FROM REVIEWS OF THE FIRST EDITION

As accessible as it is scholarly. Properly set in the context of events elsewhere in the empire, it provides a straightforward account of this early episode in Scotlands story Mr Kamm informs and entertains in equal measure.

Tom Kyle in the Mail

His writing is clear and precise The author makes an excellent job of explaining and, where necessary, simplifying the tangled web of what we know, or think we know, about Roman activities between the walls and weaves this tale into the bigger picture as seen from Rome All is told in 175 enthralling pages.

Ian Keillar in History Scotland

For Eileen,

who is Scottish,

another Roman book

THE LAST FRONTIER

THE ROMAN INVASIONS OF SCOTLAND

Antony Kamm

Neil Wilson Publishing

www.nwp.co.uk

CONTENTS

LIST OF MAPS

PREFACE AND

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is a revised and updated edition, with new maps, of the book published by Tempus in 2004, since when World Heritage status has been conferred on the Antonine Wall. Its publication also coincides with the eighteenth centenary of the nal authenticated Roman invasion of Scotland, by Septimius Severus in AD 209.

In attempting to put the Roman involvement with Scotland into its historical context and in a narrative and chronological form, I have referred to the sources listed at the end of this book. I take responsibility, however, for any conclusions drawn from the evidence and for unattributed translations from classical texts.

My special thanks are due to Geoff Bailey, Dr Robert Cowan, Ian Keillar, Professor Lawrence Keppie, and Alan Senior for help with sources, to Ian Keillar, too, for information, to Andrew Wilson and Drs Jacqueline Kuijpers for resolving points of Latin, to David Levinson for thoughts on Tacitus, and to Stirling University Library for loans, interlibrary loan facilities, and document delivery services. This edition has also beneted from suggestions by Professor Anthony R. Birley, corrections to dates by Dr Gisela Negro Neto, and personal correspondence with Dr Birgitta Hoffmann.

Antony Kamm

Dollar, Clackmannanshire

February 2009

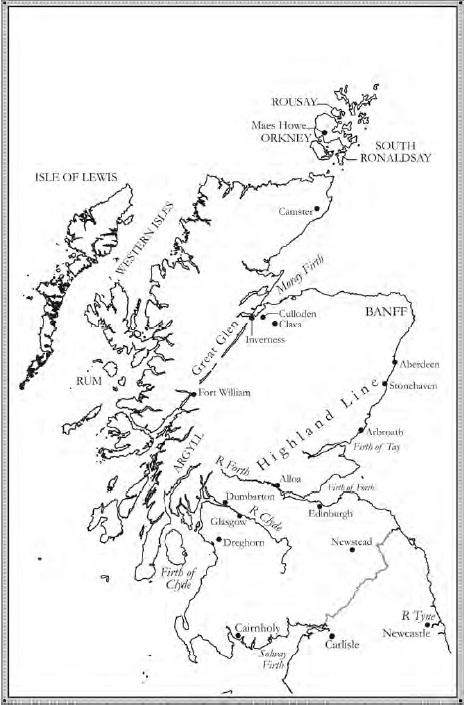

1. MODERN SCOTLAND, WITH PLACES MENTIONED IN CHAPTER 1

THE CELTS IN

SCOTLAND

Britain was still attached to the European mainland by a series of undulating valleys, when, about 18,000 years ago, the ice that covered most of Scotland began to recede. Glacial erosion carved the landscape into mountainous cliffs and corries, plateaux crossed by gullies and chasms, and, in lowland areas, rocky hills and lochs. Britain became nally separated from the mainland in about 6000 BC. By then there had been people in Scotland for some time. The first, it is now suggested, may have arrived some 14,000 years ago, well before the settlement at Kinloch, on Rum, which has been dated to 7600 BC.

In the milder climate that followed the disappearance of the ice, trees, migrating from southern Britain and from the continent, replaced the shrubs, grass, and ferns which covered much of the landscape. The rst of these was birch, around 7800 BC, followed by hazel. Northernmost Scotland and the islands around, however, retained their character of open scrub woodland for another 4,000 years. By about 5000 BC, pine and birch dominated the rest of the north west, with oak and hazel to the north east. Oak, elm, and hazel grew widely in central and lowland areas. The spreading woodlands, varying in their density according to the location, and the resources of the sea and of the lakes and rivers offered abundant opportunities for groups of hunter-gatherers, whose predecessors had followed the reindeer as the herds moved northward.

The new inhabitants were coastal people, skilled navigators of the lochs and inlets, and even of the sea itself, in dug-out canoes and skin-covered craft. They made a wide range of tools for their needs: axe-heads, scrapers, cutters, and pointed instruments from flint, hammerheads from stone, and sh-hooks and barbed heads for arrows and harpoons from bone and antler. They lived in caves or wood-framed huts; tents of dressed skins provided shelter on hunting expeditions.

A varied diet was amply available, especially to island or coastal communities. Refuse tips of the time have revealed discarded shells of more than 20 species of shellsh, as well as the bones of cod, haddock, turbot, coalsh, bream, and dog-sh, some of which could only have been caught with a line from a boat. The remains of over 30 kinds of bird have been identied, including the extinct great auk. Meat was red deer, roe deer, wild boar, and smaller animals and marine mammals, while coastal pastures provided grass and seaweed, and the forests nuts and acorns.

There is evidence of woodland management and agricultural activity, either on the part of the hunter-gatherers or of new immigrants, from about 5000 BC, when the climate became more favourable and thus sea voyages safer. Farming brought not only a radical change in lifestyle, with settled communities and new food resources, but also new economic practices and technologies. Elm trees tend to favour the better soils, and these were the rst to be cleared with stone or flint axes for agricultural land, a process assisted by an outbreak of Dutch elm disease in about 3800 BC.

The new settlers grew cereal crops, mainly wheat and barley, and kept cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep, as well as dogs. They lived for the most part in permanent settlements of timber-framed houses with turf or earth walls, from which they moved to summer grazings or shing grounds. On the Argyll coast are several sites dating to about 4000 BC which may have been processing plants for sh and shellsh. The people of the time made earthenware pots for cooking and storage. Their dead were buried in earth barrows, chambered cairns, or underground tombs constructed of stone. From one of these, a cairn with several compartments and three cells opening off the main chamber, at Isbister, South Ronaldsay, the remains have been recovered of some 340 men, women, and children, interred from about 3200 to 2800 BC. The average height of the men was about 1.70m (5ft 7in) and of the women 1.63m (5ft 4in), much the same as today. Life expectancy, however, was comparatively short; of the few who reached their 50s, most were men. Spine injuries and broken bones were commonplace, testifying to lives of heavy labour. Many of the skulls of the women were damaged by carrying loads by means of a band across the forehead.

The most astonishing traces of the early British farming culture are in the most unsuitable landscape, the northern isles of Scotland. At some point agricultural settlers sailed to Orkney and Shetland, and outlying islands, bringing with them their flocks. The bird-cherry, wild-cherry, and sloe grew there then, but otherwise the land was virtually treeless, and dominated by shrub and bare heath. In this inhospitable terrain, something more substantial than a shack was required to keep out the blasting wind and howling gales. On the coast of the tiny Orkney island of Papa Westray the remains survive of two adjoining houses with access from one to the other, occupied between about 3600 and 3100 BC. They are built from local flagstones, laid flat, with refuse packed into the walls as insulation. One has two rooms; the second may have been utilised as a storehouse or workroom, and is lined with cupboards.