For Penny, Fin, and Rye.

And anyone who likes to eat.

CHAPTER ONE

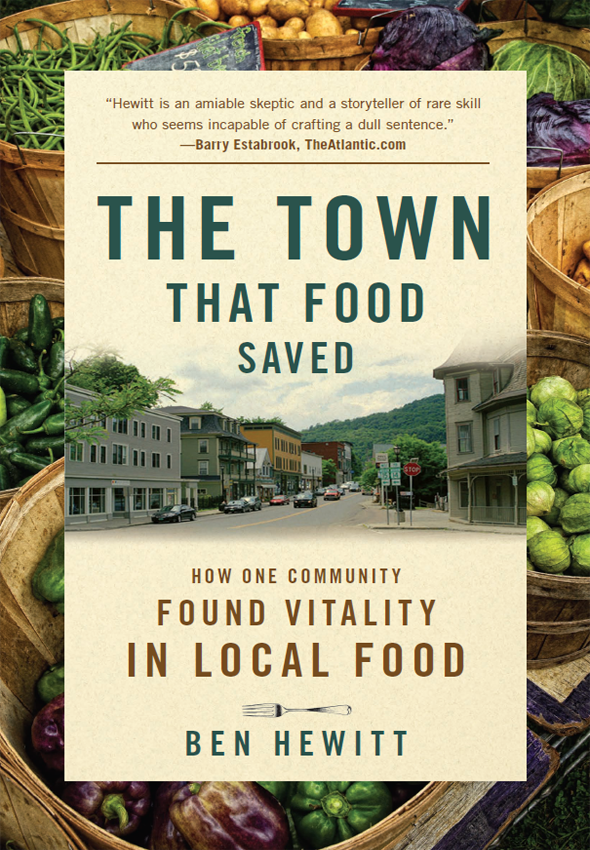

If you come into the town of Hardwick, Vermont, from the east, you come in on Route 15, weaving through a series of curves that begin as gentle sweeps and become progressively sharper until you find yourself leaning in your seat, the view through your windshield tilted just a few degrees off its axis. Thats the Lamoille River on your right, gurgling and churning over water-worn stone and gravel; it cuts a course through the center of town, and theres a nice little walking bridge that crosses the water. Its on Main Street. Its not hard to find.

On your left, the land rises steeply from the highways shoulder. Its mostly wooded, but just outside town, you can see where the hillside washed away a few years back; its since been reinforced with a massive pile of rocks, but the homes visible at its crest still look disturbingly vulnerable, as if the slightest shift will send them bouncing down the hill to splinter across the roadway.

Hardwick sits in a shallow hollow; the town and its 3,200 residents live in the shadow cast by Buffalo Mountain, which rises to nearly 3,000 feet at the southwest corner of town. Buffalo Mountain is at once craggy and lush, populated by a mix of eastern hard-woods: birch, beech, ash, and the states vaunted sugar maple. There is no road to the top, although all-terrain vehicle trails crisscross its flanks.

If you claw your way to the top of Buffalo Mountain and look out over the town, youll see how Route 15 becomes Main Street, and Main Street lasts for about a quarter-mile before it hits the towns only traffic light, which consists of a single flashing orb at the junctions of Routes 14 and 15. If you turn right, continuing on 15, youll immediately pass the former home of the Amateur Boxing Club, a garage, a gun shop, a pizza house, and a lumberyard, in that order. A bit farther out, theres a bank and a tractor-repair business. A Ford dealership. A gas station. If you go straight through the light onto 14 South, youll pass two auto-parts stores, a school, a cemetery, and a series of modest residences. In either direction, youll see how you could drive through Hardwick in two minutes or less, pushing on the accelerator as the speed limit rises again to 50 and the road unfurls across the lush Vermont countryside, drawing you in and on, helping you forget about the small town you just left behind.

