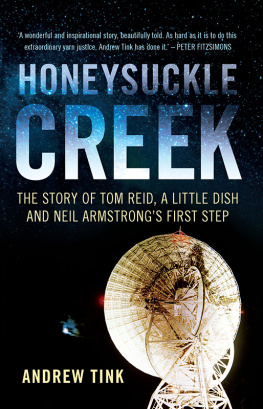

HONEYSUCKLE

CREEK

ANDREW TINK is the author of celebrated books including Lord Sydney: The life and times of Tommy Townshend, Air Disaster Canberra and Australia 19012001. His biography William Charles Wentworth won The Nib award for literature in 2010. Before taking up writing, Andrew was shadow attorney-general and shadow leader of the House in the NSW Parliament, following an earlier career as a barrister. Andrew is currently an adjunct professor at Macquarie University.

HONEYSUCKLE

CREEK

THE STORY OF TOM REID, A LITTLE DISH AND NEIL ARMSTRONGS FIRST STEP

ANDREW TINK

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Andrew Tink 2018

First published 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 9781742236087 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781742244297 (ebook)

ISBN: 9781742248721 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Lisa White

Cover image Tracking Apollo 8 in lunar orbit on Christmas Eve, 1968.

Photo by Hamish Lindsay.

Back cover image Photo of Tom Reid by Don Witten

Author photo Elizabeth Tink

Illustration opposite Based on photo by Ron Hicks

Printer Griffin Press

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

The name Honeysuckle Creek and the excellence which is implied by that name will always be remembered and recorded in the annals of manned space flight.

Christopher Columbus Kraft Jr.

Director of Flight Operations, Apollo 11

Contents

Introduction

It was a Monday morning just after 6 am. Oblivious to the mid-winter chill that would normally have kept us in bed until at least 6.30 am, my family and I had been up for a while clustered around our kitchen radio. What we heard from almost 250 000 miles away was a human voice an astronauts voice the voice of Buzz Aldrin.

Six forward lights on down two-and-a-half forty feet down two-and-a-half kicking up some dust thirty feet two-and-a-half down faint shadow four forward four forward drifting to the right a little OK four forward four forward. Drifting to the right a little. Twenty feet down a half

As Aldrins companion, Neil Armstrong, searched for a suitable place to land their lunar module, Eagle, Mission Control in Houston reminded them that they had only 30 seconds of fuel left. Would they make it? Or would they crash?

Then after what seemed like an eternity, we heard:

ALDRIN: Contact light!

ARMSTRONG: Shutdown.

ALDRIN: OK. Engine stop.

MISSION CONTROL: We copy you down, Eagle.

ARMSTRONG: Engine light is off Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!

MISSION CONTROL: Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. Youve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. Were breathing again. Thanks a lot.

According to our kitchen clock it had just gone quarter-past-six. In our different ways we were caught up in the high emotion of this moment: two men had landed on the Moon. Then, as my father was wont to do, we were hustled off to prepare for school. In my case it was a half-hour train ride from the Sydney suburb of Gordon to Town Hall, followed by a walk across Hyde Park to Sydney Grammar, an all-boys school where I was in fourth form.

Having recently turned sixteen, I was interested in girls but awkward in their company. My schoolmates and I would clog up the entry ways of the old red rattler carriages as our train snaked its way down the North Shore line. Standing nearby would be Monte girls who would get off at Milsons Point and SCEGGS girls going all the way to Darlinghurst. In our different groups we would talk at the tops of our voices, generally showing off. The girls would hitch up their skirts, just a little, while the boys would loosen their ties and effect a tousled hair look, something I could never quite pull off.

On any normal day the commuters in our carriage could not have presented a starker contrast, travelling in absolute silence and avoiding eye contact with those sitting beside them, even though they invariably travelled in the same or almost the same seats, day in and day out, year in and year out. Nearly every North Shore commuter read a paper, mostly the Sydney Morning Herald. In their cramped seats, the backs of which were uncomfortably stamped with the raised letters NSWGR, their only contact with each other was when they struggled to turn their broadsheets pages. Without the need to utter a word, some commuters had learned the art of turning their respective pages in unison to minimise any disruption. The only words any of them ever spoke on these morning commutes were directed at us. If you continue misbehaving, Ill take your names and report you to the Headmaster; Im an Old Boy you know! Angry words like that.

But on the morning of Monday, 21 July 1969, the only morning I can ever remember it being like this, every commuter in my carriage was talking: to the person in front of them, to the person behind them, to the person opposite them or to the person beside them. And there was just one question on their lips. Exactly when would Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin step out of the Eagle and begin their Moon walk, which NASA had promised would be televised live.

The Herald was reporting that the astronauts would rest for some hours before stepping outside, which in Sydney would coincide with everyones evening train ride home. Some people said they would leave work early while others tried to figure out whether, if they stayed in the city, they could watch TV screens set up in department store windows. Still others, the ones dressed in the most expensive-looking suits, quietly discussed whether to allow the television sets in their executive dining rooms to be moved into their staff canteens. Complicating all these discussions was a quote in the Herald attributed to the Apollo 11 flight director, Clifford Charlesworth: We want to stick to the flight plan. But you know how flight plans are sometimes you have to change them.