living in households that owned more than ten enslaved people. Historians have chronicled these lives, producing microhistories about an extremely small subset of an already small group of white southerners. Such studies should not be used to make generalizations about the majority of women in slaveholding communities at large; records indicate that the majority of slave owners owned ten enslaved people or less.

Scholars who examine the authority that women held over their slaves frequently focus on the womens obligatory, rather than voluntary or self-initiated, management and discipline of enslaved people. They argue that women could not be true masters of slaves. Rather, they were fictive masters. Even when they possessed the skills and the gall to manage their slaves, these historians argue, they typically did not relish their power: they did not view their activities as slave mastery, and neither did southern laws and courts. This was especially true when it came to violent forms of discipline. White women might punish enslaved people; they might even be brutal and sadistic, but they fell short of wielding a masters power. In sum, these scholars argue that slave-owning womens acts of violence differed from those of slave-owning men.

By extension, many of these scholars flatly reject the idea that white married women could adeptly manage enslaved people without the assistance of men, be they white or black, or that, aside from a few exceptional women, they could possess the acumen to do so while also effectively running plantations. Married women, they argue, begrudgingly assumed roles as deputy husbands and fictive widows when their husbands were away. When their men were present, these women happily and enthusiastically relinquished such responsibilities and exhorted their men to handle what one historian has called a mans business.

Next page