Heres what you wont see: Over the past three years, this little hard-luck burg with a median income 25 percent below the state average and an unemployment rate nearly 40 percent higher has embarked on a quest to create the most comprehensive, functional, and downright vibrant local food system in North America. In the process, Hardwick, Vermont, just might prove what advocates of a decentralized food system have been saying for years: that a healthy agriculture system can be the basis of communal strength, economic vitality, food security, and general resilience in uncertain times.

Indeed, the sudden growth in Hardwicks ag infrastructure has been nothing short of explosive, with numerous food-based businesses and organizations settling in the region, seeking to become a part of the towns answer to the vexing question of what a healthy food system should look like. Vermont Soy Company. High Mowing Organic Seeds. Jasper Hill Cheese. True Yogurt. Claires Restaurant and Bar. Petes Greens. Vermont Food Venture Center. The Center for an Agricultural Economy. The Highfields Center for Composting. Honey Garden Apiaries. While a few of these enterprises have been quietly operating and growing for the past 5 to 10 years, most of them have arrived in the past 3 years, bringing nearly 100 jobs to a region that very much needed 100 jobs.

No, you wont see this from the summit of Buffalo Mountain, but you can see it along Hardwicks block-long Main Street business district, where local food-based enterprises (Claires Restaurant and Bar, the Buffalo Mountain Food Co-op, the Village Diner, the Center for an Agricultural Economy) dominate, in some cases inhabiting buildings that had long sat idle. This is not the end of it. Soon, the Vermont Food Venture Center, a shared-use commercial kitchen and product development, processing, packaging, and shipping facility, will open in Hardwick, providing a place for small-scale producers to create and distribute value-added goods made with local ingredients, saving them the massive expense and hassle of installing such a facility on their own properties. And the nonprofit Center for an Agricultural Economy recently purchased 15 acres of prime agricultural land only two blocks from downtown; plans call for establishing what the center has dubbed an Eco-Industrial Park, which will potentially include shared office space for the towns ag-based businesses, a year-round, indoor farmers market, farm and garden demonstration sites, a communal composting operation, and rental plots for budding farmers.

The recent growth in Hardwicks ag-based commerce is notable for something else: These outfits are, by and large, operated by youthful entrepreneurs possessing a surprising degree of business acumen. These are not the back-to-the-land dropouts of the regions 1970s homestead agricultural revolution, smoking joints, hand-milking goats, and bartering Grateful Dead bootlegs for bunches of warty carrots (well, okay, perhaps some of this is happening); these are, by and large, graduates of our nations elite liberal arts colleges who have sought ways to apply their six-figure educations to occupations rooted in the soil. They spend their days tending livestock, fields of lettuce, and racks of cloth-bound cheddar and their evenings convening to quaff beers and brainstorm the next step forward for this little settlement that just might be the most important food town in the United States.

If that seems like an outsize claim for a small town with a hard-bitten reputation, one need only consider the most recent outbreak of bad food news. The rise in energy and fertilizer prices has led to double- or in some cases triple-digit food inflation. In early 2008, the price of rice nearly doubled... in a single month. Milk prices are up nearly 100 percent in two years; ditto for wheat and corn prices. And with the average piece of American food traveling nearly 1,500 miles from farm to table, its likely to only get worse as finite fossil-fuel reserves continue to shrink. On average, every calorie that lands on your plate soaked up 11 calories of fossil-fuel energy as it was sown, grown, harvested, processed, and shipped. When the price of those 11 fossil-fuel calories doubles, then triples, and finally rises exponentially, the cost of that single calorie of nourishment will rise, too.

Its no great secret that over the past century, Americas food system has become increasingly industrialized and centralized. Its an economy of scale that has served us well, at least in strictly economic terms. In 1930, the average American family spent 24.2 percent of its income on food. That number has declined in every single decade since; by 2007, it had fallen to 9.8 percent. Of course, there are hidden costs in the form of health problems wrought by processed foods and an agriculture industry that has become heavily reliant on subsidies paid out of your taxes. But the fact remains: Until very recently, our food has never been cheaper. It has also never been more corrosive to our health and environment.

Next page